CHAPTER II

Antiochos II Theos

263 - 230

...

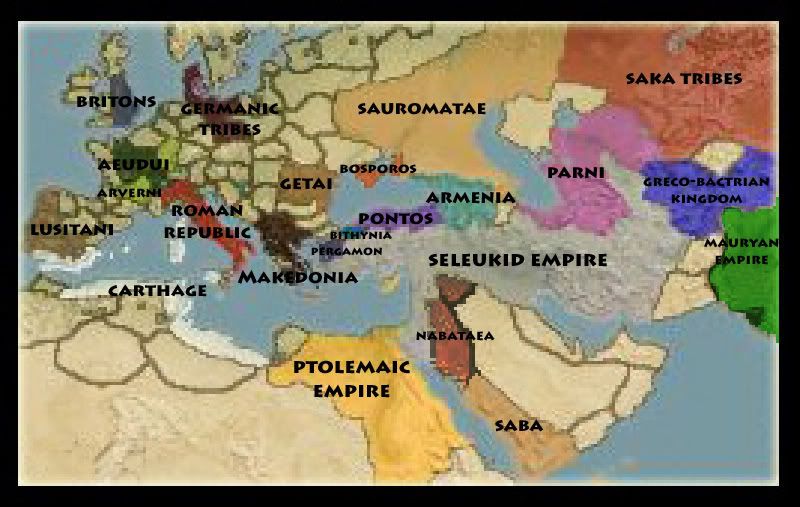

C. The Peace of Gaza (254 BCE)

With the death of Ptolemy II Philadelphos in 258 BCE, his son Euergetes inherited the Ptolemaic throne. The twenty-seven year old was immediately faced with a crisis. His uncle Meleagros had resurfaced in Paraitonion with a small army. The man who had been deposed from the Makedonian throne years earlier now laid claim to the Ptolemaic throne. Meleagros was intent on continuing the war with the Seleukids. Euergetes spent the next several years fighting his own uncle for control of the throne. By 254 BCE, Meleagros, now 61 years old, had been contained in Pselkis. Euergetes was finally free to make peace with the Seleukids.

The Peace of Gaza was to define Seleukid-Ptolemaic relations for the next twenty-five years. By its terms the Ptolemies (1) abandoned all claims to Coele-Syria (2) abandoned all claims to the southern coast of Asia Minor (3) were to pay an indemnity of 20,000 talents for the cost of the war (4) were to deliver to Antiocheia a regular supply of grain for the next ten years (5) were to sail no ships east of Kypros. For the Ptolemies the terms of the peace were devastating and ones from which they would not recover for twenty-years. For Antiochos, the war which he had not asked for brought more land and wealth to his kingdom than he could have imagined. The Seleukid kingdom was by far the most powerful kingdom in the known world.

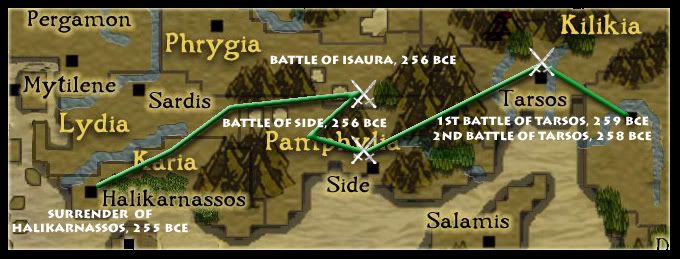

The Seleukid Empire at the end of the Second Syrian War, 254 BCE.

§2. The Nabataean War (257 BCE – 251 BCE)

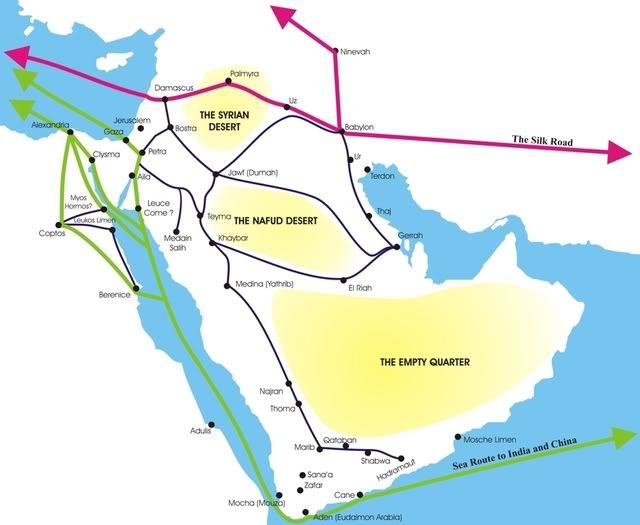

The Nabataeans were an ancient Arabic people who had migrated from the desert into the lands between the Sinai and Arabian peninsulas. By the time of Alexander’s death, the Nabataeans had made a name for themselves as one of the principle trading powers in the region. They had successfully repelled attempts by both Antigonus’ general, Athanaeus, and his son, Demetrios to invade the region. By the time of the Second Syrian War, they had expanded their influence to include not only Petra and Bostra, but Palmyra as well. They had also become a trusted ally of the Ptolemies. Their mutual cooperation led to Alexandria becoming the richest trading city in the Mediterranean world and led to the Nabataeans becoming the richest tribe in Arabia.

A map detailing the major trade routes passing through the Nabataean kingdoms.

Even prior to the signing of the Peace of Gaza, Antiochos had determined to bring these lands into his own. The Nabataeans traded in gems, balsams, Chinese silk and they had also cornered the market on bitumen, which was essential in the Egyptian embalming process. Control of these lands would not only mean command of access to and from Egypt, as well as command of the major trade routes, but possession of commodities more valuable to the Egyptians than gold. The power balance in the region would shift in favour of the Seleukids. The fact that Nabataea had supplied Ptolemy’s army at Raphia with soldiers was the pretext Antiochos needed for an invasion of these lands.

A. The Siege of Petra (257 BCE)

In 257 BCE, Antiochos marched south from Jerusalem to Petra, the capital of the Nabataean kingdom. The area his army marched through was marked by great cliffs and rugged bare rock mountains. Water was scarce in this region and the march was harsh and brutal. In early 256 BCE, Antiochos and his beleaguered army were outside the gates of Petra. Receiving word that their capital was in danger, a relief force from one of the many Nabataean forts dotting the southern border came to its aid. Battle was soon enjoined. The lightly armoured Nabataean infantry was no match for the Seleukid forces. After a day’s battle, Antiochos entered the Nabataean capital, triumphant.

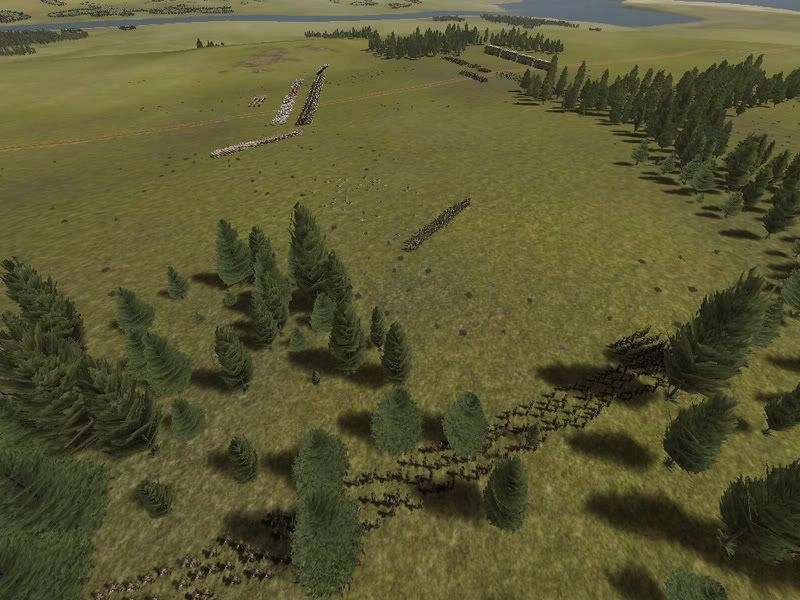

The lightly armoured Arabians clash with the well-drilled Seleukid phalanx at Petra, 257 BCE.

The lightly armoured Arabians clash with the well-drilled Seleukid phalanx at Petra, 257 BCE.

Antiochos appears to have spent the next year attending to matters in Petra, including placing a man friendly to the Seleukids, Aretus, on the Nabataean throne. Antiochos did not seek to directly control these barren lands, merely the trade and key routes passing through it. By 255 BCE, the last holdout of the Ptolemies in southern Asia Minor had submitted to Seleukid authority. And in 254 BCE, the Peace of Gaza ratified.

Antiochos next turned his attention to subduing the northern boundaries of the Nabataean kingdom, which had not submitted to him even with the fall of Petra. The planning of this northern campaign excited Antiochos for his son and heir was to join him on it. Antiochos referred to his son as Pogon (“the Bearded”) because of the beard the boy chose to wear despite its falling out of favour around the time of Alexander. The youth was by all accounts both beautiful and talented. He was nineteen years of age by this time and had spent his youth in Antioch under the tutelage of Diognetus in his father’s court.

B. The Battle of Salaminias

In 254 BCE, Antiochos and his son set out north from Damascus. A Nabataean army was harassing the trade routes along the Orontes River. Antiochos’ army met up with this force on the desert plains between Arethus and Salaminias. The ensuing battle was a lopsided affair with the Nabataeans slaughtered. Pogon appears to have given a good account of himself in this battle. Like his father, he appeared to possess the intelligence, intuition and fearlessness of a good cavalry commander.

Pogon, son of Antiochos, at the Battle of Salaminias.

Pogon, son of Antiochos, at the Battle of Salaminias.

C. The Battle of Palmyra

In late 253 BCE, Antiochos had set upon Palmyra, a vital stop for caravans crossing the Syrian desert. This burgeoning town was built on an oasis lying approximately halfway between the Mediterranean Sea in the west and the Euphrates River east, and thus helped connect the western world with the Orient. By the time of the Second Syrian War, the town had sought the protection of the Nabataeans to the south and was included in their burgeoning kingdom, though remaining largely autonomous. Once outside the town, Antiochos sent word to its leaders that should it submit without a fight, it would retain semi-autonomy under Seleukid rule. However, the leaders chose to take a stand. In a pitched battle outside the city (which had no walls at this time), the Palmyran army was crushed. The town was brought under Seleukid control.

Arabian cavalry at the Battle of Palmyra. Antiochos was so impressed with their showing that they were later incorporated into Seleukid armies.

Arabian cavalry at the Battle of Palmyra. Antiochos was so impressed with their showing that they were later incorporated into Seleukid armies.

D. The Siege of Bostra

Nabataeans and Seleukids in vicious fighting in the streets at the Siege of Bostra.

Nabataeans and Seleukids in vicious fighting in the streets at the Siege of Bostra.

In late 252 BCE, Antiochos finally turned to Bostra. The city had an impressive garrison and had taken to raids on Seleukid trade caravans and envoys along the King’s Highway south to Petra. After months of siege, the city was assaulted in early 251 BCE. The city was taken with minimal losses and the last of the Nabataean cities was in Seleukid hands. The war was over.

Aretus was recognized as a client king of the Seleukids controlling Petra and Bostra. Palmyra, for its defiance, was placed under the watch of a Seleukid governour with a military garrison protecting the key caravan stop. Antiochos now controlled the key trade routes passing through the desert and to Egypt. Though talk was made of an excursion to Arabia, of more importance was the growing Parni threat to the east.

...

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

- A Very Super Market,

- A Very Super Market,  - Machinor

- Machinor

Bookmarks