by Stenu Turditanikum

[Ch.11]

As the Army of Mauretania came down out of the mountains, it became clear that Bomilcar was not following us as fast as he could. Instead, reports had him in Numidia, but not defending or reorganizing the areas we'd devastated. Instead, he was recruiting a second army in the untouched regions of the country, using the sack of Kirtan to motivate a widespread Numidian mobilization.

Slowed by rivers unusually swollen and cursing the lack of bridges and reliable local guides, springtime was a rare season of slow progress by the usually tireless Army of Mauretania. Rumor trickled in from the north that Carthage had put a solid garrison behind her own walls and was raising another army which could move to defend any of the core cities around the great metropolis. Adrumento, however, was potentially vulnerable. Long a busy military recruitment area, many of its soldiers were probably marching in Bomilcar's army. While new forces had be raised for the campaign, they would not yet be a match for the full Army of Mauretania. Or so I hoped. Tarkun correctly pointed out that I might be choosing to believe the rumors simply because a march further south or back into Numidia was so unpalatable as to be unthinkable.

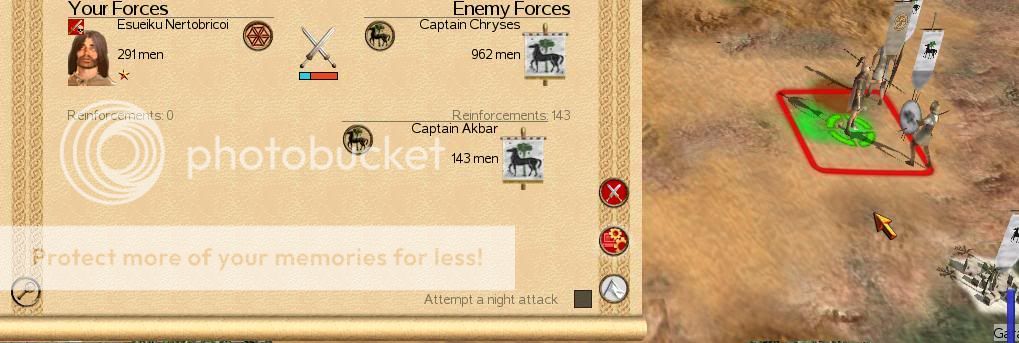

In any case, no Carthaginian army met us before we marched to the walls of Adrumento and lay siege to the town. Tarkun and I were unsure whether or not Carthage would send a relief force. Delay would allow them to continue to recruit soldiers and mercenaries by Carthage itself, but would almost certainly lead to the loss of Adrumento if we chose to storm the city. After Ippone, however, I was wary of another bloodletting against determined defenders. Bomilcar seemed out of the picture, uncertain reports placed him gathering supplies and organizing in southern Numidia. In the end, Carthage did send a strong force south to relieve Ippone. We did not yet have the option to storm Ippone before they arrived, which left us with the unpalatable option of holding the siegeworks against attacks on both sides or allowing the relief army access to the Adrumento. Tarkun pointed out that the relief army was not escorting a large train of food and supplies, which made the decision easier. We lifted the siege of Adrumento and attempted to march on the relief column before enemy could combine forces. Adrumento's garrison, however, was alert and managed to meet the other Carthaginians in the field. The supply situation was such that the enemy army did not wish to return to the walls of Adrumento, while the greater strategic concern demanded the Army of Mauretania not spend seasons marching around this army - both sides were willing to offer battle.

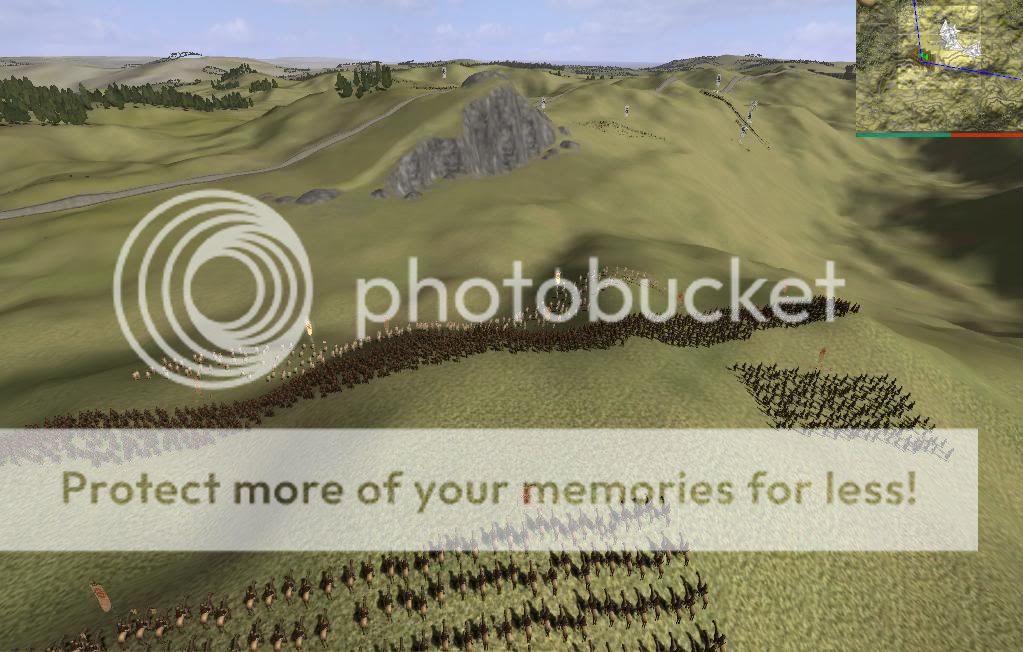

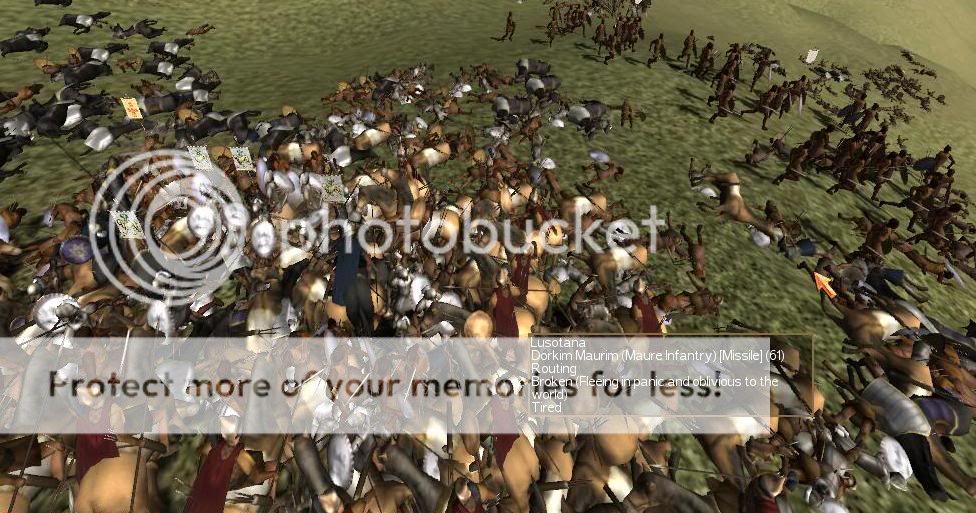

The two forces met on the road east of Adrumento, near an empty river channel, the stream having changed course at some point in history. I arranged my army on slightly advantageous ground, in a position that encouraged a split of the two enemy forces. I hoped to trap the enemy left with my right between a rock formation and the channel, while my left and cavalry overwhelmed the Carthaginian right as it came down the road. Unfortunately, the enemy commanders had their men well under control, and the Carthaginian right didn't move down the road until the enemy left had ample room to maneuver. Our right was ordered to advance slowly and begin skirmishing, commanded by my best captains. The entire left half of the army was ordered to charge hard, sticking to the plan and hoping to overwhelm the Carthaginian right before turning to deal with the enemy left in detail. I myself, accompanied by Tarkun and all of the Army of Mauretania's cavalry, would join the left, swinging all the way around to flank and hopefully crush the enemy formation. As the great mass of men surged forth, I felt my steed gather itself for a gallop, and my own bile rose in my throat. It was an ambitious plan, and I'd put myself in the thick of it. My army may have forgotten, but the one and only other time I'd found myself in combat, I had fled from the field. I feared I would show myself to be a coward again.

[An excerpt from Thucydorus of Leontini's The History of Africa, Book 11.]

The battle of Adrumento reflects most tellingly the larger struggle of Carthaginian against Mauretanian. A disciplined, compact, heavily armed force, the embodiment of the great and powerful city herself, against all the vast energy and enthusiasm of a great rural people coming into its own, represented in turn by the sea of warriors gathered by the great leaders of their people, Stenu and Tarkun. Civilization versus barbarity; armor versus mobility; discipline versus numbers; professional troops versus a nation of warriors. Both armies, like both great peoples in this moment in history, faced a fight to the death in which retreat or surrender was unthinkable on either side. A loss for the Carthaginians meant the ravaging of their very homeland, sorrow pain and death for all the peoples that had grown in this land since Dido arrived on her shores. The Maure were equally desperate. Deep in enemy territory, surrounded by potential foes, the loss of their great force meaning the end of their independence as a people. The stakes were high for all, and no soldier on the field failed to understand their very way of life was at stake.

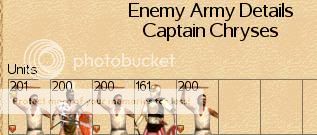

The Carthaginian army numbered 32,000 men. Certainly not the largest army assembled by that great city, but what men they were. In the midst of ongoing warfare with Syracuse and having already equipped the army of Bomilcar the previous year, in facing this threat Carthage threw open her purse and sent her best men. 12000 professional infantry formed most of the main battle line, armed and armored in the Greek fashion, drilled, professional soldiers. 9000 Sardinian mercenaries formed a solid reserve, and countered the javelins of the Maure with their own deadly bows. 6400 heavy shock cavalry, the pride of the Carthaginian nobility, also took the field, as heavy a cavalry arm as the western world has seen. But the heart and soul of the army, ready to guard the flanks or reinforce anywhere the battle would be fiercest, were 4800 men sworn to the Sacred Band. Bound to the city gods of Carthage by sacrifice and blood rites, every man of the Sacred Band had sworn never to retreat, never to flinch, to leave no Maure standing on the pain of their last breath and a curse to be laid on their children and their children's children by all the gods and Carthage itself if they should flee. Fanatics who had revived the ancient order, these men truly understood the stakes of the battle at hand.

The Army of Mauretania, thousands of stadia from any friendly city, similarly knew to a man that retreat was impossible. 48,000 barbarian warriors took the field that summer day, the fate of their people on their shoulders. The Maure could muster only 4300 light horse, and 8000 of their infantry consisted of unreliable allied tribes or nearly unarmed slingers. But 35,000 Maure infantry took the field, each one cut in the mold that had shaken Africa, a seemingly unending number of that soldier with strong sword and sturdy shield who had looked east from the Atlas mountains and decided to change the world.

Hoping to use the height of the rocky hill to their advantage, Himilco posted most of the Sardinian infantry on the Carthaginian right, supporting them with his own bodyguard and half of the sacred band. The bulk of the army advanced on the left, eager to come to grips with the barbarian invaders. But before they could do so, Stenu moved with the speed and resolve of a more experienced commander, the entire Maure left advancing well ahead of the barbarian right, moving to pin the Sardinian forces before they could unleash their arrows. This daring charge shattered the Sardinian lines, breaking the weakest section of the Carthaginian army, those with little stake in the outcome of the battle. Half of the Sacred Band, placed to stiffen the resolve of the Sardinians, held strong, but were pinned down by thrust of the Maure left, and were unable to support the overwhelmed right wing of Carthaginian cavalry, led by Himilco himself. Theages did send most of the Carthaginian left's heavy cavalry over to assist, but the fury of the Maure charge was such that by the time the reinforcements arrived, the Carthaginian right was all but destroyed.

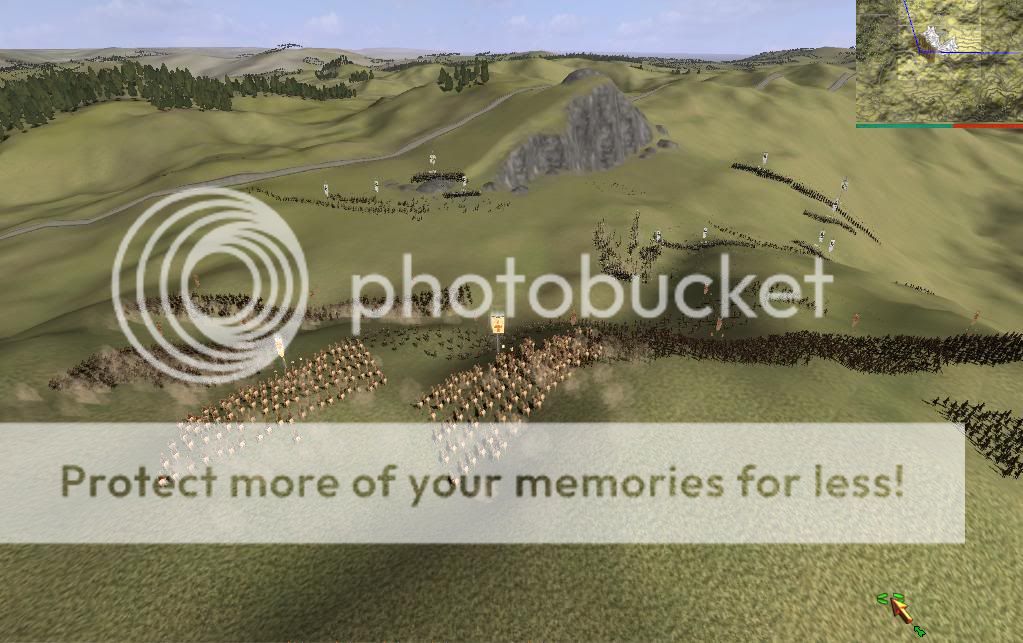

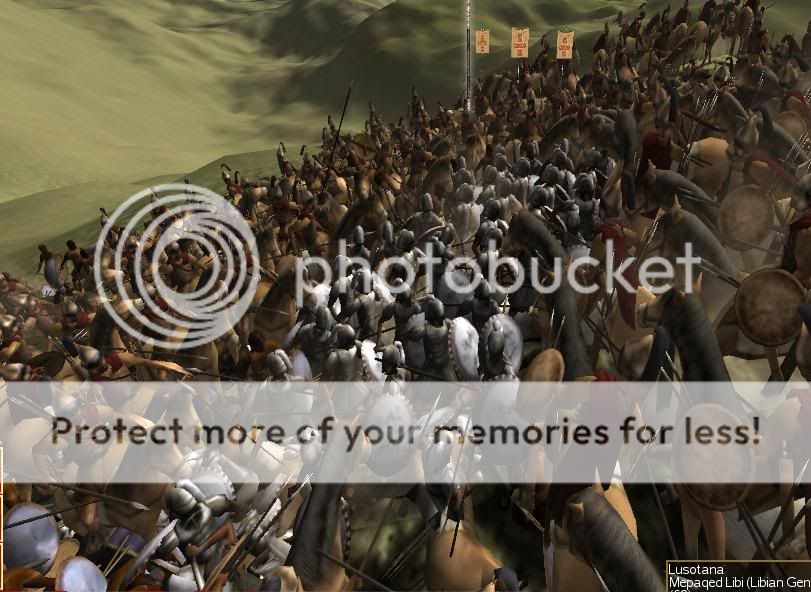

Theages, seeing the disaster developing in the other half of the Carthaginian line, sent his best men into the fray immediately, hoping to turn the Maure right, which was without cavalry. He was hampered by both the hilly terrain and the old riverbed, which itself protected the Maure extreme right flank from an encircling maneuver by the Carthaginian heavy cavalry. The Sacred Band, however, took their oaths seriously. Plunging straight into the teeming mass of Maure infantry, the pushed the Maure left back. Theages kept his heavy cavalry busy, preventing the Sacred band from being surrounded on the Carthaginian far left flank, while the professional infantry helped to stabilize the overall line and the phalanx slowly approached from the disaster on the Carthaginian right, where it had been too late to assist. Meanwhile, the remaining Sardinians on the Carthaginian left did manage to eliminate the threat posed by the lighter Maure skirmishers.

Flanked on both sides by Maure warriors, buried in javelins from infantry and cavalry alike, and finally charged by the full weight of the massed Mauretanian horse, the unit of Sacred Band on the right flank was utterly destroyed. The bravest of the Carthaginian cavalry and skirmishers escaped to harass the Maure rear, while an entire half of the Maure army swarmed to support their right, being worn down by the discipline and valor of the professional Carthaginian forces.

The combined assault of the remaining Sacred Band and the Carthaginian heavy cavalry had nearly pushed the Maure right to breaking, while the last professional reserves held off the first of the returning Maure left. The Maure cavalry, meanwhile, hunted down the Sardinian forces, knowing they could break these lesser foes, but in doing so they let the main Maure battle line remain dangerously exposed.

Finally realizing the danger posed to the greater part of their army, the Maure cavalry broke off the attack on the rest of the Sardinians and charged into the rear of the Carthaginian lines in classic fashion - until the Sacred Band placed picked men into the path of the onrushing cavalry and stopped it cold. The vigor of their assault broken, the Maure nobility still resolutely pushed forth to pressure Theages' heavy cavalry, but the unflinching efforts of the Sacred Band once again held back the defeat of the Carthaginian forces.

Theages' heavy cavalry finally pierced the center of the Maure right, but too late and with heavy casualties. The men from the Maure left were already charging back into the fray, and their bravery kept their harder pressed brethren from breaking. Himilco, however, had reorganized the remainder of the horse from the Carthaginian right and was charging in to take the Maure reinforcements from the rear, even as they threw their full weight into the line of the Sacred Band, now isolated but throwing every attacker back in to the dirt, dead and mangled by the deadly spear points of the sworn warriors. Credit must be given to both Carthaginian commanders, who made every effort to turn the tide of battle, putting themselves at personal risk time and time again. But no less credit to the heroes of the Maure effort, who had already broken half of the Carthaginian army and were now prepared to wear down the other half regardless of the cost in men.

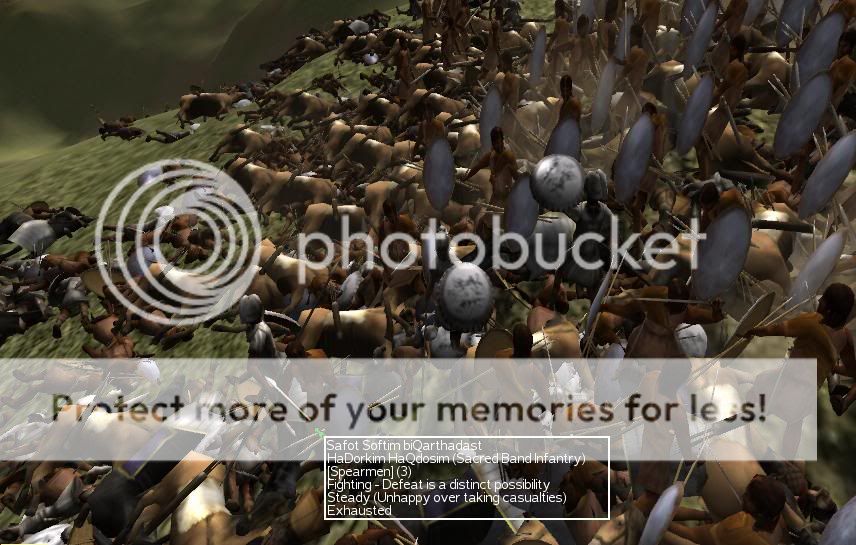

But the Carthaginian foe, despite their losses, did not waver, did not flinch from their duty. The Sacred Band held to their oaths. Having decimated the opposing infantry, the flanks and rear of the Maure surrounding the foe pulled back, as the the mass attempting to wear down the sworn warriors resisted attempts by the Carthaginian noble cavalry to break them against the spears of the Sacred Band. But the respite, if one can call a strong push into the face of the enemy a respite, did not last long. Once again the entire massed cavalry of the Army of Mauretania slammed into Sacred Band at full charge. But these warriors held. Perhaps protected by Zeus himself, perhaps having avoided the great waves of javelins denting their armor and weighting their shields, the elite of Carthage and all Africa ignored the charging spears and killed those horses foolish enough to close with them.

Throughout history there have been famed warriors who give themselves wholly to their people, accept death, and lose all fear when it comes time to march to war. The spirit of Ares moves from region to region, perhaps first settling in Egypt, where the chariots of the Pharaoh's guard once ruled the great river. Certainly the gods themselves took sides in great conflict at Troy. The Spartans, undoubtedly, showed the greatest combination of training, equipment, valor, and the support of the gods when they threw back Xerxes time and again at Thermopylae. In this battle at least, near the shores of Africa and the city of Adrumento, another group of sworn warriors fought with the will of the gods behind them.

Forced to retreat, the Maure cavalry fled the Sacred Band and circled the battle once more, as the heavy cavalry of Carthage had nearly broken the Maure line again, this time from the very direction the Maure had begun the battle.

Exhausted, the hardy steeds of the Maure struck one last time, crashing into the rear of the Carthaginian horse, more with their exhausted mass than with a true charge. But it was enough. Nearly surrounded by Maure warriors, disheartened at the spirit of men who could be twice broken and stand ready for more, Carthage's cavalry was forced to retreat. The Maure chieftains gave chase, knowing well their men could ill withstand a third great charge. Even Himilco's personal guard split into small bands, perhaps hoping to rally somewhere once more.

Abandoned by all their allies, the Sacred Band held true to their vows, choosing to die as great heroes rather than run as mortals would. Every man bleeding and covered with the gore of those who tried to break them, the Sacred Band stood. Surrounded once more by Maure infantry on every side, a natural barricade of fallen enemies began to pile up around them, and with the battle all but won, Maure units began to break and flee, fearing to face the unyielding foe, even as their cavalry returned from their long and fruitless pursuit of Himilco.

But the remaining men could not conquer an army, and as Leonidas ultimately died when surrounded, so too did the last of the Sacred Band fall, surrounded by his enemies, living and dead.

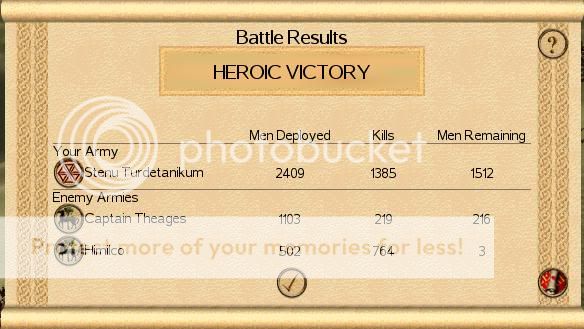

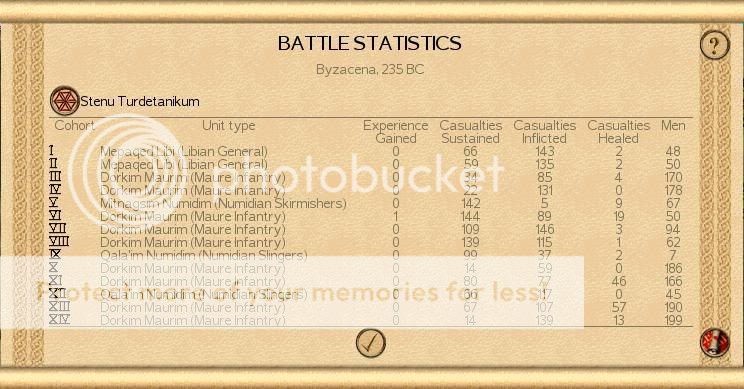

In most battles, one side or the other will quickly retreat or simply rout when it becomes clear that the other side has an advantage somewhere, or simply the gift of greater morale. In this way, armies with no choice but to fight to the bitter end and can avoid thsi fate often overcome great odds in battle. But the rare occasion will occur that neither army feels it can retreat, when both believe victory must come at all costs. So it was at Adrumento. The Carthaginian army was crushed nearly to a man, only a few thousand Sardinians and small bands of other men leaving the field alive. The Maure, for all the brilliance of Stenu's battle plan, lost upwards of 20,000 men, closer to half of their force than a third. Far from rejoicing over the battle, it is said that the Maure camp outside the walls of Adrumento that night was so silent the frightened citizens had to keep checking the walls to see if they were still there. Even loud barbarian mourning was given over to the shock of the defeat and perhaps fear that more men like those of the sworn Sacred Band would come forth to face them.

***

[Stenu]

When the battle was joined, and the first charge impacted the Sardinian lines, I lost all my fear in the battle, and felt from then on in combat only a grim determination. Even my horror was held at bay until the last of the Sacred Band had fallen. The battlefield was not cleared, nor the bodies burned. For the first time, I ordered the Army of Mauretania to simply abandon the field, and march to the outskirts of Adrumento. In a few days time, we would take the city, and I was certain the sack would be more brutal than Ippone or Kirtan. The men would fear any man from Adrumento growing up to fight them again, and I had to admit that in my heart of hearts, I was one of them. Grimly, I detailed a few officers to take their men back and loot the battlefield, but not today. No one had the strength to do it until the morrow. Ominously, Tarkun and I also avoided discussion and analysis of the new situation, wanting to leave that unpleasant task until we must take it up the next day. Both of us preferred to hear the desperately loud boasts, nervous laughter, and the men who were mourning their messmates.

[Heroic my ass. I lost a third of my men to a numerically inferior enemy.]

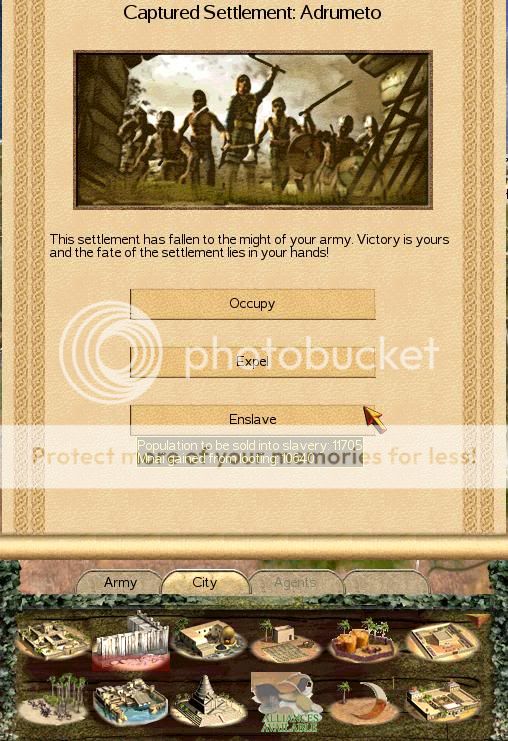

In the morning, as our army recovered our battering rams and prepared them for use, Tarkun and I agreed on the general strategic situation. Despite our losses, Carthage had suffered more. She had lost her forces in immediate vicinity of the great city, save those within the great walls themselves. We were both reasonably sure that there they would stay, to safeguard the city against unforeseen events. Only a madman would head south, so we must strike north, and return to Ippone and perhaps our base at Siga via the easy coastal roads. In the meantime, any Carthaginian subject city which they were foolish enough to leave undefended, perhaps to bolster Carthge's defense itself, would be sacked and its treasures and even the sale of its people would give us a great store of money to bring back to Maure lands. Neither of us raised the possibility that the Army of Mauretania would fail to return to Mauretania. Certainly renewed recruitment and the restoration of Maure prosperity would need considerable coin, and the Army had little and assumed the government had less.

[before the sack of Adrumento]

Bomilcar was still somewhere to the west, presumably continuing to raise Numidian forces. I was beginning to respect the man as a leader, if not a patriot. His seemingly timid actions reveal the stresses the Carthaginian government puts on their generals. Failure and defeat is punishable by shame, exile, poverty, or even death. Victory, however, was rewarded little unless it brought profit and incomes to the city. The creation of new streams of wealth brought one power and acclaim, but for some reason the character of the city assumed a defense of the new wealth rather than honoring it. If Bomilcar had found a way to force march his troops and engage the Army of Mauretania - unlikely, given the stamina of our men and their ability to march long distances - or even come to the relief of Adrumento, he would have been ridiculed at home for allowing us to get as far as we did. In contrast, by 'retaking' Ippone and Numidia, he avoids the potential stigma of defeat in the field. Organizing the Numidians gives him a military reason to delay, and if he was particularly capable he could encourage the creation of a great host by using his own considerable army to confiscate the property and punish those who didn't throw their whole resources behind a new army. I began to believe that Bomilcar's next move would not be whichever strategic stroke would be most damaging to Mauretania in the war, but whatever move Bomilcar though would bring in the most money to his family and enhance his political fortunes in Carthage.

A similar logic explained the slow war in Sicily. Carthage had a sizable army there, which a people who valued land and expansion might send to descend on Mauretania in the absence of my army. But a city who cares more about money will look at the revenues coming in from sacking Greek trading colonies on Sicily and the potential for even greater value if the entire island was subdued in the event of a total defeat of Syracuse - a motivation even more pressing with the decline in African revenues due to the war with Mauretania. Tarkun found this course of analysis intriguing, and we pondered what it would mean in future years if the war continued to drag on.

In the meantime, numerous medals were given out to the many valiant heroes in the army, those who had saved comrades or moved their fellows to halt enemy advances of their own initiative. No few were given to men who had charged everywhere on the field with Tarkun and I.

When we were finally ready to enter the city itself, the army worried itself with rumors the Carthaginians had raised yet more troops. They had tried, but the efforts consisted of little more than the conscription of Greek sailors by the port.

[aaah, Hellenic units, run!]

In the actual event of the assault, these men would refuse to fight, and many actually helped in the sale of slaves from Adrumento soon after the capture of the city.

[Adrumento before the sack]

Every important building was burned to the ground, and most of the population and all of the men were sold into slavery or killed. There was no attempt to restrain the troops and they went wild through the city, provided only they moved in units large enough to avoid being killed by citizens. I intended the men to regain their confidence and ardor after the hardships, and a good bit of whatever they wanted would hopefully be the trick. I saw Tarkun and some other officers blanch at the brutality exhibited by the men, but I said nothing and kept to the business of extracting every possible coin from the city.

We left Adrumento a burnt husk and marched north only about a week after the sack began, the men with bloodlust fully sated, and those whose conscience troubled them more than ready to leave. As we marched north, captured prisoners spread rumors I was now a Lusotann prince, odd as that sounds. Eventually we figured out that Lina Utrana Sagun had arranged with the Edetani warlord who invaded the Baleares to officially 'adopt' me, which I hope was some misguided move to legitimize the transition from client state to independent nation, but which I suspect was a way to pretend to do just that while weakening me politically back home by associating me with the Lusotann. That woman's plots are disturbingly deep and complicated.

[Can't buy a command star, but plenty of supplies and the man never tires.]

We confiscated supplies and torched buildings we passed in our march up north, but in no systematic way. The Army of Mauretania was urged to march with a new speed. As the cool season approached we were swinging wide around Carthage. I didn't want the average soldier to question why we were marching past the city with little fanfare. I myself left with a small band of scouts to see the great city from a hill away from the path of our march. The great walls were even larger than I expected, and though I could only imagine the harbor teeming with trade and warships, it seemed impossible to consider actually taking the city. No ladder would reach the tops of those walls. No scaffolding could survive the assault of the defenders above. It could not be starved out... fish and shipped grain could probably sustain it indefinitely. Doubt and thus frustration grew in me. If Mauretania must always fear invasion, but Carthage would always stand, what chance did we have in the long run? I did not stay long to look at the massive walls of Carthage or the city behind them. Security and duty demanded I return to the Army of Mauretania, so I turned my horse and the scouts followed.

The other great prize along the lengthy march back to Mauretania was Atiqa. Long denied strong walls by Carthage fearful of rebellion, it was the other major hope for plunder before the Army of Mauretania turned west once more.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

[The Ten Thousand]

[The Ten Thousand]

Bookmarks