Org Mobile Site

Settings: Campaign Map - Medium (default, can't be changed in RTI, as far as I know); Battles - Hard

Prelude: A Stand for Liberty at Bunker Hill

What follows is General Warren's despatch to me following the engagement at Bunker Hill.

August 5, 1775

Our victory at Bunker Hill has lifted our countrymen to an unabashed feeling of exuberance, particularly here in New England. Those who loved liberty but feared the British Army have found new hope. Those who sat on the fence have jumped down onto the side of independence as if they were there all along. And more than a few Tories have slipped away in the dark of night, headed north with their families and possessions toward Canada.

However pleased I am that Providence smiled upon our brave soldiers that day outside of Boston, I cannot indulge in the feelings of excitement sweeping through our country. We have but two Armies, mine in the field and Col. Bellingham’s Boston garrison. The enemy are numerous, skilled and motivated after their humiliation atop Bunker Hill. Their regiments span the length of all 13 colonies, and their ships stand ready to blockade our ports and strangle our finances.

Moreover, our victory at Bunker Hill was not enough to convince the King of France to lend us aid. We shall have to do more to prove the worth and viability of our Cause.

What's more, Bunker Hill represents an escalation of our conflict into full-fledged war. The British have not only responded militarily against our small forces in the North, but also have tightened their grip on the colonies that remain under occupation, including our home of Virginia. Fortunately I anticipated such developments, and sent for Martha and our family last spring. They arrived on the first ship to sail once good weather set in and will remain in Boston until we can safely return to Virginia.

In the meantime, there is much work to do here in New England. Mr. Adams has agreed to appropriate funds for the construction of a proper Barracks and stronger Fortifications in Boston. He has also wisely convinced the Congress to provide aid for the revenue growth of the fur traders, farmers and fisheries of New England, anticipating the costs of a likely British blockade.

Having inflict’d grievous casualties on the British at Bunker Hill, they are unlikely to attempt another engagement inside New England before the winter, according to intelligence. This would be fortunate, as it would behoove our Cause for us to focus first and foremost on expanding and improving our forces into a proper Army – a daunting task that will require months of hard work.

July 4, 1777

Fireworks and feasts celebrate a year of our declared Independence, yet the rest of the colonies beyond New England continue to suffer under the heavy boot of Britain. For certain, we will soon be ready to take the fight to the enemy, who have not engag’d our forces directly, only staging raids on our frontier settlements.

The Iroquois natives have agreed to ally with us (for a not insignificant price) despite their friendly relations with Britain. This positive development, along with Mr. Revere’s progress at Yale in researching ring bayonets and other important tactical advances, gives me some hope that our planned expedition northward next year might meet with some success.

We move on Falmouth next summer, where General Howe and his army awaits.

August 8, 1778

A dear-bought victory at Falmouth, and with it Maine has her independence. After our forces had besieg'd Howe at Falmouth for six months, he attempted to break the siege by sallying forth. I was able to bring a slightly larger force northward than that fighting for Gen’l Howe, after convincing many of the minutemen who’d fought at Bunker Hill to re-enlist and training five regiments of foot at our new Barracks in Boston. Nonetheless, Howe’s troops were far more experienced.

The battle could have swung to either side’s favor throughout the clear, warm but windy day; victory hung in the balance as both lines clashed in melee. I had our regiments arrang'd in a line extending the length of a nearby hill, and the enemy started with an assault on our center and right. I ordered the right to wheel perpendicular, bracketed between our center and a small ridge, to envelop the enemy's left. Some of the British militia soon began to rout.

Despite the British having mainly militia at their disposal, it was a bloody melee and an ordeal for our newly trained line infantry out of Boston.

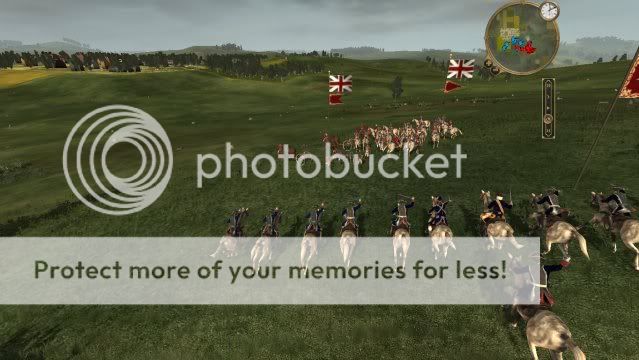

Spying General Howe’s command regiment moving forward, I ordered one of our cavalry regiments to join me in an assault, hoping to distract Howe’s infantry.

Foolishly, Howe and his outnumber’d bodyguard force met us head-on.

Horsemen on both sides fell, but Providence willed that my aide-de-camp’s sabre found General Howe’s neck within minutes. Though he served the King's cause, I regret the loss of a fellow gentleman senior officer, but truth be told it was foolhardy of him to engage rather than retreat with honour.

Upon seeing their commander fall bleeding from his horse, most of the British infantry fled. Our victory was close, and many patriots paid the ultimate price. I grieve for the brave men on both sides and wish most fervently to improve my tactics to reduce our casualties in the future. Independence will be far too bittersweet for the widows and orphans left behind in battle’s wake.

February 3, 1779

Our victory in Maine has paid great dividends for the Cause of Independence. It convinced King Louis XVI that we can defeat the British, and he agreed to support us (at a price of one-fifth of our annual revenues for three years, and with military access to our territories). The King of Spain has also agreed to trade relations, opening up their lucrative markets in the Caribbean to our goods and bringing hope of needed profits. Between this expanded trade and the continued growth of the farms and fisheries of New England, we may soon have enough revenue to field a professional Army, capable of bringing freedom to still more occupied Colonies. Mr. Revere is preparing a professional Military Syllabus at Yale to enable the efficient training of just such a professional force.

December 20, 1779

I have received a despatch from my colleague from Virginia, Mr. Richard Henry Lee, who recently surreptitiously visited our home State. He reports that Mount Vernon remains in fair condition, to my great relief, but a British colonel has taken up residence there and given his men free rein to plunder our fields, stores and distillery. He also alerted me that this Colonel offered freedom to our slaves in exchange for service in the British army. About 20 of them accepted his offer; the rest refused and were sold off, although I am told that a few managed to escape.

And it appears the British will give us little respite here in the North, either. General Henry Clinton brought a force of about 550 infantry and two regiments of horse to try to avenge the defeat and death of Gen’l Howe. Our brave troops, matching their numbers, held off the assault but at a dear cost, as half of our force perished. General Clinton perished along with nearly all his men, meaning it will be quite a while before the British have a commander with sufficient skill and forces to invade Maine again.

What’s more, the British Navy have blockaded the Port of Providence with a fleet of five ships of the line, three frigates and two brigs. It is time for the French alliance to prove its worth and keep our coasts free of British naval harassm’nt.

November 25, 1780

We have managed to defend our New England and Maine settlements reasonably well but realized we must take the fight to the enemy soon to deprive them of the means to continue harassing us. The British send their troops from Albany, New York; the settlement of Cayuga in the old Iroquois lands west of Albany; and Canada. I despatched General Ronald Court from Boston to assault the force under the command of Gen’l Charles Cornwallis at Albany. It was another close-fought thing; Gen’l Court replicated our maneouver against Gen’l Howe at Falmouth, also killing Cornwallis but losing his life in the process. The day was ours, nonetheless, and New York is free. I grieve for Gen’l Court and the 321 Patriots who perished that day; Congress has declared a week of mourning in his memory, at my urging.

The French Navy has been engaging the British fleets vigorously but has not broken the blockade of Providence. The French also have not sent a single army to our shores to aid our fights on land. With no French military aid forthcoming, Mr. Revere has redoubled his efforts to research new tactics and doctrine, now with the help of Mr. Benjamin Thompson. We shall soon be able to train our men in using the square formation to repel cavalry charges and add canister shot to the capabilities of our artillery.

The British continue to raid our settlements in Maine; if French aid is limited only to naval support, the fight for Independence shall take a very long time. It will be a battle of wills on both sides of the Atlantic more than a battle of steel and gunpowder.

But I cannot help but wonder whether we can sustain either a battle of wills or a battle of steel. The British advantage in the latter is overwhelming, particularly the longer they blockade our ports and cut off our revenues. I cannot be certain we will sustain our advantage in will, however, as the war drags on longer and the fighting moves to colonies further away from these soldiers' homes in New England and New York.

June 23, 1784

Despite the relief of the Port of Providence, under the command of Admiral de Grasse’s French fleet with a few of New York’s frigates in support, the enhanced revenues since that victory nearly three years ago have allowed us only to hold our own, and not to expand Freedom’s blessings to more colonies.

Fortunately the long stalemate has not resulted in degradation of our men's morale or good behaviour. They spend little idle time in garrison at Boston, Falmouth or Albany - having to respond quite frequently to British raids on frontier settlements near our borders with British colonies in Canada. These raids offer constant reminders that we may have brought freedom to their homes in these Northern states, but we have not yet brought security.

I ordered General Abner Haven to lead a small force to expel the British from Cayuga in the Iroquois territory; after he did so, Mr. Adams and I agreed that the territory would be more to our advantage in the hands of our Indian allies – better for them to defend it than our overstretched forces. The important thing is that it not be in British hands. The Iroquois paid handsomely to return Cayuga to their control.

I have moved back to Boston to reunite with Martha and our family and oversee the training of a new field army that I will take to Philadelphia next year. I have determined our training efforts should concentrate on the recruitment of grenadiers; all too often the British have sent numerous grenadier units into Maine, and we have known the bloody toll of these hard fighting men all too well.

I have left General Horatio Bellingham in command in Falmouth. Bellingham successfully repelled another British assault on Falmouth, killing about 1,000 British but losing half of the 1,000-strong garrison. We will not be able to do more than scrape by until we take the fight for Independence into enemy territory, into Acadia, into Canada, to secure our northern Colonies once and for all.

August 7, 1785

Finally we have put the enemy on the defensive in the North. After sustaining hundreds of casualties in another costly defense of Falmouth and another to liberate our university at Brunswick, I ordered General Bellingham to go on the offensive and invade Acadia. Conquest of Acadia would not only remove another source of British troops but also greatly boost our revenues with lucrative silver mines, fisheries and farms.

God be praised that General Bellingham found victory at Fort Nashwaak. The regional capital’s garrison was surprisingly light. If we can hold Acadia, we can limit British incursions as they can now only send armies from Montreal and Quebec. The next task for Bellingham is to block that route into our territory.

July 31, 1786

Once again I have had to bid farewell to Martha and our family in Boston. It is the safest place for them, and I must continue to lead our fight southward. Over the past two years, we have raised up a force of 850 infantry – half line infantry and half grenadiers – four regiments of horse, and four artillery units in Boston and Albany. Each year, I thank God when the re-enlistment reports come in, and the overwhelming majority choose to stay with the Army and not abandon the Cause, even as the war enters its 12th year and most of the soldiers' homes in New England, Maine and New York grow more secure from British incursions. I believe they understand the importance of Philadelphia, and know their security further North will not last long should America's largest city remain in British hands.

I rendezvous'd with General Haven in Albany three weeks ago to plan our assault on Philadelphia, and just last week, our final regiments were ready for the campaign. General Haven and I moved with those troops down the Hudson River and across the border with New Jersey. Then yesterday, we crossed the Delaware to meet the enemy at Philadelphia.

We besieged General Oliver Fowler’s garrison of 1,114 men. Knowing he outnumbered us, General Fowler sallied yesterday morning. We took up a defensive position to the south of Philadelphia, on a steep hillside between the city and the star fort.

The enemy proceeded in a long infantry line approaching the hill, and our cannons began their assault. General Fowler also sent two of his regiments of horse to our right flank in an apparent effort to get behind our lines and perhaps start an early rout. The strategem failed utterly, as our foot soldiers formed square to receive the cavalry charge and held back the horsemen long enough for General Haven’s cavalry to arrive in melee support.

When the enemy infantry arrived at the foot of the hill, Fowler sent the citizen garrison to our left flank and his grenadiers and professional foot regiments to our right. Presumably he did this to avoid diluting his force and occupy our left flank with inferior militia temporarily whilst buying time for his better troops to push through our right flank.

I ordered our grenadiers and line infantry in the center to wheel right and envelope the core of the British force.

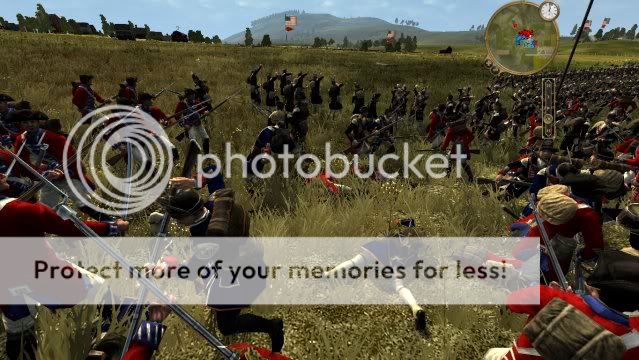

The militia and citizen garrison to our left began routing almost immediately upon arriving in range of our infantry’s musket fire. It wasn’t long before they all fled the hill, and our cavalry on the left ran them down. I order’d one of the infantry regiments from the left to move to the right to increase the fire on the British regulars on that side of the hill.

The British grenadiers and veteran foot regiments came under withering musket fire from two sides on our right, as well as cannon fire. They wisely came up through the cover of a copse of trees, but inevitably had to emerge into the hellfire of our infantry and artillery.

The pounding continued on the right side of the hill, and some British units – still trying to climb the hill - began wavering under the double-sided line of fire.

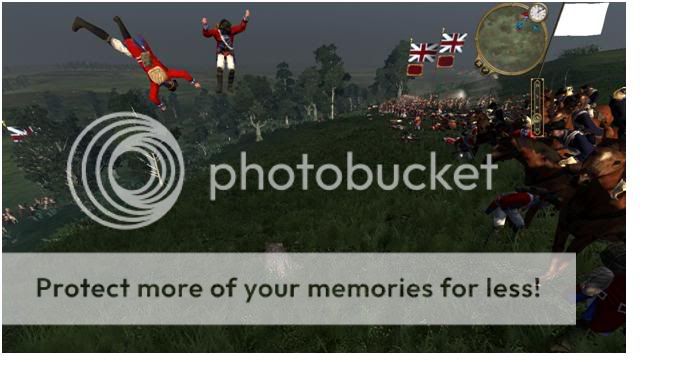

Sensing an opportunity to push the British professional infantry to join the citizen garrison in an all-out rout, I sent a regiment of horse from behind our lines in the center to charge down the hill into the British flank. The British were caught totally unawares, and our well-lather’d steeds sent several British soldiers airborne.

But with our infantry holding the perpendicular formation and continuing fire from above and to the side of the British, the wavering troops and routers had nowhere to go. Our grenadiers engaged to hurl their explosives at the remaining British holdouts, who soon joined the rest in full flight.

Our cavalry ran down the fleeing British and overwhelmed the two regiments of foot the British had kept back to protect their artillery behind their main infantry lines, far south of the hillside. The infantry quickly routed after seeing how alone they were.

Before long, the last British soldiers were swept from the field. The many routers had made it back to the star fort, so the city did not fall immediately; it held out for several more weeks. But with the casualties in the Battle of Philadelphia as lopsided as they were – 887 out of 1,114 British killed, compared to 279 out of 938 Americans – the outcome of the final British stand in Philadelphia was a foregone conclusion, and the largest city in America, with the largest British garrison, finally was liberated from British occupation, a decade after our Declaration of Independence.

August 23, 1787

To my surprise, the British did not try to re-take Philadelphia. True enough, I immediately summoned reinforcements from Albany and Boston, out of an abundence of caution to avoid losing the most important city in America so soon after winning it. But in the months since, there has been a growing sense that the British public finally is tiring of this war. Parliament repeatedly refuses to authorize funds for additional overseas reinforcements for this conflict, despite the fiercest protests of King George and Lord North. With the French pre-occupying their navy in theaters around the globe and British territories from India to Jamaica at risk, Parliament seems to want to cut Britain’s losses.

This is precisely what we have hoped for; our only real chance at victory is to outlast the British. We are insurgents; even as we make more advances toward a professional fighting force, we are still largely a band of farmers, taverners, and artisans defending our homeland from a foreign aggressor. Yes, foreign – we once thought of ourselves as Englishmen. We protested the Stamp Act and other outrages because they curtailed our God-given rights as Englishmen under English law. It became clear that the British had no intention of honoring our full rights as Englishmen, did not consider us Englishmen, would never give us our rightful representation in Parliament – and so what would become of us? We would either be slaves, or free and independent men, in a New Country, a Shining City on the Hill, as the Scriptures and our Forefathers prophesied. We are the last best hope of Liberty on the Earth.

It is my solemn responsibility to ensure our men remember that. If they remember what they are fighting for, they will do whatever it takes to repel the enemy down to the last British boots on our soil. And what does the British soldier fight for? For what does his family back in England, Scotland, Ireland – or Germany! – sacrifice? To save face for the King? Cold comfort, that will be, before much longer.

And so for as long as Parliament refuses to reinforce the British troops in America, all we need do is survive, wear them down, sap their will to fight, one battle at a time, one city at a time, one colony Liberated at a time.

Nonetheless, this month brings ill tidings from the North, one area where British will shows little sign of abating. The British sent a force of several hundred out of Quebec to ransack our iron mines in Houlton, Maine, prompting General Bellingham to pull his forces out of Acadia to repel this latest incursion.

Unfortunately Bellingham’s line infantry were no match for the British force, comprised mostly of grenadiers, and 450 out of his 570 men were killed. The British force moved from Houlton to Eastport, on the Atlantic coast. Gratefully, General William Fraith was able to move his much larger force out of Falmouth to expel the British from Eastport and kill all of their troops, but it will take time to recover from Bellingham’s defeat and re-garrison Acadia.

June 24, 1788

With stalemate ongoing in the North, I have decided to press our advantage in the South. Leaving General Haven in charge at Philadelphia, I have moved the bulk of our force, about 1,300 line infantry and grenadiers, 100 cavalry and five artillery regiments, into Maryland. We defeated the garrison of 620 British militia and Indians at Annapolis, bringing Independence south of the Mason-Dixon Line for the first time.

Happily, the proximity of Annapolis to Mount Vernon has allowed us to station a small garrison in Alexandria and liberate our home. With the nearest British troops at least three days march away in Williamsburg, I felt it safe to send for Martha and our family. After only sporadic periods together during the push to Philadelphia, we are reunited for the long haul now, and finally back home as well.

Mount Vernon still stands - Col. Edington must have fancied the riverfront view too much to burn down our house - but I cannot say the Colonel was a gracious guest during his time here. We can expect a fairly long standoff with the British force at Williamsburg; we are too far away and too strong (with our main army nearby in Maryland) for them to stage an effective assault, whilst we are not yet strong enough to attempt to confront them in Williamsburg, either. As our army rests, trains further and recruits more men, I will have more time to restore Mount Vernon and get our plantation running smoothly again. The slaves are gone, but with the Maryland and northern Virginia countryside ravaged, there are plenty of people desperate for work.

As our military fortunes have appeared to take a turn for the better, other powers have taken notice. The Dutch have now agreed to be a new trade partner, and a lucrative one at that.

But we must be vigilant against any sense of complacency. After his victory at Eastport, General Fraith has moved northward in an effort to secure our border with the Canadian colonies once and for all. Large British armies remain in Montreal and Quebec. And extending our gains southward will not be easy, either, with substantial forces continuing to occupy Williamsburg and Savannah.

July 5, 1789

Bad news from Maine cast a somber pall over the celebration of the 13th anniversary of our Independence. Colonel Tobin Robinson brought a British force of about 900 men, mostly grenadiers, southward out of Quebec, crossed the St. Lawrence River, and ambushed General Fraith and his 1,000 men near Drummondville, New France. General Fraith and 800 of his troops lost their lives, but not before inflicting grievous casualties on the enemy and leaving 556 British killed on the field.

I deeply mourn the loss of Fraith and his army; he was a talented general with hundreds of brave troops under his command, and this marks our worst loss of the war. It will take time to rebuild a force capable of securing the Northern border, and the British may well send more armies into Maine and Acadia before we have that opportunity.

August 10, 1790

In the past year, our attentions to matters of economy have truly begun to pay off. The expanding ports at Lewes and Providence and mining and agricultural improvements in all colonies have greatly boosted our revenues, which allow us to continue increasing our recruitment for our Armies with higher bonuses and salaries. Mr. Revere and his academic colleagues have been tireless in their efforts to research not only the latest military innovations but also concepts of political economy and agriculture to the great benefit of our Nation.

Consequently, we were able to build up our forces at Annapolis to 2,200 men, including more grenadiers and artillery to go with our core of regular infantry, and finally bring that army southward to liberate the rest of my home country of Virginia.

Despite this success, I have continued to be haunted by the fear that I am on borrowed time with my men's morale. They have not let me down so far. They have not become sloth or dissolute in the long periods of idle garrison in the cities we have liberated thus far. And they have mostly continued to re-enlist faithfully. Have they continued to re-enlist because of their fervent belief in Independence, and hatred of the British? Have our economic fortunes and ability to avoid large-scale bloodbaths in recent years given them a sense of security in their lives as soldiers? I posed these questions to my closest confidant, the Marquis de Lafayette.

"No, mon General," Lafayette laughed. "They do not stay for the money. Do not flatter yourself that a few years of open ports has made these men rich! And yes, they do want Independence and do despise the British, but that alone would not be enough to keep them away from their families and crops for so long. It is you, mon General. You inspire them and motivate them every day. In the harshest heat of summer, you drill right alongside them with no rest. In the darkest cold of winter, you forgo the comfort of the Officers' Headquarters to make the rounds of the campfires, showing the lowliest private that you care deeply about his well-being and morale. It is you, General Washington, and please do not forget that, or the Cause of Liberty shall be lost."

I kept Lafayette's inspiring and humbling words in mind as I positioned our forces outside Virginia's capital. We were about evenly matched in our initial assault on Williamsburg, which the arrogant British had not bothered to fortify – about 1,300 men on both sides, with my other 900 held in reserve as reinforcements. The British had mostly regular infantry and some Hessian mercenaries – not as many grenadiers as our Armies have seen in the North - but also some skirmishers known as Ferguson's riflemen, who were able to thin our ranks some, well before we were in range to return fire.

They concentrated their Hessians on their right flank, so I sent two grenadier regiments in to rout the elites with explosives. But the Hessians charged in before our grenadiers had a chance to hurl their grenades, resulting in a quick musket volley and then a close-in battle of fists and cold steel.

Though they had the advantage in numbers, the Hessians and other British regiments of foot ultimately were no match in melee with our well-trained grenadiers - corn-fed farmer's sons out of Pennsylvania's frontier who never knew a day of leisure and had the brawn and spirit to whip any Redcoat within arm's reach.

With that deed done and most of the British on our right dead or fleeing the field, our right wheeled around to enclose the British center in a kill zone. Our left still had to exchange several volleys with the enemy on the other side of the field before the British right began to break. Mr. Revere deserves a good bit of the credit for this victory, by the way, as it was one of our first opportunities to test his fire-by-rank tactical innovation. It was enormously important in being able to keep up a steady barrage of shot.

Once our left was clear, they did the same as the right and wheeled in perpendicular to the center, creating a trap for the British with our infantry enclosing them on three sides and also impeded by their own barricades once they started to flee.

Our casualties, sadly, were high; the British had erected some small battlefield earthworks that created tight spaces and vulnerabilities for our advancing infantry, and 500 out of our 1,300 fell that day. But one of the largest British armies remaining in America was annihilated, and Virginia was free.

To celebrate the liberation of my home country, I held a grand banquet for my army one week later in the Governor's residence in Williamsburg (after expelling the British governor and handing the keys over to the new Governor elected by the House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry). We had spent much of the week hunting game in the surrounding woods, and the banquet featured our finest quarry - venison, pheasant, turkey - as well as Virginia ham, bread, corn, peas, string beans, apples and squash that Martha brought down from our stores in Mount Vernon.

Of course, Mount Vernon's wine cellars and distillery took more casualties than our food stocks! Hundreds of bottles of wine and casks of ale, as well as all the 40 barrels of whiskey we had produced at our distillery in the two years since returning to Mount Vernon were utterly vanquished by our troops. I would gladly hold such feasts every year if it meant victories such as these.

June 10, 1792

Meanwhile, the stalemate continues in the North, along our border with Canada. Rather than press their advantage after the Battle of Drummondville with further incursions into Maine, the British have decided to hunker down and garrison large armies in Montreal and Quebec instead. This decision gave us the opportunity to rebuild an expeditionary force in Maine of 1,200 regular infantry and grenadiers along with 360 cavalry and four artillery regiments, all under the command of General Deacon Vere, General Fraith’s former second-in-command.

General Vere has moved his force to the south bank of the St. Lawrence River, from where he recently sent word of the construction of Ft. Sheffield on the south side of the bridge that crosses the river and meets the Montreal-Quebec road. His forces at that fort should provide a back-stop against any future incursions and form the basis for a larger Army later that will cross the St. Lawrence and remove the British threat to our Northern border for good.

And more good news from the South; the Cherokee have accepted an Alliance with us, thus removing a major concern (at least for now) for the security of our middle and Southern states as we continue to push South against the British.

From the Journal of General George Washington (1732-1811)

Commander-in-Chief, United States Army, 1775-1795

President, National Capital Planning Commission, 1795-1798

President, Constitutional Convention, 1800

1st President of the United States, 1801-1809

Commander-in-Chief, United States Army, 1775-1795

President, National Capital Planning Commission, 1795-1798

President, Constitutional Convention, 1800

1st President of the United States, 1801-1809

Prelude: A Stand for Liberty at Bunker Hill

What follows is General Warren's despatch to me following the engagement at Bunker Hill.

Originally Posted by :

Sir,

The morning broke hazy, and it was difficult to see the buildings of Boston across the Charles. We had barely finished deploying our forces before the enemy infantry began marching uphill toward us. With limited forces, we did as best we could to encircle the hilltop and avoid a flank or rear attack.

Using the hilltop buildings on our right to provide some cover, the steady fire of the minutemen and our artillery forced some early enemy routs.

To our left, the minutemen kept up a barrage of steady fire that kept the enemy at bay from the front, but we soon spied a rear attack attempt up the slope behind us. We had one regiment each of infantry and cavalry ready to engage on the rear hillside.

The fighting on the rear hillside was tough and close.

Our boys on the right kept up the pressure and the enemy made no headway on that side.

The enemy's last hope was on that rear hillside. The infantry kept up the fire to the front, preventing the enemy from pulling in reinforcements to the rear. And as the threat to the right faded, I ordered more regiments to the rear slope to overwhelm the enemy. Pretty soon our minutemen and cavalry had them enveloped, and it was over.

With the enemy now having quit Boston entirely, we shall garrison the city and await your further instructions.

Y'r servant,

Gen'l Joseph Warren

Sir,

The morning broke hazy, and it was difficult to see the buildings of Boston across the Charles. We had barely finished deploying our forces before the enemy infantry began marching uphill toward us. With limited forces, we did as best we could to encircle the hilltop and avoid a flank or rear attack.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Using the hilltop buildings on our right to provide some cover, the steady fire of the minutemen and our artillery forced some early enemy routs.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

To our left, the minutemen kept up a barrage of steady fire that kept the enemy at bay from the front, but we soon spied a rear attack attempt up the slope behind us. We had one regiment each of infantry and cavalry ready to engage on the rear hillside.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

The fighting on the rear hillside was tough and close.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Our boys on the right kept up the pressure and the enemy made no headway on that side.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

The enemy's last hope was on that rear hillside. The infantry kept up the fire to the front, preventing the enemy from pulling in reinforcements to the rear. And as the threat to the right faded, I ordered more regiments to the rear slope to overwhelm the enemy. Pretty soon our minutemen and cavalry had them enveloped, and it was over.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

With the enemy now having quit Boston entirely, we shall garrison the city and await your further instructions.

Y'r servant,

Gen'l Joseph Warren

August 5, 1775

Our victory at Bunker Hill has lifted our countrymen to an unabashed feeling of exuberance, particularly here in New England. Those who loved liberty but feared the British Army have found new hope. Those who sat on the fence have jumped down onto the side of independence as if they were there all along. And more than a few Tories have slipped away in the dark of night, headed north with their families and possessions toward Canada.

However pleased I am that Providence smiled upon our brave soldiers that day outside of Boston, I cannot indulge in the feelings of excitement sweeping through our country. We have but two Armies, mine in the field and Col. Bellingham’s Boston garrison. The enemy are numerous, skilled and motivated after their humiliation atop Bunker Hill. Their regiments span the length of all 13 colonies, and their ships stand ready to blockade our ports and strangle our finances.

Moreover, our victory at Bunker Hill was not enough to convince the King of France to lend us aid. We shall have to do more to prove the worth and viability of our Cause.

What's more, Bunker Hill represents an escalation of our conflict into full-fledged war. The British have not only responded militarily against our small forces in the North, but also have tightened their grip on the colonies that remain under occupation, including our home of Virginia. Fortunately I anticipated such developments, and sent for Martha and our family last spring. They arrived on the first ship to sail once good weather set in and will remain in Boston until we can safely return to Virginia.

In the meantime, there is much work to do here in New England. Mr. Adams has agreed to appropriate funds for the construction of a proper Barracks and stronger Fortifications in Boston. He has also wisely convinced the Congress to provide aid for the revenue growth of the fur traders, farmers and fisheries of New England, anticipating the costs of a likely British blockade.

Having inflict’d grievous casualties on the British at Bunker Hill, they are unlikely to attempt another engagement inside New England before the winter, according to intelligence. This would be fortunate, as it would behoove our Cause for us to focus first and foremost on expanding and improving our forces into a proper Army – a daunting task that will require months of hard work.

July 4, 1777

Fireworks and feasts celebrate a year of our declared Independence, yet the rest of the colonies beyond New England continue to suffer under the heavy boot of Britain. For certain, we will soon be ready to take the fight to the enemy, who have not engag’d our forces directly, only staging raids on our frontier settlements.

The Iroquois natives have agreed to ally with us (for a not insignificant price) despite their friendly relations with Britain. This positive development, along with Mr. Revere’s progress at Yale in researching ring bayonets and other important tactical advances, gives me some hope that our planned expedition northward next year might meet with some success.

We move on Falmouth next summer, where General Howe and his army awaits.

August 8, 1778

A dear-bought victory at Falmouth, and with it Maine has her independence. After our forces had besieg'd Howe at Falmouth for six months, he attempted to break the siege by sallying forth. I was able to bring a slightly larger force northward than that fighting for Gen’l Howe, after convincing many of the minutemen who’d fought at Bunker Hill to re-enlist and training five regiments of foot at our new Barracks in Boston. Nonetheless, Howe’s troops were far more experienced.

The battle could have swung to either side’s favor throughout the clear, warm but windy day; victory hung in the balance as both lines clashed in melee. I had our regiments arrang'd in a line extending the length of a nearby hill, and the enemy started with an assault on our center and right. I ordered the right to wheel perpendicular, bracketed between our center and a small ridge, to envelop the enemy's left. Some of the British militia soon began to rout.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Despite the British having mainly militia at their disposal, it was a bloody melee and an ordeal for our newly trained line infantry out of Boston.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Spying General Howe’s command regiment moving forward, I ordered one of our cavalry regiments to join me in an assault, hoping to distract Howe’s infantry.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Foolishly, Howe and his outnumber’d bodyguard force met us head-on.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Horsemen on both sides fell, but Providence willed that my aide-de-camp’s sabre found General Howe’s neck within minutes. Though he served the King's cause, I regret the loss of a fellow gentleman senior officer, but truth be told it was foolhardy of him to engage rather than retreat with honour.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Upon seeing their commander fall bleeding from his horse, most of the British infantry fled. Our victory was close, and many patriots paid the ultimate price. I grieve for the brave men on both sides and wish most fervently to improve my tactics to reduce our casualties in the future. Independence will be far too bittersweet for the widows and orphans left behind in battle’s wake.

February 3, 1779

Our victory in Maine has paid great dividends for the Cause of Independence. It convinced King Louis XVI that we can defeat the British, and he agreed to support us (at a price of one-fifth of our annual revenues for three years, and with military access to our territories). The King of Spain has also agreed to trade relations, opening up their lucrative markets in the Caribbean to our goods and bringing hope of needed profits. Between this expanded trade and the continued growth of the farms and fisheries of New England, we may soon have enough revenue to field a professional Army, capable of bringing freedom to still more occupied Colonies. Mr. Revere is preparing a professional Military Syllabus at Yale to enable the efficient training of just such a professional force.

December 20, 1779

I have received a despatch from my colleague from Virginia, Mr. Richard Henry Lee, who recently surreptitiously visited our home State. He reports that Mount Vernon remains in fair condition, to my great relief, but a British colonel has taken up residence there and given his men free rein to plunder our fields, stores and distillery. He also alerted me that this Colonel offered freedom to our slaves in exchange for service in the British army. About 20 of them accepted his offer; the rest refused and were sold off, although I am told that a few managed to escape.

And it appears the British will give us little respite here in the North, either. General Henry Clinton brought a force of about 550 infantry and two regiments of horse to try to avenge the defeat and death of Gen’l Howe. Our brave troops, matching their numbers, held off the assault but at a dear cost, as half of our force perished. General Clinton perished along with nearly all his men, meaning it will be quite a while before the British have a commander with sufficient skill and forces to invade Maine again.

What’s more, the British Navy have blockaded the Port of Providence with a fleet of five ships of the line, three frigates and two brigs. It is time for the French alliance to prove its worth and keep our coasts free of British naval harassm’nt.

November 25, 1780

We have managed to defend our New England and Maine settlements reasonably well but realized we must take the fight to the enemy soon to deprive them of the means to continue harassing us. The British send their troops from Albany, New York; the settlement of Cayuga in the old Iroquois lands west of Albany; and Canada. I despatched General Ronald Court from Boston to assault the force under the command of Gen’l Charles Cornwallis at Albany. It was another close-fought thing; Gen’l Court replicated our maneouver against Gen’l Howe at Falmouth, also killing Cornwallis but losing his life in the process. The day was ours, nonetheless, and New York is free. I grieve for Gen’l Court and the 321 Patriots who perished that day; Congress has declared a week of mourning in his memory, at my urging.

The French Navy has been engaging the British fleets vigorously but has not broken the blockade of Providence. The French also have not sent a single army to our shores to aid our fights on land. With no French military aid forthcoming, Mr. Revere has redoubled his efforts to research new tactics and doctrine, now with the help of Mr. Benjamin Thompson. We shall soon be able to train our men in using the square formation to repel cavalry charges and add canister shot to the capabilities of our artillery.

The British continue to raid our settlements in Maine; if French aid is limited only to naval support, the fight for Independence shall take a very long time. It will be a battle of wills on both sides of the Atlantic more than a battle of steel and gunpowder.

But I cannot help but wonder whether we can sustain either a battle of wills or a battle of steel. The British advantage in the latter is overwhelming, particularly the longer they blockade our ports and cut off our revenues. I cannot be certain we will sustain our advantage in will, however, as the war drags on longer and the fighting moves to colonies further away from these soldiers' homes in New England and New York.

June 23, 1784

Despite the relief of the Port of Providence, under the command of Admiral de Grasse’s French fleet with a few of New York’s frigates in support, the enhanced revenues since that victory nearly three years ago have allowed us only to hold our own, and not to expand Freedom’s blessings to more colonies.

Fortunately the long stalemate has not resulted in degradation of our men's morale or good behaviour. They spend little idle time in garrison at Boston, Falmouth or Albany - having to respond quite frequently to British raids on frontier settlements near our borders with British colonies in Canada. These raids offer constant reminders that we may have brought freedom to their homes in these Northern states, but we have not yet brought security.

I ordered General Abner Haven to lead a small force to expel the British from Cayuga in the Iroquois territory; after he did so, Mr. Adams and I agreed that the territory would be more to our advantage in the hands of our Indian allies – better for them to defend it than our overstretched forces. The important thing is that it not be in British hands. The Iroquois paid handsomely to return Cayuga to their control.

I have moved back to Boston to reunite with Martha and our family and oversee the training of a new field army that I will take to Philadelphia next year. I have determined our training efforts should concentrate on the recruitment of grenadiers; all too often the British have sent numerous grenadier units into Maine, and we have known the bloody toll of these hard fighting men all too well.

I have left General Horatio Bellingham in command in Falmouth. Bellingham successfully repelled another British assault on Falmouth, killing about 1,000 British but losing half of the 1,000-strong garrison. We will not be able to do more than scrape by until we take the fight for Independence into enemy territory, into Acadia, into Canada, to secure our northern Colonies once and for all.

August 7, 1785

Finally we have put the enemy on the defensive in the North. After sustaining hundreds of casualties in another costly defense of Falmouth and another to liberate our university at Brunswick, I ordered General Bellingham to go on the offensive and invade Acadia. Conquest of Acadia would not only remove another source of British troops but also greatly boost our revenues with lucrative silver mines, fisheries and farms.

God be praised that General Bellingham found victory at Fort Nashwaak. The regional capital’s garrison was surprisingly light. If we can hold Acadia, we can limit British incursions as they can now only send armies from Montreal and Quebec. The next task for Bellingham is to block that route into our territory.

July 31, 1786

Once again I have had to bid farewell to Martha and our family in Boston. It is the safest place for them, and I must continue to lead our fight southward. Over the past two years, we have raised up a force of 850 infantry – half line infantry and half grenadiers – four regiments of horse, and four artillery units in Boston and Albany. Each year, I thank God when the re-enlistment reports come in, and the overwhelming majority choose to stay with the Army and not abandon the Cause, even as the war enters its 12th year and most of the soldiers' homes in New England, Maine and New York grow more secure from British incursions. I believe they understand the importance of Philadelphia, and know their security further North will not last long should America's largest city remain in British hands.

I rendezvous'd with General Haven in Albany three weeks ago to plan our assault on Philadelphia, and just last week, our final regiments were ready for the campaign. General Haven and I moved with those troops down the Hudson River and across the border with New Jersey. Then yesterday, we crossed the Delaware to meet the enemy at Philadelphia.

We besieged General Oliver Fowler’s garrison of 1,114 men. Knowing he outnumbered us, General Fowler sallied yesterday morning. We took up a defensive position to the south of Philadelphia, on a steep hillside between the city and the star fort.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

The enemy proceeded in a long infantry line approaching the hill, and our cannons began their assault. General Fowler also sent two of his regiments of horse to our right flank in an apparent effort to get behind our lines and perhaps start an early rout. The strategem failed utterly, as our foot soldiers formed square to receive the cavalry charge and held back the horsemen long enough for General Haven’s cavalry to arrive in melee support.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

When the enemy infantry arrived at the foot of the hill, Fowler sent the citizen garrison to our left flank and his grenadiers and professional foot regiments to our right. Presumably he did this to avoid diluting his force and occupy our left flank with inferior militia temporarily whilst buying time for his better troops to push through our right flank.

I ordered our grenadiers and line infantry in the center to wheel right and envelope the core of the British force.

The militia and citizen garrison to our left began routing almost immediately upon arriving in range of our infantry’s musket fire. It wasn’t long before they all fled the hill, and our cavalry on the left ran them down. I order’d one of the infantry regiments from the left to move to the right to increase the fire on the British regulars on that side of the hill.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

The British grenadiers and veteran foot regiments came under withering musket fire from two sides on our right, as well as cannon fire. They wisely came up through the cover of a copse of trees, but inevitably had to emerge into the hellfire of our infantry and artillery.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

The pounding continued on the right side of the hill, and some British units – still trying to climb the hill - began wavering under the double-sided line of fire.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Sensing an opportunity to push the British professional infantry to join the citizen garrison in an all-out rout, I sent a regiment of horse from behind our lines in the center to charge down the hill into the British flank. The British were caught totally unawares, and our well-lather’d steeds sent several British soldiers airborne.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

But with our infantry holding the perpendicular formation and continuing fire from above and to the side of the British, the wavering troops and routers had nowhere to go. Our grenadiers engaged to hurl their explosives at the remaining British holdouts, who soon joined the rest in full flight.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Our cavalry ran down the fleeing British and overwhelmed the two regiments of foot the British had kept back to protect their artillery behind their main infantry lines, far south of the hillside. The infantry quickly routed after seeing how alone they were.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Before long, the last British soldiers were swept from the field. The many routers had made it back to the star fort, so the city did not fall immediately; it held out for several more weeks. But with the casualties in the Battle of Philadelphia as lopsided as they were – 887 out of 1,114 British killed, compared to 279 out of 938 Americans – the outcome of the final British stand in Philadelphia was a foregone conclusion, and the largest city in America, with the largest British garrison, finally was liberated from British occupation, a decade after our Declaration of Independence.

August 23, 1787

To my surprise, the British did not try to re-take Philadelphia. True enough, I immediately summoned reinforcements from Albany and Boston, out of an abundence of caution to avoid losing the most important city in America so soon after winning it. But in the months since, there has been a growing sense that the British public finally is tiring of this war. Parliament repeatedly refuses to authorize funds for additional overseas reinforcements for this conflict, despite the fiercest protests of King George and Lord North. With the French pre-occupying their navy in theaters around the globe and British territories from India to Jamaica at risk, Parliament seems to want to cut Britain’s losses.

This is precisely what we have hoped for; our only real chance at victory is to outlast the British. We are insurgents; even as we make more advances toward a professional fighting force, we are still largely a band of farmers, taverners, and artisans defending our homeland from a foreign aggressor. Yes, foreign – we once thought of ourselves as Englishmen. We protested the Stamp Act and other outrages because they curtailed our God-given rights as Englishmen under English law. It became clear that the British had no intention of honoring our full rights as Englishmen, did not consider us Englishmen, would never give us our rightful representation in Parliament – and so what would become of us? We would either be slaves, or free and independent men, in a New Country, a Shining City on the Hill, as the Scriptures and our Forefathers prophesied. We are the last best hope of Liberty on the Earth.

It is my solemn responsibility to ensure our men remember that. If they remember what they are fighting for, they will do whatever it takes to repel the enemy down to the last British boots on our soil. And what does the British soldier fight for? For what does his family back in England, Scotland, Ireland – or Germany! – sacrifice? To save face for the King? Cold comfort, that will be, before much longer.

And so for as long as Parliament refuses to reinforce the British troops in America, all we need do is survive, wear them down, sap their will to fight, one battle at a time, one city at a time, one colony Liberated at a time.

Nonetheless, this month brings ill tidings from the North, one area where British will shows little sign of abating. The British sent a force of several hundred out of Quebec to ransack our iron mines in Houlton, Maine, prompting General Bellingham to pull his forces out of Acadia to repel this latest incursion.

Unfortunately Bellingham’s line infantry were no match for the British force, comprised mostly of grenadiers, and 450 out of his 570 men were killed. The British force moved from Houlton to Eastport, on the Atlantic coast. Gratefully, General William Fraith was able to move his much larger force out of Falmouth to expel the British from Eastport and kill all of their troops, but it will take time to recover from Bellingham’s defeat and re-garrison Acadia.

June 24, 1788

With stalemate ongoing in the North, I have decided to press our advantage in the South. Leaving General Haven in charge at Philadelphia, I have moved the bulk of our force, about 1,300 line infantry and grenadiers, 100 cavalry and five artillery regiments, into Maryland. We defeated the garrison of 620 British militia and Indians at Annapolis, bringing Independence south of the Mason-Dixon Line for the first time.

Happily, the proximity of Annapolis to Mount Vernon has allowed us to station a small garrison in Alexandria and liberate our home. With the nearest British troops at least three days march away in Williamsburg, I felt it safe to send for Martha and our family. After only sporadic periods together during the push to Philadelphia, we are reunited for the long haul now, and finally back home as well.

Mount Vernon still stands - Col. Edington must have fancied the riverfront view too much to burn down our house - but I cannot say the Colonel was a gracious guest during his time here. We can expect a fairly long standoff with the British force at Williamsburg; we are too far away and too strong (with our main army nearby in Maryland) for them to stage an effective assault, whilst we are not yet strong enough to attempt to confront them in Williamsburg, either. As our army rests, trains further and recruits more men, I will have more time to restore Mount Vernon and get our plantation running smoothly again. The slaves are gone, but with the Maryland and northern Virginia countryside ravaged, there are plenty of people desperate for work.

As our military fortunes have appeared to take a turn for the better, other powers have taken notice. The Dutch have now agreed to be a new trade partner, and a lucrative one at that.

But we must be vigilant against any sense of complacency. After his victory at Eastport, General Fraith has moved northward in an effort to secure our border with the Canadian colonies once and for all. Large British armies remain in Montreal and Quebec. And extending our gains southward will not be easy, either, with substantial forces continuing to occupy Williamsburg and Savannah.

July 5, 1789

Bad news from Maine cast a somber pall over the celebration of the 13th anniversary of our Independence. Colonel Tobin Robinson brought a British force of about 900 men, mostly grenadiers, southward out of Quebec, crossed the St. Lawrence River, and ambushed General Fraith and his 1,000 men near Drummondville, New France. General Fraith and 800 of his troops lost their lives, but not before inflicting grievous casualties on the enemy and leaving 556 British killed on the field.

I deeply mourn the loss of Fraith and his army; he was a talented general with hundreds of brave troops under his command, and this marks our worst loss of the war. It will take time to rebuild a force capable of securing the Northern border, and the British may well send more armies into Maine and Acadia before we have that opportunity.

August 10, 1790

In the past year, our attentions to matters of economy have truly begun to pay off. The expanding ports at Lewes and Providence and mining and agricultural improvements in all colonies have greatly boosted our revenues, which allow us to continue increasing our recruitment for our Armies with higher bonuses and salaries. Mr. Revere and his academic colleagues have been tireless in their efforts to research not only the latest military innovations but also concepts of political economy and agriculture to the great benefit of our Nation.

Consequently, we were able to build up our forces at Annapolis to 2,200 men, including more grenadiers and artillery to go with our core of regular infantry, and finally bring that army southward to liberate the rest of my home country of Virginia.

Despite this success, I have continued to be haunted by the fear that I am on borrowed time with my men's morale. They have not let me down so far. They have not become sloth or dissolute in the long periods of idle garrison in the cities we have liberated thus far. And they have mostly continued to re-enlist faithfully. Have they continued to re-enlist because of their fervent belief in Independence, and hatred of the British? Have our economic fortunes and ability to avoid large-scale bloodbaths in recent years given them a sense of security in their lives as soldiers? I posed these questions to my closest confidant, the Marquis de Lafayette.

"No, mon General," Lafayette laughed. "They do not stay for the money. Do not flatter yourself that a few years of open ports has made these men rich! And yes, they do want Independence and do despise the British, but that alone would not be enough to keep them away from their families and crops for so long. It is you, mon General. You inspire them and motivate them every day. In the harshest heat of summer, you drill right alongside them with no rest. In the darkest cold of winter, you forgo the comfort of the Officers' Headquarters to make the rounds of the campfires, showing the lowliest private that you care deeply about his well-being and morale. It is you, General Washington, and please do not forget that, or the Cause of Liberty shall be lost."

I kept Lafayette's inspiring and humbling words in mind as I positioned our forces outside Virginia's capital. We were about evenly matched in our initial assault on Williamsburg, which the arrogant British had not bothered to fortify – about 1,300 men on both sides, with my other 900 held in reserve as reinforcements. The British had mostly regular infantry and some Hessian mercenaries – not as many grenadiers as our Armies have seen in the North - but also some skirmishers known as Ferguson's riflemen, who were able to thin our ranks some, well before we were in range to return fire.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

They concentrated their Hessians on their right flank, so I sent two grenadier regiments in to rout the elites with explosives. But the Hessians charged in before our grenadiers had a chance to hurl their grenades, resulting in a quick musket volley and then a close-in battle of fists and cold steel.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Though they had the advantage in numbers, the Hessians and other British regiments of foot ultimately were no match in melee with our well-trained grenadiers - corn-fed farmer's sons out of Pennsylvania's frontier who never knew a day of leisure and had the brawn and spirit to whip any Redcoat within arm's reach.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

With that deed done and most of the British on our right dead or fleeing the field, our right wheeled around to enclose the British center in a kill zone. Our left still had to exchange several volleys with the enemy on the other side of the field before the British right began to break. Mr. Revere deserves a good bit of the credit for this victory, by the way, as it was one of our first opportunities to test his fire-by-rank tactical innovation. It was enormously important in being able to keep up a steady barrage of shot.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Once our left was clear, they did the same as the right and wheeled in perpendicular to the center, creating a trap for the British with our infantry enclosing them on three sides and also impeded by their own barricades once they started to flee.

Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Our casualties, sadly, were high; the British had erected some small battlefield earthworks that created tight spaces and vulnerabilities for our advancing infantry, and 500 out of our 1,300 fell that day. But one of the largest British armies remaining in America was annihilated, and Virginia was free.

To celebrate the liberation of my home country, I held a grand banquet for my army one week later in the Governor's residence in Williamsburg (after expelling the British governor and handing the keys over to the new Governor elected by the House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry). We had spent much of the week hunting game in the surrounding woods, and the banquet featured our finest quarry - venison, pheasant, turkey - as well as Virginia ham, bread, corn, peas, string beans, apples and squash that Martha brought down from our stores in Mount Vernon.

Of course, Mount Vernon's wine cellars and distillery took more casualties than our food stocks! Hundreds of bottles of wine and casks of ale, as well as all the 40 barrels of whiskey we had produced at our distillery in the two years since returning to Mount Vernon were utterly vanquished by our troops. I would gladly hold such feasts every year if it meant victories such as these.

June 10, 1792

Meanwhile, the stalemate continues in the North, along our border with Canada. Rather than press their advantage after the Battle of Drummondville with further incursions into Maine, the British have decided to hunker down and garrison large armies in Montreal and Quebec instead. This decision gave us the opportunity to rebuild an expeditionary force in Maine of 1,200 regular infantry and grenadiers along with 360 cavalry and four artillery regiments, all under the command of General Deacon Vere, General Fraith’s former second-in-command.

General Vere has moved his force to the south bank of the St. Lawrence River, from where he recently sent word of the construction of Ft. Sheffield on the south side of the bridge that crosses the river and meets the Montreal-Quebec road. His forces at that fort should provide a back-stop against any future incursions and form the basis for a larger Army later that will cross the St. Lawrence and remove the British threat to our Northern border for good.

And more good news from the South; the Cherokee have accepted an Alliance with us, thus removing a major concern (at least for now) for the security of our middle and Southern states as we continue to push South against the British.

Updates below; also, please see above for new screenshots and story details. Thanks!

The War Moves South

September 24, 1793

It has been well over a year since I had to leave Martha once again and begin another campaign against the British. We continued South in the hopes of liberating the last of the 13 colonies – North and South Carolina and Georgia – met little resistance through the Carolina countryside, and laid siege to Charleston. We outnumbered the garrison two to one, but held out hope for a peaceful surrender. When the citizens’ supplies had finally run out, only then did the British sally forth, but against such overwhelming numbers their move was a foolish one. They should have accepted our offer of surrender right away. The ability of the British to find new ways to doom themselves through their arrogance never ceases to amaze me.

Admiral Johnson in New York has sent a fleet of two fourth-rates to the Carolina coast to reinforce protection for our all-important trade routes to the Caribbean. We are getting perilously close to pirate-infested waters, so we must remain vigilant even as the British threat seems to abate.

Meanwhile our technology advances under the direction of Mr. Revere have attracted international attention. The King of Spain has inquired about training his savants in Mr. Revere’s newest agricultural innovation – four-field crop rotation, which has accelerated the revenues of our farms most dramatically. The King of France also expressed interest in learning more about our new basic steam pump technology, which has made our iron mines in the North even more valuable. These revenues allow us to keep our military forces strong and sustain our momentum against the British.

But now my earlier fears about the sustainability of a large standing Army have begun to come true. Most of the men understand the need to liberate the Carolinas and Georgia – they stood with the Northern and Middle colonies as One to declare independence, and they are vitally important economically. But some of them are looking ahead and seeking assurances that they will finally be discharged upon the liberation of the last of the 13 states, now that we have been at war 18 long years. Some of the men who fought at Bunker Hill are still with their original regiments, while others have been relieved of duty by their sons, who were mere toddlers back then.

To keep the men focused on the task at hand and sustain our recruitment efforts, I decided to issue a proclamation regarding new land bonuses pegged to length of service. Since the states we have liberated have little new land available – possession of the land is being returned to the original owners as the British are expelled – the land bonuses will have to come from outside the 13 states. With the Iroquois and Cherokee allied to us, the lands over the Appalachian mountains are not an option. Instead, full in the confidence that General Vere will succeed in his mission across the St. Lawrence, I have promised the men land in Quebec and Upper Canada.

This, of course, has only outraged the British further, but Parliament still refuses to authorize funding for reinforcements, so there is little they can do but try desperately to hold onto their colonies, which are slipping away, one by one.

December 15, 1794

It has been an eventful year. Soon after Charleston fell, our scouts reported that British General David Woods moved a large Army of 10 militia infantry regiments, 5 native musketmen units, 3 cavalry regiments and 2 artillery units out of Savannah, Georgia, to the northwest, into the Carolina foothills of the Appalachians.

The British appear to be trying a desperate gambit – to abandon Georgia, swing back north and invade Virginia from the mountains, thus splitting the United States in two and cutting us off from our primary recruitment and training centers in Philadelphia, Albany and Boston.

I ordered General Haven to move his Army, of a similar size but better quality than Woods’ – from Williamsburg to the piedmont region of Virginia to intercept Woods. I then moved my Army out of Charleston toward Woods’ new camp in upper Carolina in an effort to ambush him.

Instead, he manages to slip past me and suddenly turn back south, taking Charleston, when I had expected him to continue north. Quickly I turned our columns back down the road to Charleston. Then another scout reported that Woods had left Savannah completely undefended. I sent two infantry regiments to Georgia’s capital, and thus Georgia was liberated – even as Carolina had come back under British occupation.

So now I write this near Charleston, with our besieging force. Woods refused my call to surrender, but the city cannot hold out long. I expect the final bloodshed in the 13 colonies to happen outside Charleston next summer.

July 18, 1795

Finally General Woods sallied forth from the outskirts of Charleston, just after dawn on the 2nd instant. Despite the early hour, the heat was already sweltering. Woods has a force of over 1,300 men – mostly militia, now that the British have lost their major Barracks in this region, along with some native mercenaries and a few cavalry and artillery units. They outnumber my 1,100 men, but I felt the long training and experience of my grenadiers, line infantry, artillery and regiments of horse would offset the difference in numbers.

We lined up to defend our position atop what passes for a hill in the Low Country, a sparsely wooded, grassy rise overlooking the townhouses and shops of the South’s largest port city. The British engaged our front, making little effort to flank save a single cavalry unit on our right who soon routed.

The tall grass offered valuable cover from the advancing British infantry, but recent heavy storms made the earth waterlogged. This aided our defense by making it even harder for the British to advance, but the marshy terrain carried with it foul, hot airs that sickened many of our troops with malaria in the days following.

The British on our left began to rout, and I ordered our left to swing down to enclose the enemy in the center. This soon resulted in a wider British retreat.

All but 200 of the British perished that day. Nearly all of the remainder died of malaria in the days following, forcing the surrender of Charleston just yesterday. Our casualties from the battle were too high, though, mainly because of the ferocity of the Indian musketmen and cavalry skirmishers. They were the last to flee the field and many fought to the death.

We lost over half our 1,100-man force, even before the malaria took its toll. My suspicion is that the Indians got word of our land incentives we started offering to the troops, figured their land was next after Canada falls. We may face even stiffer Indian resistance in the future in support of the British, and I even wonder just how strong our alliances with the Iroquois and the Cherokee are. I have sent a note to Mr. Jefferson recommending the dispatch of an envoy to the tribal chieftains, perhaps with gifts to sustain their goodwill.

And so with the fall of Charleston, and Savannah before it, the Carolinas and Georgia are liberated, and the 13 colonies that declared their Independence from Great Britain on July 4, 1776, are free, sovereign States, in name and in fact.

I must admit this milestone arrives with bittersweet feelings. Thousands of brave New Englanders, New Yorkers, Pennsylvanians, Marylanders, Virginians, Carolinians and Georgians – AMERICANS – have perished to secure the freedom and security of their countrymen, willingly paying the ultimate price for a fundamental human condition they will never get to experience.

Moreover, I once again have had to be separated from Martha and our family for nearly two years. And at 63 years of age, I regret more each passing day without their companionship, as I know those days grow more and more precious.

With the 13 colonies liberated, it is time for me to retire as Commander-in-Chief. I have promoted Colonel Silas Abbot to full General, and he will command our forces in this region. General Abner has proven more than capable of providing continued vigilance for the security of the Middle States, and up north, General Vere needs no further guidance from me to press our campaign further into Canada.

I shall inform President Adams of my decision, retire to Mount Vernon, and offer to oversee the construction of our new Capital across the river from my home.

November 28, 1798

Even in my retired state, I still receive letters from commanders in the field, keeping me up to date on events and seeking my counsel. Earlier in the fall, General Vere wrote requesting my advice on his invasion of Canada. He wondered whether it would be better to assault Quebec and Montreal simultaneously or sequentially. His Army was the far superior in number and quantity of either city’s garrison, but might be evenly matched should both forces combine to attack his unified force. I advised him to send General Harvey Alden with half of his force to assault Quebec, whilst Vere, with more experience, should attack Montreal in case the enemy call in reinforcements from the frontier.

That is precisely what happened, according to today’s letter from General Vere. Vere had 1,100 men besieging Montreal when the garrison of 700 British and native forces sallied, supported by 1,000 British grenadiers, native musketmen and cavalry from the Canadian wilderness under the command of General Benjamin Thompson.

Fortunately, the British felt they could not wait for all the reinforcements to arrive before beginning their assault. After Vere arranged his troops along a gentle slope on the outskirts of Montreal – with his right flank dug into a heavily wooded area in the highest part of the hill – the enemy began their attack with a cavalry strike on the right. The infantry formed square to repel the cavalry charge. Meanwhile, Vere called in cavalry support from the center, and the infantry and artillery on the left wheeled forward to form a V with the right flank.

As the Indian cavalry started to peel back from the infantry square, Vere’s cavalry charged.

That unit routed, but the right flank remained quite busy with the other cavalry and some Hessian units the British had sent toward the woods. Meanwhile, the British infantry caught up and engaged the center, but soon were entrapted between the left and the center in the middle of the “V” formation.

Vere’s grenadiers near the center of the “V” hurled their explosives at the British grenadiers and other infantry, prompting most of the British infantry in the center to rout soon after.

Vere had also sent grenadiers to the right, and they launched their weapons at the Hessians in the woods …

… prompting them to rout as well.

But those routs were soon followed by the first wave of British reinforcements.

The fighting in the woods was close and chaotic. Vere’s men were quite tired from having fought off the first wave, but the British reinforcements were even more tired from having to march a long distance to join the battle.

The difference in fatigue turned the tide, because it made all the difference when Vere and his other cavalry units charged the grenadiers in the flank. When the other British saw the grenadiers routed and were cut down by our cavalry, it didn’t take long for their morale to break as well.

Nonetheless, few American regiments were left standing after such a long, terrible assault. General Vere lost 700 out of his 1,100 men. All but 150 of the 1,700 British troops deployed were killed.

With such a depleted force, General Vere could not assault Montreal right away. He expects the city to hold out until next summer and then surrender.

May 30, 1799

Received a letter from General Vere today informing me that Montreal has fallen sooner than expected. What’s more, he reports that the Quebec garrison failed in their attempt to sally against General Alden. Alden was dug in with extensive earthworks on a steep hillside near the Plains of Abraham, making it impossible for the British to dislodge him. They did concentrate their assault on the right side, however, resulting in grievous casualties to the regiments deployed there. Three hundred out of the 1,000 troops under General Alden perished as Quebec fell.

I’m also receiving scores of letters from troops who served under my command, thanking me and wishing me well. I’m sure many of them are also happy about the fall of Quebec and Montreal because of the land bounties. I have no doubt enough of them would have fought on without the promise of land, and could not have blamed those who decided they had to end their service because of years of neglect of their farms and families. The land bounties were the least we could do for these brave patriots; moreover, British control of the St. Lawrence River valley would have endangered our security for many more years to come.

Good news arrives from far in the South as well. We have wrested Florida, along with her prosperous ports and plantations, from British control with General Abbot’s victory at St. Augustine. He brought about 1,300 grenadiers, line infantry, cavalry and artillery from Charleston to face the 1,400 British line infantry, grenadiers and Indian cavalry under General Engelbert Sutton.

In a sharp contrast to the terrain advantages General Alden enjoyed in Quebec, Florida is almost completely flat. General Abbot assembled his troops on a slight rise overlooking the town, but the British assault did not face the obstacle of marching up a steep hill to attack them.

General Abbot built earthworks and barricades …

But they proved useless for several regiments, who had to leave their initial deployment area to the left to relieve their fellow soldiers in the center, who faced the bulk of the British assault. Abbot ordered the regiments from the left to envelope the British in a “V” shape with the center similar to Vere’s tactic in Montreal. At the point of the “V” was an artillery unit, shelling the British infantry with canister shot.

As in South Carolina, the men used the cover of tall grass to their advantage as the British approach. Fortunately, Florida was suffering from a drought, so there was no foul, wet air to infect them with disease.

Abbot’s strategy almost failed. Some British regiments were able to get behind the lines of Abbot’s regiments moving in from the left before they were able to get in position to form the left side of the “V.”

However, some of the regiments moving in from the left were grenadiers, and they were able to turn and launch their grenades at the British foot soldiers before they could position themselves for a flank attack.

The would-be flankers routed, as did the rest of the British infantry soon thereafter, trapped in the middle of the fully assembled “V” formation.