Spoiler Alert, click show to read:

Manuscript translated by Prof. M___ G______ of G______ University:

This is the translation of a recently found manuscript written by an hitherto unknown Greek writer named H____, dating from the early first century CE. The manuscript has not been preserved fully and only passages remain. I will give some short historical background information on the passages where necessary.

For the convenience of the reader I have adapted the dating from the Olympiad dating to our own year numbering system. All dates are BC, unless mentioned otherwise. For the same reason I have translated this manuscript using the past tense were the writer used the historical praesens. Any other remarks, such as illustrations, will be placed between brackets or under the text.

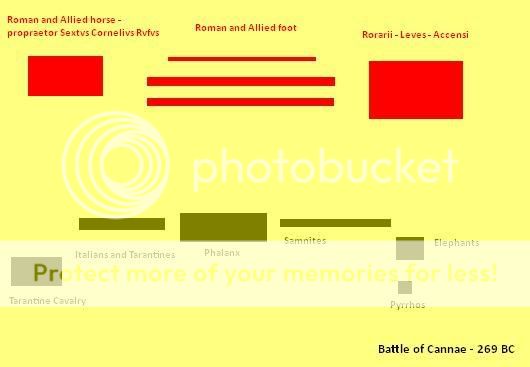

Map of Italy, Illyria, Epeiros, Mecedonia and Hellas:

Outnumbered

Book I, 5-19.

Background:

After beating Antigonos II Gonatas of Makedonia, Pyrrhos of Epeiros took possession of Pella, of Aigai – the ancient royal capital, where the tombs of the Makedonian kings lay – and of Makedonian kingship.

However, Pyrrhos could not keep on claiming the Makedonian throne as long as the Antigonids – the royal family Pyrrhos pushed from the Makedonian throne – continued to control the important coastal town of Thessaloniki, the main harbor of Makedonia and the way to the flourishing Aegean trade.

Pyrrhos left Pella in the summer of 272 with a strong army to confirm his position on the Makedonian throne. After multiple skirmishing battles during the early harvest season, the Makedonian garrison of Thessaloniki decided to give battle to the Epirote army on the plains Northwest of the city. P___ tells us it was thanks to the 12 war elephants and the Celtic mercenaries (which he had recruited from among the future Galatians, passing through – and plundering – Makedonia and Trace at that time) that Pyrrhos won easily.

Sources for the subsequent battle of Thessaloniki are vague. Some say the city was stormed by force, others that it was betrayed in the aftermath of the Macedonian defeat. What is certain is that the Celtic mercenaries plundered the city and the region around it. We can only imagine what would have happened if Pyrrhos had left those Celts to garrison the old Makedonian capital of Aigai, as was his first intention.

The text:

[…]

After the taking of the whole of Makedonia, Pyrrhos of Epeiros let slip his attention on the state of affairs in Thessaly, of which he controlled the Northern part since his victory over Antigonos [II Gonatas].

[…]

He [Pyrrhos] sent emissaries to the Greek poleis around the Aegean to negotiate trade agreements. Since many of these were also at war with Antigonos at that time, they readily accepted the proposals the emissaries put forth, though he himself refused to be drawn into the politics of the Peloponnesos.

[…]

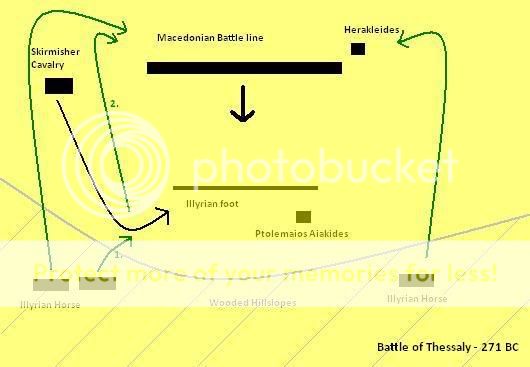

It was during summer months of the same year [presumably 271] that Ptolemaios, son of Pyrrhos, encountered an Antigonid army in Northern Thessaly, invading to retake Makedonia. Ptolemaios, there to forage for food and booty in the valleys, was accompanied by 5000 Illyrians, most of them slaves to do the foraging, but also 1200 horsemen to raid the region for booty and protect the baggage train.

Ptolemaios found himself greatly outnumbered by 15000 professional soldiers, including the dreaded Agrianians [1].

[1]

The Dreaded Argianians

The Agrianians are an Illyrian tribe that has many Thracian influences. Most now live in northern Makedonia, where they are actively recruited. The Agrianians are famed for their acrobatics and climbing ability, and are well known as an exceedingly fierce tribe. They've been recruited by the Makedones in large numbers for many years, and are now indebted to the Makedonian king for protecting them against the huge invasion of the Galatians. They wear little in the way of armor, wearing only a small round bronze breastplate that doubles as a bowl and leather greaves that protect their legs from the jagged rocks. They carry daggers and axes, both modified to use as climbing tools. Their daggers are particularly long and specially shaped to make them both climbing spikes and excellent melee weapons. They actually have a fairly advanced martial art based around these weapons. They carry thureoi and wear attic helmets, and round out their equipment with javelins. Agrianians are famous javelineers, able to throw their javelins farther and with more force than many others. They are best used as assault infantry, their javelins, speed, and axes can work wonders on heavier troops. They are fanatic soldiers who often lose themselves into a battle frenzy, able to tackle enemies with far more armor. They are among the best and fastest infantry available to the Makedonian Kingdom.

Historically, the Agrianians were used by Alexander in almost every major battle of his conquest, often to a great effect. They were fanatically loyal and were called upon as his best assault troops, able to throw their ropes and grappling hooks and use their spiked boots and specialized equipment to scale even sheer surfaces. They fought fanatically and continued this tradition under Makedonian leadership.

[…]

Herakleides [which seems to have been the name of the Antigonid general] charged his full army up the hill to attack the thin line of spear armed Illyrian infantry, only sending some light skirmisher cavalry around Ptolemaios’ left flank.

The Illyrians did not break under the charge, thanks to the encouragements Ptolemaios shouted, galloping up and down the line.

The concealed Illyrian cavalry then emerged from the trees behind both side of the battle line and charged the Antigonid skirmishers nearing the back of the Epirote left flank.

[…]

The Antigonid right flank broke under the Illyrian cavalry charges. Soon after, on their left flank, Ptolemaios and the small contingent of Illyrian cavalry on that side attacked and killed the bodyguard of Herakleides. These combined actions caused the Antigonid flanks to panic and run. Refreshing his strained left flank near the center with his own cavalry and the less tired man from the right flank and ordering the Illyrians to charge the enemy in the back, Ptolemaios broke the demoralized Antigonid center.

Ptolemaios decided not to chase to the routing army. His army had suffered and was tired. 6000 Antigonid warriors lay dead and the rest of the defeated, demoralized and now leaderless army no longer formed a threat.

[…]

Possible placement of the battlefield and deployment of the troops:

Promises

Book II, 4-11.

Background:

Soon after Pyrrhos had returned to Epeiros from his Italian campaign to march on Makedonia, during the autumn of 272, the Romans started to besiege Taras – the same city that had called Pyrrhus to Italy in 280. Although the city’s Epirote garrison, left there by Pyrrhos on his departure back home, was smaller than the besieging force, the Romans decided not to attack.

The Romans did not succeed in trying to starve the city out. They lacked the naval power to completely seal of the Tarantine harbour, through which the city continued to receive the necessary food and supplies.

This error of the Roman command and the bravery and endurance of the Tarantine garrison and population, gave Pyrrhos the time to react.

The Text:

[…]

It is said that Pyrrhos didn’t smile in the year [271], not even when he heard about his own son’s important victory in Thessaly. This [was] because during the winter [of 272] he had heard that the Romans had besieged Taras, the city he had sworn to defend.

[…]

Ptolemaios was given the command over the whole of Makedonia and received new recruits from Illyria. Pyrrhos marched back to Ambrakia [The Epirote capital] during the autumn and spent the winter preparing his return to Italy.

It is said that it was during this time he started smiling again, each time he spoke to his training soldiers about the impending invasion.

[…]

Notes:

Though the not smiling for a year part may be an exaggeration on H____’s behalve, it is clear that Pyrrhos was determined to repel the Romans once again from the territory of Taras.

This is illustrated by the fact that he left the newly conquered Makedonia in the hands of his son’s Illyrian levies, while the Antigonids did still pose a realistic threat. The Antigonids were consolidating their power in Thessaly and in the Peloponnesos. It was only a matter of time before they regained enough strength to attempt to retake their former heartlands.

It is a shame no written account of Pyrrhos’ speeches during this period has survived. We can imagine his determination must have impressed his soldiers. They needed the encouragements, since, although they were all veteran soldiers, they would be facing a numerically superior army that was confident it would repeat its success of the Battle of Beneventum.

Book II, 18, lines 3-8.

Background:

Pyrrhos had returned to Italy. He landed near Taras in spring of 270. The combined might of the Tarantine garrison and Pyrrhos’ phalanxes and elephants, and perhaps the idea of getting penned in between the sallying city garrison and the attacking relief force, caused the Romans to break of the siege and head back up North into friendly territory.

After strengthening his army with both light and heavy Tarantine cavalry and some infantry from Taras and the surrounding towns, Pyrrhos seems to have headed North, where he encountered and defeated several small Roman armies or expeditionary forces.

It appears that those small victories earned the general the support of the local Italian people, especially that of the Samnite people.

The text:

[…]

And the Bruttians said they would help, and the Lucanians said they would help, and the Samnites from the South of Samnium sent a great number of men to defeat the Romans. Pyrrhos then marched this army, 14500 men strong, half of which were Italians, to the gates of Arpi.

[…]

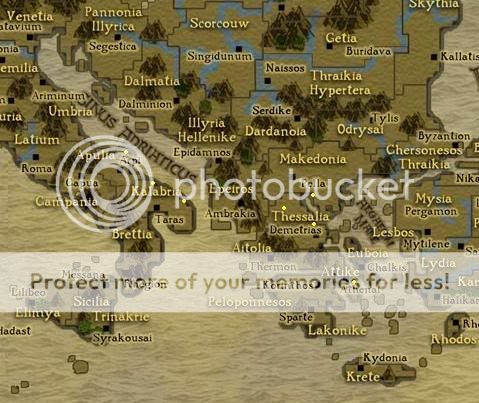

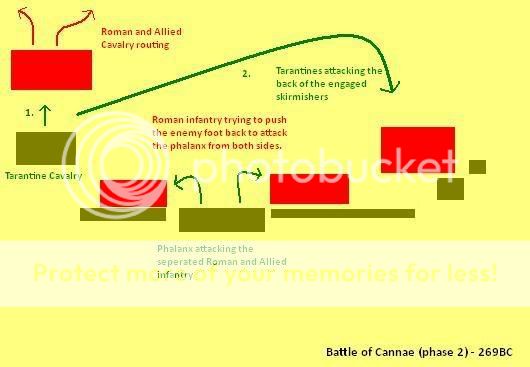

Battle of Cannae

Book II, 26-29.

Background:

Pyrrhos did not besiege Arpi, although he did fight some minor skirmishes with the garrison there and pillaged the perimeter of the city. The nearing winter and reports of a large Roman army closing in with the purpose to defeat him once and for all, forced the Epirote to return to Tarantine territory.

The Romans were confident they would beat Pyrrhos again, they had learned how to counter the elephants and phalanxes and they had numeral superiority.

The text:

[…]

In the early campaigning season of [269] two Roman legions under the command of propraetor Sextus Cornelius Rufus marched through Northern Apulia. It was a little to the South of the coastal hill town of Cannae, on the right bank of the river Ophidous [also known as the Aufidus], that Pyrrhos deployed his troops in battle formation.

The phalanx formed the centre of the Epirote battle line. On the right side stood the Samnites, the elephants and Pyrrhos own personal guard. On the left stood the Tartantines and the other Italians, along with a small number of Celts [most likely the Galatians recruited in Makedonia three years earlier].

The Romans had formed their normal fashion [the triplex acies], though with all their javelin throwers amassed on the flank to counter the mighty elephants. The cavalry covered the other Roman flank.

[…]

The aforementioned tactic [the description of which has been lost, but the surviving text make the Roman tactic quite clear – see illustration below] was to prove a mistake from the Roman commander. Pushing back the Italians on both side of the phalanx did not work because of the unexpected bravery of these men. While the Romans thus could not attack the phalanx from the flanks, this did allow the phalanx to attack the flanks of the split Roman forces.

On top of that, the Roman and allied cavalry proved no match for the Tarantines, who soon started to harass the skirmishers to support Pyrrhos, the Samnites and the elephants.

[…]

The placement of the Battle of/near Cannae, the initial deployment of the troops and the failure of the Roman tactics:

After Victory Loss

Book III, 1-3.

Background:

Pyrrhos’ losses in the Battle of Cannae were limited. He had lost three of his prized elephants and though his Italian allies had suffered some more casualties, the core of his army remained in top strength. The victory over the Romans was clear, unlike the his last victory over this opponent.

It is my opinion that Pyrrhos now made a critical error. He had just beaten the main Roman force. The other legions were busy fighting over Rhegion and defending Ariminum from Celtic raids. The Roman tactic to counter his phalanxes had miserably failed and thanks to his Italian allies he had a well balanced and motivated army. The way to Arpi lay open, but Pyrrhos did not move.

The text:

[…]

The leader of the Samnites, a man called Paius, urged the Epirote king to move North and take Safinim [this is Samnium in the Oscan dialect]. Paius told the general he could invade Apulia, take Arpi and then push [west] towards Campania.

[…]

On hearing that the army was not going to do more than patrolling the border of the Tarantine territory, Paius stepped into the general’s tent, holding high a dagger on the palm of his hands.

The guards worriedly pulled their swords, but the king stopped them and invited the Samnite to come closer. The man stopped, kneeled, put the dagger on the ground in front of Pyrrhos and left the tent without saying a word.

[…]

Pyrrhos’ forces thus lost between one forth and one third of their strength.

[…]

Notes:

Staying on the defensive had cost Pyrrhos his Samnites, who had fought so bravely in the Battle of Cannae. They did not want to fight for the cause of a Greek city, they wanted to be freed from Roman oppression. In Pyrrhos they saw a potential victor over the Romans, someone who could give them their homelands back.

In my view he should have marched upon Arpi right after the battle, taking the city undefended and demoralized after the news of the Roman loss. Pyrrhos failed to do so, perhaps because he preferred field battles over sieges, or perhaps because he was afraid the army in Rhegion would hit him in the back. We all know that this army could not have given up the siege of Rhegion. And the casualties it suffered during the actual taking of Rhegion were so high it made the army incapable to fight Pyrrhos anytime soon.

My view is that the decision not to attack Arpi, making him lose up to one third of his army through desertion and giving the Romans time to heal their wounds, was his greatest mistake as a general. And though my readers are of course free to think otherwise, I have yet to meet someone who does not agree with my view on this.

The Ambush

Book III, 9-11.

Background:

Book IV and the writings of P____ tell us that either late 269 or early 268 the veterans of Pyrrhos army were shipped back over the Adriatic Sea (see Book IV, 2). Pyrrhos now only had the Tarantine forces, backed up with some Lucanians and Bruttians, to defend Taras from the Romans.

We know through Roman annals Taras was besieged by a legion led by Marcus Curius Denatus, but the attack was soon repulsed by a sally led by Pyrrhos.

It seems that Pyrrhos spent the rest of 268 to patrol the border and defend the Tarantine territory from raiding parties sent out by the Romans themselves or their allies. It is an exemplifying for the state of ancient military reconnaissance that during such a border patrol the following could happen:

The text:

[…]

Achmetos the Tarantine had discovered the Roman camp only 4 miles away from theirs. Pyrrhos decided to attack during the night, since the Romans were low in number and apparently oblivious about the nearby Tarantine camp.

[…]

The twenty picked Bruttians climbed over the walls at the back of the encampment and started killing the sleeping men. The Romans woke up and soon killed the brave volunteers. Once they realized that these men were possibly only a small party of a larger force, they deployed in battle formation and marched out.

The moment the Romans marched out of the gate they were ambushed by the Lucanians[1] who charged them while the Tarantines showered them with missiles.

[…]

When every Roman lay dead, the bodies and the camp were plundered. Then latter was burned to the ground.

[…]

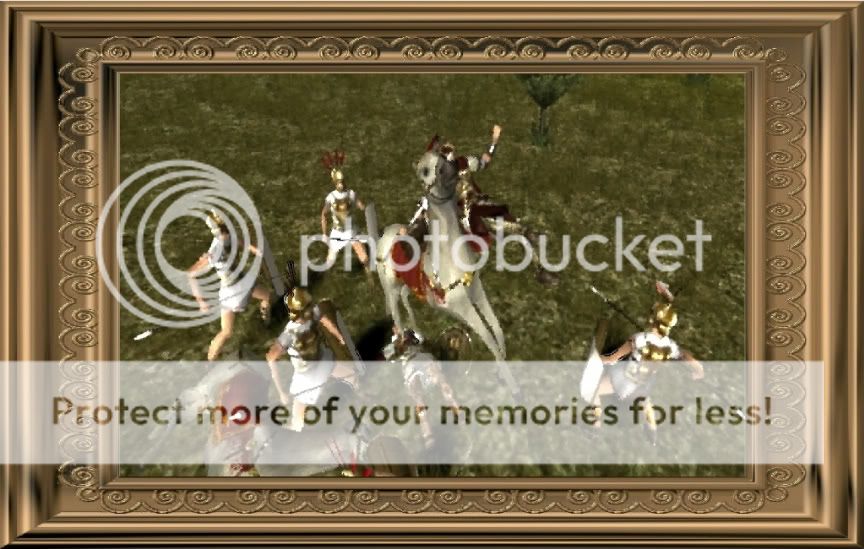

[1]

Artist's impression of the Lucanians charging the Romans:

Aichmetai Leukanoi are deployed and used as most javelin-equipped skirmishers. They run forward to pepper an enemy with javelins, and then withdraw before a counter-attack can be organised. Their job is to screen the main force of the army, and harass the enemy with a shower of javelins to disrupt their formation, so the more heavier infantry can engage with better odds. The Aichmetai Leukanoi are equipped with javelins, a knife and nothing more. Their speed is their best and only armour. Any wise general should thus try to keep them unexposed to enemy cavalry, as in melee the light infantry will quickly rout.

Historically, the Leukanoi occupied the province of Calabria in the 4th century B.C, except for the Greek coastal colonies. They were either at war or allied with their neighbours throughout their history. They allied themselves with Pyrrhos of Epeiros when he invaded.

The Battle of Demetrias

Book IV, 2.

The text:

[…]

And the veteran phalanx and the elephants there joined up with the new recruits. Ptolemaios, son of Pyrrhos, then joined them with half of the Illyrians. The other half he left in Pella.

This new army of 13700 men – 2800 of which were horsemen – was put together because news had reached Ptolemaios that the Antigonids had managed to put a puppet tyrant in Athena.

[…]

[Some information about Athena left out here, along with a long tirade about the loss of democracy as a result of the placement of the Antigonid tyrant.]

[…]

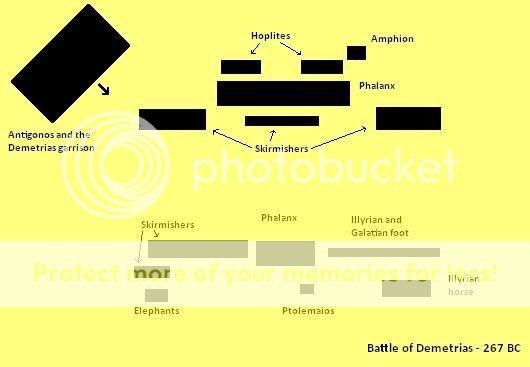

Book IV, 4-6.

Background:

Ptolemaios must have known that, thanks to the taking of Athens in 268, the Antigonids could now focus all their resources at the retaking of Makedonia. It seems he wanted to launch a counter attack before the Antigonids had time to execute their plans.

However, the Antigonids moved faster than Ptolemaios and invaded Makedonia in the spring of 267, laying waste to much of the countryside and besieging the garrison left in Pella.

Ptolemaios, in the meantime, had marched through Thessalia, encountering little resistance, to Magnesia. There he set up camp some distance North from the Antigonid stronghold of Demetrias.

D___ M____, Geographica Hellenica, VI Thessalia, 8, 35-38.

As soon as Demetrios Poliorketes became king of Makedonia in [294] he unified the small villages in the region of Pagasae. The new strategically well positioned town, called Demetrias, formed the base for most of the political interference and military attacks against Thessalia and Southern Hellas by Demetrios and his successors.

The text:

[…]

After the messengers from Pella had reached Ptolemaios, he became eager to fight the battle and to return to relief Pella. Each day he deployed his troops for battle, but the old and cunning Antigonos Gonatas stayed behind his walls.

This he did not do because of cowardice, but because his garrison was slightly outnumbered and lacked heavy foot. Furthermore, he knew that the veterans from the battle of Athens were marching back to Demetrias.

[…]

Ptolemaios’ agents inside the town had been unable to open the gates. He did receive message that one brave man, whose name was Rhouphos Bouthrotios, had broken into the house of Hieronymos of Kardia[1], who was known to have close ties with Antigonos and had written propaganda against Pyrrhos, and taken the old man with him as a hostage to his hiding place.

[…]

Great clouds of dust showed up in the distance to the South. It were the veterans, 10000 seasoned fighters, marching under the command of one Amphion.

[…]

After the front screen of skirmishers had retreated to the back of the Antigonid army, the two battle lines slowly closed the gap between them. The two phalanx bodies pushed against each other while the hoplite infantry attacked the Illyrians and Celts. Meanwhile, on the other flank the skirmishing continued.

[…]

After that bold move, much of the army of Amphion was routing. This however caused great disorder in the part of the Epirote line that had been fighting in the woods, which was soon ambushed by the skirmishers who had retreated at the beginning of the battle. The Celts and the Illyrian horsemen were all slaughtered.

[…]

On the other flank Antigonos and his skirmishers had also reached the Epirotes. This was where the light horse and elephants had joined the battle against Amphion’s troops.

Antigonos led the charge in the proper Makedonian fashion; spear in hand, at the head of his Hetairoi. It is said that when Ptolemaios saw the old king pass a few passes away, he threw his Xyston at the king. It hit him in the eye and he was thrown from his horse, where he was trampled by his own men.

Oh the horror, oh the tragedy, the great man was no more. Antigonos II Gonatas was on his way to Hades.

Oh the horror, oh the tragedy, woe all those who indulge in the sin of Hubris, for they shall fall. Ptolemaios, who had always been rather full of himself, was ecstatic after his kill and plunged into the melee, now armed with only his sword.

It was only a short time later that also this great man was no more. Ptolemaios Aiakides, son of Pyrrhos king of Epeiros, was on his way to Hades.

[…]

The losses of human live were appalling. Of the 13700 Epirotes only 2800 were able to return to Epeiros through the mountains of Thessalia. Among the fallen were all of Pyrrhos’ precious elephants.

The Antigonids had suffered too. They had lost their king, seven thousand of the veterans under Amphion’s command were slaughtered and of the garrison of Demetrias 4000 men lay dead.

[…]

[1]

Some information about Hieronymos. I'm sorry for the bad quality of the photo-copy.

Source: Sir T____ H_____, History's Histories, London, 1823, p.65.

Possible deployment of the troops at the start of the Battle of Demetrias:

Artist's impression of the after-battle massacre:

Hieronymos’ Fate

Book IV, 20-23.

Background:

It seems that the siege of Pella was called off when the army there heard about the death of Antigonos, since we now read that this Rhouphos Bouthrotios – the one we read about in Book IV, 4 – had escaped Demetrias with his prisoner and arrived in Pella during the autumn of 267.

Although we lack the sources about the why and when exactly, we can be certain that it was also in this autumn that Krateros the historian, older brother of Antigonos, succeeded him as King of Hellas, Thessalia and Makedonia and Strategos of Lesbos.

In fact only Southern Thessalia was really directly governed by Krateros. Lakonia was still completely independent and although the poleis in the rest of the Poleponessos and Attica did have Antigonid puppets as tyrants or high officials, they still retained a certain level of independence.

Makedonia of course was in Epirote hands and the plan to reconquer it had been dropped when the news of Antigonos’ death had reached the besieging force.

The text:

[…]

After being smuggled out of Demetrias by Rhouphos Bouthrotios, Hieronymos was transferred from Pella to Ambrakia, where Alexandros, son of Pyrrhos, was residing for the winter.

[…]

In spite of the nearing winter, Alexandros crossed the Adriatic Sea to see his father. He took with him the news of the death of his older brother and the captive old historian, Hieronymos.

[…]

Pyrrhos did not react well to news of the death of his oldest son and heir. He praised him for his bravery, but did not accepted his arrogant overconfidence after killing Antigonos Gonatas.

He is said to have warned everyone there about the dangers of hubris and then retreated to his private quarters. For the next 20 days there he remained, only to exit to offer to the gods. During those days, a period of mourning was declared in Taras.

[…]

Pyrrhos, still full of vengeance, declared that Hieronymos, who was by then in his eighty seventh year, should be locked up and be tortured every day. Throughout his torture he was to be told over and over again about all the lies he had written about Pyrrhos and the Aiakid family.

[…]

The Letter

Books V and VI.

Here we encounter a slight problem. Unfortunately, we do not have any surviving paragraphs of these two parts of H____’s work. Luckily, we do have some other sources. Those do require some more interpretation and speculation than H____’s work, which I consider to be a correct description of historical events.

Now let us take a closer look at some of these.

Source 1:

This is a letter 265 from a Latin soldier in the Roman auxiliary corps to family in Latium. The letter can be found in the conlectio epistoliorum Latini, which can be found in the library of Roma.

AVE . IVLIE .

INSIDIAS . MAXIMITAS . DEPVGNAVIMVS . PLERVSQVE . MANIPULI . CAESI . SVNT . BONVS . SVM . DEFECTORES . SAMNITOS . IN . FORESTA . VMBRA . ERANT . CENTIES . MILLE . BELLATORES . ESSET . OFFVNDERUNT . ALIQVI . BOVES . PYRRHI . AVDIVERVNT . DICVNT . ACCVREBAM . CELERE . MVLTI . ACCVREBANT . ATROX . ERAT .

VALE . MARCVS .

Greetings Julius,

We have fought hard in a great ambush. A great many of our men were killed. With me, all is well. It were Samnite rebels in the Ghostly Forest. It must have been a hundred thousand warriors who overwhelmed us. Some say they have heard the Pyrrhic oxen. I ran, quickly. Many ran away. It was terrible.

Stay in good health, Marcus.

Notes:

We know that the Romans lost control over Arpi to Italian rebels in 265. T____ A_____ tells us that around 5000 Samnites and Apulians took up arms against the Romans in 266. They were led by a man called Cnaeus, possible a Roman traitor. His camp supposedly was on Mount Garganus, on the small peninsular East of Arpi – the spur of the booth of Italy. This mountain was covered by the so-called Ghostly forest mentioned in the letter.

The greatest mystery the letter offers us, is of course the allusion on the presence of Pyrrhos during the battle. The Senate sent more than 15000 men the quell the revolt. Only 3000 came back. The chances are slim that this defeat was inflicted solely by the Cnaeus’ rabble.

It is possible that Pyrrhos saw an opportunity to take Arpi by supporting the rebel army. However, it is impossible that any elephants were present during the battle, since these beast were all killed the previous year during the battle of Demetrias.

The question why Pyrrhos wanted to attack Arpi now, in 265, and not four years earlier after the Battle of Cannae, probably will remain unanswered.

The location of the Ghostly Forest

Rapidly Changing Situation

Source 2:

Our second source about the taking of Arpi is an official letter from 263 from Taras to Sparta, the mother city of Taras, in which they asked Sparta to send drillmasters to train the garrison of a city called Argurippoi.

Notes:

Argurippoi is the old Greek name of Arpi, as we can clearly see through the Italotai name of the town: Argyrippa. It is therefore certain that Arpi was in Greek hands, and not in the hands of the rebels. Any mention of Arpi in Greek documents during the Roman occupation of the town simply referred to the town as “Arpoi”.

Source 3:

We learn from a pamphlet, issued in Ambrakia in 264, that Pyrrhos possessed the title “Protector of All Samnite People”. If fact, this was the only title the pamphlet granted Pyrrhos.

Notes:

Yes, Ambrakia is indeed the Epirote capital. Odd place for anti-Pÿrrhos propaganda, but it appears that the Epirote population grew tired of seeing their king fight other people’s war while letting his sons die in wars more important and closer to home.

It was Alexandros who became to be looked upon as the real king of Epeiros. He kept – forgive me an anachronism here – the country running, while his father was playing mercenary general over seas. It was also him who set up the campaign to avenge Ptolemaios’ death.

Source 4 – and Notes together for the sake of readability:

Yet another source for this period are the Athenian archives, which were under the supervision of Krateros the historian, king of Makedon, during the years 267-264. The archive, wherein all official documents passing through Athens were copied and registered, reached its high days during the supervision of Krateros, who was obsessed with having everything recorded for later generations.

One such a document gives us the information that in the summer of 265 Alexandros of Epeiros fought a battle almost on the same location as where his brother had fallen two years earlier. The scroll gives amazingly accurate troop numbers for both sides, but almost no other information about the battle. Alexandros of Epeiros, with 23530 men under his command, seems to have defeated a 30270 men strong Antigonid army, led by Antisthenes, on a plain near Demetrias.

After his victory Alexandros did not besiege Demetrias, as the Antigonids suspected. Instead they saw the Epirote army heading back North and disappearing out of sight. The Antigonids immediately sent two armies from Thessalia to intercept Alexandros.

Unfortunately for them, Alexandros had boarded an allied Illyrian pirate fleet and sailed South towards the almost unprotected Athena. The siege was short and a direct attack followed a few weeks later.

Guarding the city were around 2500 levies under command of Kalos Agreades, the youngest son of Antigonos. Although the Epirotes lost more than 4000 men in the attack, Athena was soon theirs. Kalos was captured and brought to Alexandros, who beheaded him himself. Ptolemaios was avenged.

Source 5, and Notes :

Roman official annals gives us a good idea of the events in Southern Italy during the year 263, and it seems that the Greek occupation of Arpi was a short one. The Consuls for that year, Tiberius Cornelius Blasio and Marius Aurelius Orestes, attacked both Apulia and Taras, each with two legions and their alae.

Blasio first led siege to Arpi where a left a small part of his army and then marched with the remainder of his two legions to Pyrrhos’ camp, a little to the South. Although the Roman army was defeated and the consul was killed in the battle, Pyrrhos saw no other option than to retreat back into Tarantine territory.

Orestes, meanwhile, had laid siege to Taras. We do not have account of any battle, but Orestes was granted a triumph at the end of his magistracy for a victory over Pyrrhos, although Taras had not yet fallen. So we can say with some certainty that Orestes had defeated Pyrrhos in a field battle.

With both his main stronghold under siege, one battle won with apparently enough casualties on his own side to make him retreat and one battle lost, Pyrrhos’ position looked bleak to say the least.

We have recently discovered that a famous 19th century painting, called The Death of a Roman Consul, most likely shows us the death of Tiberius Cornelius Blasio, the consul killed by Pyrrhos. The artist is unknown, but we know the painting once hung in the history gallery of Lord G___ B_____ of G_____. The Lordship's gallery was famous because it contained numerous paintings of important events during the classical era.

The Death of a Roman Consul - ca. 1834

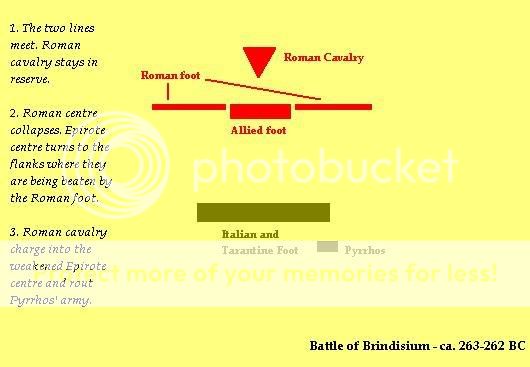

The Retreat – part 1

Book VII, 1-4.

Background:

Pyrrhos and what was left of his army set up camp near Brentesion (Brindisium) for the winter of 263. Manius Cornelius Scipio Asina, the consul who had replaced Blasio (see supra), boldly risked an attack on Pyrrhos’ fortified position. The Epirote sallied out to give battle.

Such bold and risky behaviour was often seen in Roman generals. Their offices only lasted for one year – or in the case of Scipio Asina, less – so the pressure to win an important military victory during this short time was high. Carefully orchestrating a military victory only to be replaced by the new magistrate, who then took all the honour for the victory, was the nightmare of any Roman commander.

The text:

[…]

The Roman consul had under his command the survivors of the army of the Cornelius Blasio, the consul killed by Pyrrhos. They numbered no more than what was left of Pyrrhos army.

When he saw the Epirote preparing for battle he too deployed his troops. This he did not do in the ordinary manner. In stead he put his allied infantry in the centre with his Roman infantry on the wings, not in three rows, but the hastati, principes and triarii all next to each other. His cavalry he kept all in reserve, since Pyrrhos’ cavalry was no longer numerous enough to pose any real threat.

[…]

Pyrrhos soon broke through the Roman centre, but was outflanked by the Roman foot, who turned and attacked. Scipio waited and saw that the Epirote centre was beginning to weaken, because all soldiers had turned their attention to the Romans on the flanks. Then he gave orders to his cavalry and charged personally towards this weak point.

[…]

The Epirote retreated to where Budaros, the Illyrian, lay with his fleet of Liburnes [light warship, often used by pirates]. There he was greeted by 3000 men, volunteering to go wherever he went, because they had lost all in the war against the Romans.

They boarded and set sail to Epeiros.

[…]

The Battle of Brindisium:

The Retreat : part 2

Book VII, 12-19.

Background:

The Dardanoi, an Illyro-Tracian tribe, had been a long time ally of Epeiros. They were enduring constant raiding from Getic (Dacian) invaders. Beautiful murals found in the city of Serdike tell us the story of these incursions.

Epeiros sent over its Illyrian army under the command of a Mollosian called Pialos Kassandreus, who repelled the Getic invaders. He then put Dardania under military administration and made Serdike his seat.

Meanwhile Alexandros was still out campaigning in Hellas. He had spent the autumn and winter of 263 laying waist to the countryside of Euboea, even laying siege to its most important city, Chalkis. This changed when, in early spring 262, he heard reports of two massive armies nearing Athena.

Two examples of those beautiful murals:

The text:

[…]

When Alexandros heard the Antigonid army was lead by Amphion, the general who had also lead the main army in the battle that killed his older brother Ptolemaios, he is said to have almost died of anger.

[…]

Alexandros ordered his army to move immediately and all 15000 men was transported back to the mainland in only three days.

[…]

There, with the Athena in the distance on his left, he gave battle to the Antigonids, whose men numbered more than twice his own. Althought the Epirotes fought hard and bravely, it was soon clear that they were no match for the Antigonid host. Alexandros, meanwhile, had found Amphion and challenged him to a duel.

[…]

Although their commander had been slain, their morale hardly wavered. Alexandros knew that it was time to blow the retreat. He had surely avenged his brother now.

[…]

The Antigonid army chased the retreating Epirotes and caused heavy casualties. Even more men fell when the boats were reached and it became clear that they could not carry all the survivors. Fighting broke out between the Epirotes themselves near the boats, while the Antigonids charged the Epirotes farthest from the water.

[…]

Exile

Book VII, 26-31.

Background:

Alexandros had lost his army. Athena was back in Antigonid hands. But, the Antigonids now knew the cost of killing an Aiakid. When Alexandros arrived back in Epeiros he thanked his survivors for their services, distributed the loot of the campaign and let them go home to their families.

When he himself returned to Ambrakia in the autumn of 262 he heard about his father’s retreat from Italy. Pyrrhos and his Italian army had disembarked on the island of Corcyra (Corfu). We have seen earlier that the Epirote citizens did not like their king’s engagement to the far away Taras. The general probably had expected a very different coming-home.

The text:

[…]

Pyrrhos had sent messengers to Ambrakia to announce his return. Thereupon the citizens of the city assembled and voted over this matter. Almost all agreed that Pyrrhos should no longer be considered their king and that he was not welcome with his army of foreigners.

[…]

After this they unanimously declared Alexandros as their king.

[…]

Almost all the other important cities followed the example of Ambrakia and sent messengers to Pyrrhos to tell him that he and his army were not to enter their territory.

[…]

Alexandros felt sorry for his father, but he had just excepted a ceasefire with the Antigonids. They could keep Athena, while he could keep Pella. Epeiros also had to pay a large yearly sum for the next 10 years.

The war was finally over, but he knew his father would want to renew the conflict immediately, so he accepted the offer to come to Ambrakia, where he was crowned as King of Epeiros.

[…]

Pyrrhos knew he had two options: to invade Epeiros, attack his own son and reclaim his throne or either to go into voluntary exile. He chose the latter and loaded all those who still wanted to follow him back on the ships – Budaros, the Illyrian admiral of the fleet was only loyal to Pyrrhos himself and not to the Epirote throne – and set sail to the East.

[…]

Map of Asia Minor and the Levant:

Bridge on the River Kydnos

Book VIII, 13-20.

Background:

In 260, we find Pyrrhos and his army of runaway Italians in Asia Minor. He was there either a mercenary general or simply as a friend of Ptolemaios Philadelphos, king of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Whether he was welcomed at the court as an long time ally as the legitimate king of Epeiros or just hired as a mercenary, we may never know. But it is certain that Ptolemaic Egypt needed all the help they could get at this point.

The empire of that other successor, Seleukos, was laying waste to much of the countryside of Asia Minor. All Ptolemaic strongholds there were under siege too. Pyrrhos was sent to one those important towns under siege, the city of Tarsos.

The text:

[…]

The Syrians had set up their camp between the city walls and the river Kydnos. Scouts soon found a fordable place some distance from the main road. Pyrrhos knew he had to wait though, since his army numbered only 2000 foot and 500 horse.

The horses he had been given from the stables of Ptolemaios himself, since Pyrrhos himself had not brought any on the ships.

[…]

The small army made manoeuvring easier for Pyrrhos and he sneaked closer and closer to the river without being noticed by the Syrian commander. Of the infantry he set 1500 men near the main road to cross the river at the bridge. he horse, and the rest of the infantry he took with him to the shallow spot of the river.

[…]

At this sign, Zenodotos Euergetes, governor of Tarsos sallied out. The Syrian commander Omanes Bethalagas reacted forming a battle line as close a he could towards the city. He left 5000 men to guard the bridge over the Kydnos.

[…]

The split, panicked and disorganised Syrian rearguard was soon beaten, both at the shallows and at the bridge. Pyrrhos’ soldiers then marched upon the engaged and unsuspecting Syrians.

[…]

Downfall

Book IX, 30-36.

Background:

The victory that Pyrrhos had crafted at the bridge on the river Kydnos proved to be an important one. It boosted the morale of all Ptolemaic towns of Asia Minor, which soon drove what was left of the Seleucid armies back up north, away from the Ptolemaic held coast line.

The loss of so many men proved costly for the Seleucids, since their main armies where out campaigning in Media, Parthia and even further to the East. This gave the Ptolemaios II Philadelphos the opportunity to capture the important Syrian town of Antiocheia in the spring of 259, after laying siege to it for the winter.

It is unknown whether Pyrrhos and his army helped with the taking of the city. In fact we know little at all about the actual taking of the city.

It was enormously difficult to capture a city of that size and with such fortification by direct assault, unless the garrison was ridiculously small, which is unlikely in this case.

Since the city was taken after a siege of only six months, way to short to starve such a city out, it seems plausible to me that the city was taken not by force, but by treachery from within the walls.

The fact that we know there was at least some fighting in the streets, so it seems most likely that the gates were opened by rebellious citizens who favoured the Ptolemaic Empire above the Seleucid Empire, after which the Ptolemaic troops could storm in and surprise the enemy troops at their barracks.

Pyrrhos was definitely, and perhaps tragically, there during the attack on Palmyra in the summer of 258. The independent city had happily raided the Ptolemaic territories in the Levant on request of the Seleucids.

The Ptolemaic Empire no longer recognised the independence of Palmyra and attacked. Pyrrhos and a Ptolemaic captain, seemingly under the Epirote's command, set up camp at opposite sides of the city. They soon risked a direct attack.

The text:

[…]

The Italians breached the wall first, attacking and plundering anything they saw in the streets. The Egyptians soon entered the city too and began to push their way to the citadel.

[…]

The fighting was hard and many casualties were suffered on both sides, but it was over fairly soon. The citadel surrendered and the town gave up his independence, becoming a subordinate of the throne of Ptolemaios.

[…]

Pyrrhos, who was not used to the desert sun, had watched to whole battle from his horse, in full panoply. It was during the fourth hour of fighting that he fell of his mount.

[…]

Last Words

Notes:

This was the last surviving fragment of H___’s manuscript. It was an honour to be asked to translate this extraordinary work. We can only imagine how epic this work must have been in its complete form. The amount of detail of the surviving fragments is already extraordinary.

An oral tradition, written down by P___ more than a century later, tells us that Ptolemaios II himself came from Antiocheia to visit Pyrrhos on his sickbed. The Epirote had been suffering high fever for more than a week by then and had not left his bed since.

P____, de vita Pyrrhi, XX.

[…]

The moment the Ptolemaic King entered the room, Pyrrhos stood up with great effort and bowed. Ptolemaios immediately asked him to sit down and told him the King of Epeiros was nothing less than an equal to him.

Pyrrhos answered by thanking him and saying that the King of Epeiros was Alexandros. He assured Ptolemaios that Alexandros was an able King and will continue the alliance with the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

He also asked the King to ask Alexandros to release the writer Hieronymos, if he was still alive.[1]

He then said to the king that if Tyche [Latin name: Fortuna] would have let him he would have liked to talk some more, but alas, he and her were not very good friends.

The king left the quarters and Pyrrhos fell back asleep. He never woke up again. The great general’s sixtieth summer was his last one.

It is said that Ptolemaios cried when he heard the news. He ordered the body to be picked up and brought to Alexandria to be embalmed and buried in the Egyptian fashion.

Even the Palmyrans showed respect for the general who had cost them their independence and a funeral procession by all the women of the city accompanied the body on the first few miles on its voyage to Alexandria.

The Palmyrans from then on boasted that although they had lost their independence, it had taken the best since Megas Alexandros to defeat them.

[…]

[1] For Hieronymos see Book IV, 20-23. The old writer was indeed released and lived on to see his 104th birthday.

Pyrrhos is remembered as one of the greatest generals in history. But he is also remembered as one of the most unlucky characters history has to offer. Perhaps he made a few tactical mistakes in his life (going to Italy, returning to Italy, not taking Arpi, taking Arpi), but he lacked the luck to do anything with his military victories.

On top of that there’s the whole affaire with Alexandros. He knew his son was able as King of Epeiros, so Pyrrhos went into voluntary exile, where he died, possibly of a heatstroke, although some claim he was hit by a roof tile thrown by an enemy soldier’s mother in the streets of Palmyra, which caused a wound that got infected.

--> -

--> -

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks