“He conquers who conquers himself”

Latin Proverb quotes

Macedonicus

A history of Rome, by Prof Alfred Kennard, 2002 New York

The consulship of Metellus was characterized by the lex orata, an anti luxury law that limited the wealth people could own without taxation. The law was well intended, but never actually used. Nevertheless it marked Metellus as a guardian of morality and as a fighter against corruption. Metellus tried to make a good example and used his own money on public buildings and infrastructure. He assigned his childhood friend Manius Claudius Sabinus during his consulship to build a network of roads in Spain, needed for the military and trade. Metellus always was interested in architecture and later in his life he wrote a book called “de architectura” in which he describes his work on roads in Sicily and the improvement of the existing Aqueducts in Rome.

After his consulship Metellus remained an important figure in the Senate and his opinion on political matters remained heavy, even with different consuls.

In 164 BC Spurius Cornelius Sulla died peacefully in his mansion with old age. The popular victor over the Celts and Carthaginians was mourned by a 2 week festival in Rome. Metellus publicly honoured his great skills in battle and the name Sulla remained valued, despite the fact that Metellus exiled one of his sons.

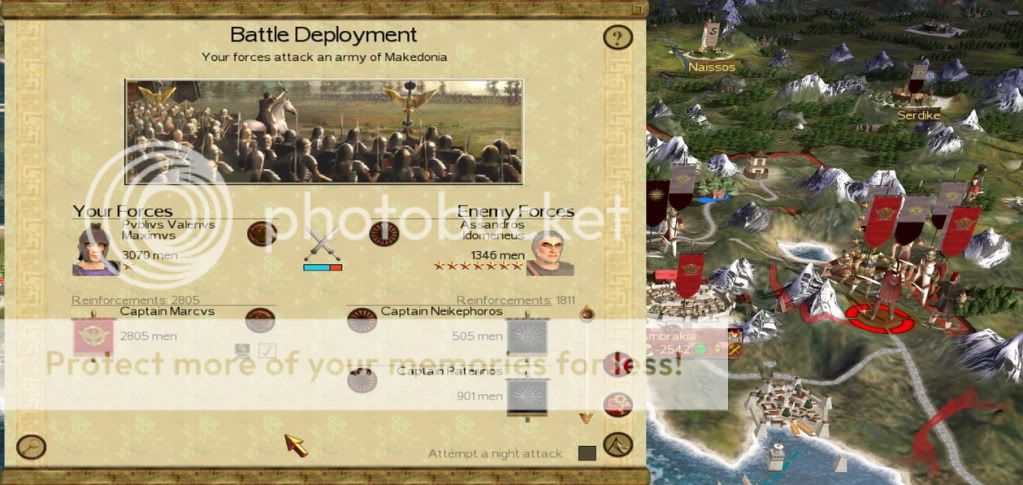

The next year, in fall of 163 BC, Alexander IV Idomeneus invaded Epirus once again. The Roman legion retreated to the south-west since the Macedonian army was too large. It had about 45.000 men, 25.000 attacking from the north and 20.000 from the south. The most important factor was that Alexander IV had reformed his army since the last defeat against the Romans in 176 BC. Now his Phalanx was filled with Illyrians to make up the low numbers of Macedonians in the army and the equipment was improved as well.

The Romans elected a Publius Valerius Maximus as of the two consuls, a disimpassioned and unimposing Senator with promising military skills. Already in February of 162 he sailed with a small fleet and an additional legion to Greece.

The Macedonians sent their large fleet under their admiral Astrabakos to prevent the Romans from landing troops. But Astrabakos was halted by rough days at the sea and arrived to late to prevent Maximus to land. Nevertheless it came to a sea battle at the gulf of Avlona (modern day Vlorë in Albania) where about 150 modern warships destroyed a great portion of the 50 Roman ships. For the time being, the Romans didn’t have an adequate fleet, so the superiority of the see remained with the Macedonians. Nevertheless Maximus landed his troops successful in Greece, ready to attack Alexander IV.

Two legions were situated in the south ready to attack Alexander’s forces, naturally Maximus task would have been to engage the larger northern army. But Maximus wanted to risk a strategic move to end the war quickly by concentrating all his troops to the south. Alexander was caught off guard and retreated east to the mountains, but had to face Maximus at the battle of Milea in the fall of 162 BC.

Silanos – Historiai

(written about 130 BC)

Book X

[…] Alexander IV was indeed a strange yet fascinating man. Now being in his 60ies, he was still strong and vivid in everything he did. On the one side he was a brilliant political leader that united all the Macedonian and Greek factions with passionate speeches, he was inclined to philosophy but never lost sight for what was possible. On other side, however, he was that he was obsessed with his eponym Alexander the Great. The tale of a 30 year old young man conquering the whole Persian Empire fascinated him since he was young. It was his believe, that he had the spirit of Alexander the Great in him. Needless to say, the new Persian Empire was seen as the Roman Republic, who in his eyes sought to conquer all of Greece and Macedonia. By attacking the Romans he hoped to conquer all of Italy, Illyrian and Spain, creating a new Alexandrian Empire. After his defeat against Scipio he reformed his armies, filling ranks with Illyrians and Barbarians.

When Maximus attacked him with a large army he was surprised by the bold move of the Roman, as the Macedonians and the Greeks saw the Romans as untalented tactical leaders. Alexander used the terrain for his advantage, trying to split the legions apart, fighting one legion at a time. A victory at the valley of Milea could change everything for the Macedonian king.

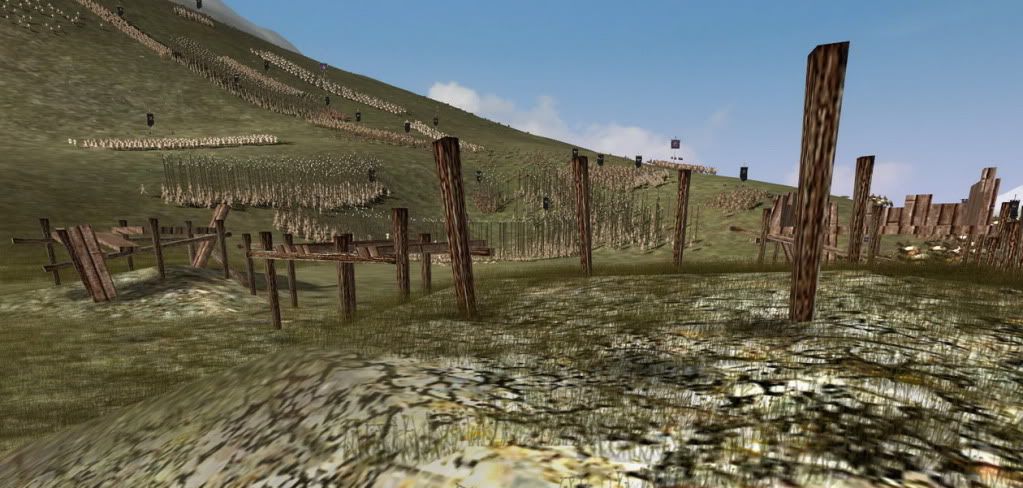

The battle was fought on the hill slopes on the left flank of the Romans

Roman skirmisher (Velites) marching to position

Milea itself was an old settlement destroyed long ago by invading Barbarians, the ruins were still a landmark when the bold Maximus attacked Alexander.

The Maceondian army consisted of a good deal of Thracian mercaneries.

Both leaders knew that the whole battle was to be decided by the slopes of the local hill. The best troops on both sides fought here for the control of the battle.

Roman cavalry engaging Macedonian heavy skirmisher on the hill slopes.

The fighting on the slopes were difficult and exhausting for both sides.

Both sides fought bravely and determined to win. Unfortunately for the Macedonians Alexander was stabbed during the battle in the stomach by a Roman equestrian, harming the Macedonian king. Alexander had to retreat from the battlefield to his camp since he was bleeding terribly. But unlike the battle of Berora against Scipio Alexander’s troops were disciplined and fought on for the cause of their king.

Macedonian heavy infrantry regrouping on the battle field.

Roman light Infrantry (Hastati) fighting though a Phalanx.

Alexander was successful in splitting Maximus’ troops apart since the reinforcements did not arrive to the battlefield that day. Nevertheless the wounded king was unable to lead his men from the bed of his camp. Maximus eventually won the flanks on the slope tearing the Macedonian Phalanx apart and thus wining the battle. When the disorientated Macedonians started to flee, the Roman cavalry hunted down many fleeing soldiers. When the surviving troops came back to the camp they were informed by the Greek doctors that Alexander was lethally and bled to death. This was the day the last Macedonian king died.

Macedonians fleeing from the enemy.

A history of Rome, by Prof Alfred Kennard, 2002 New York

After the victory Maximus returned to Ambrakia, the rest of the northern army retreated to the Borders of Macedonia. Maximus spent the winter there, reorganising his troops. He sent word to the senate in Rome what to do with Macedoni. The answer came not from Rome but from a nephew of Alexander who was about to proclaim himself king: Lysanias Saneus.

For the Romans the position was clear, the Macedonians had betrayed them multiple times and not followed treaties, furthermore Alexander had illegally attacked the Achaean league prior to the war. For the Maximus the Macedonians could not be trusted anymore and had to be defeated. The following spring in 161 BC Maximus marched on the undefended city of Pella, the capital of Macedonia. Maximus made an offer to the inhabitants that he would not kill a single human being if they submitted to the Romans. The inhabitants of Pella agreed and were eventually sold to slavery. Maximus order his soldiers to plunder and burn down the city as a sign against the Macedonians. In the summer Maximus marched to the south hoping to face Lysanias Saneus in battle.

In the battle of Demetrias Maximus faced a strong Macedonian army.

Reformed Macedonian Phalanx fighting against the Roman legion

Lysanias being killed in battle.

But Lysanias was too young and too inexperienced as a military leader. He lost his life and the battle as well. In the fall of 161 Maximus entered the city of Athens, making him the conqueror of one of the most prestigious city of antiquity. Maximus was welcomed as the liberator of Macedonian tyranny, and even though he did not like the Greeks at all he took part in a public welcoming.

News quickly spread in Rome that the ancient city of Athens was in Roman hands – the popularity of Maximus was rising and for the people it looked like the Macedonians were already defeated. But a large Macedonian army was still located at Serdike (modern-day Sofia) threatening to conquer back the territory. It wasn’t until 159 BC that Maximus had his troops ready to attack to the north. There he met the military leader of the army Ptolemas Libethrios at the battle of Astibos.

Thracians made up most of the army of Ptolemas

Hastati waiting for the enemy attack.

A centurion charging with his maniple against the Macedonians.

Tense fighting on both sides.

The aftermath.

Maximus won the third and last battle in his campaign by using his huge amount of cavalry to outflank the enemy and encircle the Macedonian Phalanx.

There was no one opposing Roman conquest in Macedonia anymore, Alexander IV was dead and all important cities in Roman hand. In late 159 Maximus declared victory over the Macedonians and returned to Rome in 158. His return to the city was celebrated with a large triumph. The senate was so pleased with Maximus’ success in Macedonia that they rewarded him with the title of Macedonicus to his surname. His full name was now Publius Valerius Maximus Macedonicus.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks