The last Greek city

He was a funny one, this First Consul, thought Numerius. We are invaded by Seleucids marching north from the western landbridge over the Bosphorus. So what does the First Consul order Legio V to do in response? To march to confront them, as Numerius had requested? To hunker down and defend Byzantion? No, he orders Legio V south, across the eastern landbridge over the straits, to attack the Greeks! Numerius smiled to himself, well at least the First Consul's strategy will have the element of surprise. It surprised the hell out of me.

Numerius heart warmed at the thought of the First Consul. In truth, he admired his leader intensely and the Consul's enigmatic response to the current crisis only added to that respect. The Republic was not short of brilliant commanders, but in Numerius's estimation, she had no more interesting strategist nor more accomplished tactician than the man currently leading her.

That reflection should have cheered Numerius, but he soon lapsed back into a morose disposition. His heart was not in the current fight. It felt like the wrong enemy, in the wrong place. It was true, the Greeks had allied themselves with Seleucia and were maneouvring to take Byzantion. Hence there was a logic in the First Consul's decision to send Numerius to eradicate them. But Numerius's eyes kept looking back, over the straits, towards Maronia and the hinterland, where Seleucid armies were pouring through into Roman lands.

Numerius thought especially of Tylis, where Praetor Coruncanius was stationed with the much depleted First Field Army. Tiberius Coruncanius was a man of integrity and a fighter's spirit. Recent controversies in the Senate had brought Numerius and Tiberius together as de facto allies, although the alliance was merely an implict one of shared beliefs and outlook, rather than anything explicitly stated. And yet the thought of the general disturbed Numerius.

In his fitful rest earlier that night, Numerius had had a nightmare or was it a premonition? In his dream, Numerius's father-in-law and now nemesis in the Senate, Augustus Verginius, had led the young Tribune to an occupied bed. The imaginary Verginius had drawn back the covers of the bed, revealing the scarred remains of Tiberius Coruncanius.

"See what you have done!" Verginius had hissed.

Numerius had turned to flee in the dream, only to be accosted in a doorway by the angry spirit of Publius Pansa:

"You will stay! And you will suffer the consequences of your actions!"

Numerius shuddered. Better to be fighting real men in this waking world, than confronting such spirits in the sleeping one.

A Samartian rider approached him, his heavy armour glinting in the moonlight.

"What word of the enemy?" Numerius inquired.

"Five phalanxes, not all at full strength, led by the Pylartes of Actum" the Samartian reported. He paused and Numerius realised this was not the end. "And the Greek King, Lasthenes of Corinth, marches from Nicomedia to reinforce his heir".

Numerius attacks at night. It raises his command skill, but does not prevent the Greeks receiving reinforcements.

Numerius frowned. So the King was a night fighter too, very well. Numerius decided to deploy his men to the east, where the ground was a little steeper and furthest from Nicomedia.

Right, thought Numerius, phalanxes. I know how to fight them. Flank them with skirmishers so they can get clear shots, tie them up with our own heavy infantry and then send in the cavalry. Simple. In theory, anyway.

Numerius tries a double envelopment of the phalanxes with his light troops and cavalry. It really is a silly plan when, out of camera, the Greeks have a powerful unit of hetairoi on the loose.

So the Romans started the slow ascent of the gentle slope on which the Greeks had stationed themselves. Numerius ordered the Italian spearmen to head for the Greek general and his hetairoi stationed to the east, at the rear of the phalanxes. His own Praetoria followed closely by. Numerius was surprised to see the Greek general pull back to the rear - he's not going to retreat is he? Numerius thought. But he gave it little more thought, even when the general then advanced to take up position on the west, to the rear of the phalanxes.

Cautiously, the Romans marched up the hill, spreading out to envelope the tightly knit Greeks as a fisherman's net might snare a shoal of fish. The Romans knew these Greek phalanxes were not the slow-moving ponderous creatures of legend. The hoplites could run and lacking any missiles, Numerius thought they resembled a tightly packed coil, ready to be sprung.

Then all hell is unleashed. The phalanxes charge down the hill. But what is worse, the hetairoi barrel down the east flank, making straight for the velites.

Numerius is wrong footed and the velites pay the price.

Numerius was on the west flank, far away from the crisis point. He could only watch in horror as the resourceful velite captain hurried his men to take position behind the hastati. Some made it, many did not. Numerius signalled to the Samartian cavalry on the Roman left to counter-charge the hetairoi, but they were deterred by a small unit of levy pikemen charging straight at them. Damn, this Greek is good, cursed Numerius. He waved his hand, signalling the Sarmatians to pull back. He was determined to preserve these superb riders at all costs - running head on into charging spearmen would not be smart. The velites and the hastati would have to endure.

Numerius turned to the fight around him. His Italian spearmen, who he had originally planned to intercept the hetairoi were locked into battle with hoplites. Not a good match up, Numerius thought angrily. He ordered his Praetoria to charge the hoplites in the back, but he was distracted and the charge was botched. Damn it, can I do nothing right today? he cursed. Pull back, get back, he called to his bodyguard.

Patience, Numerius, patience. Learn from Lucius Aemilius. What he plans on the map of Europe, we must emulate here on the field of battle. The enemy is committed. Their reinforcements are far away. Our funditores and Italian skirmishers pour missiles into the rears of our enemies. Our Sarmatians and Praetoria are also on the flanks. They can take the time to line up, settle down, start at the trot, move to the canter and then ... charge!

The first cavalry charge, on the east.

And seconds later, another perfect cavalry charge, on the west.

The Sarmatians show why they are reputed to be the finest cavalry in Europe - they kill 23 hetairoi for the loss of only one of their own.

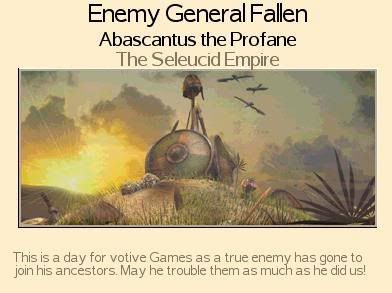

The Crown Prince of Greece, Pylartes of Actum, is among the Sarmatians' victims

And so the battle ended. With the death of their general and their flanks crushed, the Greeks hoplites broke and fled. The Sarmatians hunted them down mercilessly. The reinforcements, consisting solely of one phalanx and the Greek king with his own escort of hetairoi, hastily beat a retreat to Nicomedia.

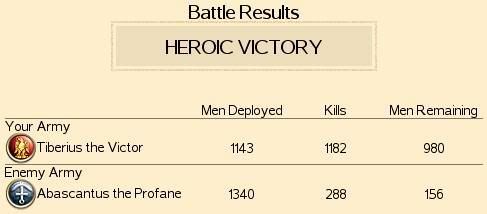

Historians will rate this battle as a heroic victory, but Numerius is not convinced. He has lost many velites and hastati, at a time when reinforcements cannot be expected. Heroic? Maybe. Smart? No.

The black mood lying over Numerius does not lift as he rides into Nicomedia the next day. This is not a battle. It is a slaughter.

The Greek King and his men await their destiny - never have men been so eager to die.

The fact that Numerius himself personally slays the Greek King leads to rejoicing among his men, but merely sinks him lower into his dark fog.

Another soul is sent to the underworld. There is no escape for mortals, even for brave Kings.

After the battle, Numerius angrily thunders around the govenor's palace, slamming into doors and aides with equal bellicosity. His timid Greek assistant looks at him uncomprehending. What has become of his normally equable master?

"Master, why this melancholy? This is a great victory! You have vanquished Greece! Your reputation grows! The men now say you are a confident attacker and a skilled infantry commander!"

Numerius snorts derisively and then stares back at the Greek angrily:

"Do you not know? Can you not guess what I have been ordered to do?!"

Numerius lets fall the message from the First Consul, setting out his grim duty. Enslave the town, man, woman and child. 5,345 subject Greeks will trek back over the straits to be sold into captivity in Roman lands. They will be stripped of their wealth and all but the barest personal possessions, bringing a meagre 1,029 denarii to the Republic.

But Numerius knows, the wealth of the town is not to be found in the pockets of its people. It lies in the buildings, the fine marble architecture of the Greeks and coffers of the many houses of state. And the temples.

Numerius Aureolus, Pontifex Maximus, stares at the list of Nicomedia's temples. They variously honour Zeus, Herackles, Dionysos, Nile and Athena. By all appearances, this was a god-fearing, civilised town. A last vestige of a great civilisation. Numerius is too well versed in history and scripture not to realise that the gods his people worship are also those of the Greeks, but merely given different names. What divine wrath does the Republic risk bringing down by this rapacious looting?

After the deed is done, the Greek aide compiles a list of the looted wealth - they have taken another 9,129 denarii, bringing the total raised by the expedition to 10,158 denarii. Numerius shakes his head at his sombre assistant.

But in truth, the destruction of bricks and mortar - even of marble - is not what most ails the young general. This Greek expedition has cost him 101 men, a fifth of his meagre force. The lives of his men mean the world to Numerius, but even more precious is what they protect - the gateway to the Republic and its first defence against the Seleucids now pouring into Europe.

What are the lives of 101 men worth? Numerius wonders.

And in his dark mood, a side of him fears he knows the answer: exactly 10,158 denarii.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks