Chapter 1: To the Furthest Altars

At the end of 266, when Satraces succeeded his grandfather, Sapalbizes, as head of their Saka tribe he was just 20 years old, having never fought in a battle nor left the region of Sai Yavuga. As mentioned in the Prologue, his courage and grit were questionable, for all that he was an acclaimed rider. Furthermore, the general Saka alliance was in tatters. There was no plunder to maintain the loyalty of the other tribes, to keep them from dispersing back to their homes. Satraces had no hold over them, although it could not be denied that trade had increased between all of the Saka and the Alans whom they made to submit. They still had control of the Silk Road depot at Sulek.

It is therefore the case that 265 was a quiet year; Satraces left Sai Yavuga and his newborn son Hippostratos, and maneuvered about the steppes trying to rally support. His cousin, Lokaksema, celebrated the birth of his firstborn daughter, Pishpasia, while Oxyboakes, the last son of Sapalbizes, was finally married at 36 to an eleven year old girl named Placidia. By the spring of 264, having failed to secure the help of any Saka tribes apart from his own, who followed him out of their customary rules of succession, Satraces entered the Kangha region, descending upon the settlement of Chach along with only the forces of his cousin, Lokaksema, and his uncle, Oxyboakes.

From left to right: Satraces, Oxyboakes, Lokaksema.

That summer, after small raids of the free-holdings in the area, Satraces took his band, for that was all they were at this juncture, and made assault upon Chach, defended by pastoral tribesmen under their chief, Homartes.

Chach was unfortified, and in typical Saka manner, the plainsmen opened the battle with a barrage of arrows from distance. The residents of the settlement returned fire, but the intimates of Satraces and his family were well armored, and found their bombardment to be much more effective. This caution has led some to suggest that Oxyboakes, the only leader who had yet seen action, took command for the attack on Chach. Our sources are silent on this matter, however, so there is no reason to doubt that Satraces exhibited such good sense.

Predictably, the sedentary tribesmen were hard put to it by the Saka arrows. When Satraces ordered the charge, there was little the defenders could do to withstand the heavy cavalry. Indeed, many of the defenders were on foot, which left them in dire straits indeed.

Homartes himself, chief of the tribes in the Kangha region, fell in the press.

The remaining defenders fled to the hills, leaving Satraces in control of the settlement and its modest population. The local warriors gave a good account of themselves though, and our sources state that Satraces was left with only 178 men to enforce his rule on the locals.

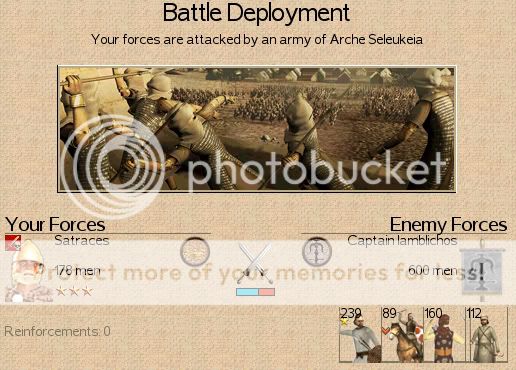

As it turns out, before Satraces had the situation well in hand, a Seleukid expeditionary column sought to impose itself on the supposedly defenseless settlement. Its captain, Iamblichos, was operating under the general mandate of the Seleukid government to maintain commercial and political ties with the west. The captain felt that any gains in the area of the Jaxartes would redound to his glory. He therefore took his forces, mostly infantry from the Iranian plateau, and moved into Kangha.

Seeing that his opponent was mostly on foot, Satraces enforced strict discipline on his men, keeping ordered ranks and peppering the approach with arrows.

The Seleukid column suffered greatly from the barrage, and when their light cavalry approached the makeshift barricade around the settlement, Satraces' well-rested force easily dispersed them with his much heavier armament.

The enemy cavalry routed, Satraces fell upon the infantry who immediately fled. The retreat was led by Iamblichos, who had realized that the situation was irretrievable. Indeed, Satraces' men caused horrific casualties on the Seleukid foot, very few managing to escape from the plain surrounding Chach.

Satraces was left, by the end of the summer, with little more than 150 men in Chach. This was not a large enough force to maintain the peace as well as hunt down the remains of the Seleukid column. In a sense, this was a blessing, as that winter an embassy from captain Iamblichos offered terms that were beneficial to both sides. For the time being, the Seleukids would remain disinterested in the Kangha region, provided that the Saka would not interfere with trade coming along the Silk Road, nor impose on Seleukid interests south of the Jaxartes. This seemed at the time to the benefit of Satraces, and an accord was therefore reached.

In the spring of 263, Moga, Satraces younger brother and second of Zeionises' three sons, came of age. Like all Saka nobility, Moga had accumulated a retinue of wealthy friends, advisors, and sycophants. These Moga readily brought to his older brother's aid, augmenting the force in Chach.

Below: Moga

Satraces, as we have commented previously, was more apt to pay attention to the world outside the immediate interests of the Saka. In this year, he heard rumors of trouble in the Seleukid kingdom. Indeed, the successor state was having difficulty maintaining its eastern provinces, and the area around Bactria, theretofore particularly hostile to the Saka, was growing in strength. Satraces could therefore see that the area of Dayuan was cut off from the west by the Bactrians.

In a shrewd diplomatic move, Satraces sought to temper relations with Bactria, while moving south of the Jaxartes to plunder Alexandria Eschate, the last Seleukid outpost in the immediate vicinity.

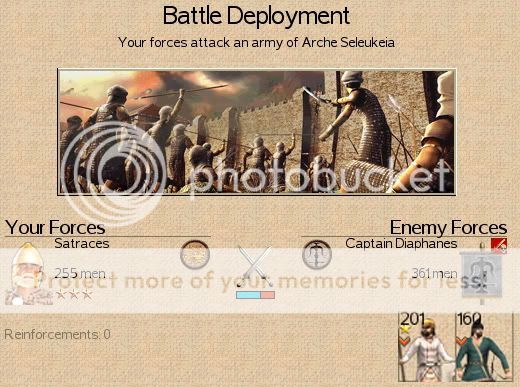

The Saka chief wasted little time taking his men across the river and moving against the garrison of Furthest Alexandria. The bulk of the province's fighting force was occupied elsewhere, and only a token force remained.

The defenders were entirely on foot, and could do little to withstand the skillful horse archers, who themselves were heavily armored.

The Seleukid spear men, conscripts from Parthia, withered under the storm of Saka arrows.

When Satraces' arrows were spent, he ordered the charge. Here the Seleukid garrison seems to have maintained some semblance of discipline, as our sources claim the melee was hard fought, with the heavy horse finally gaining the moral advantage when the commander of the garrison, Diaphanes, fell in the onslaught.

The Saka warriors raced to the center of the town, cutting down the last remaining pockets of resistance. Lokaksema, Satraces' cousin, pressed the defenders relentlessly, earning a greater reputation thereby.

In short order, the enemy was dispersed, and the Saka were allowed to loot the town. All manner of goods were taken and the military infrastructure set up by the Seleukids was completely destroyed. Satraces, however, in a move that was very much in his character, did not allow the Furthest Altars of Alexander to be disturbed.

The remainder of the year 263 was spent establishing control in the Dayuan region and accounting for the booty gained in the sack of Alexandria. Here our sources first mention Satraces' desire to follow in his grandfather's footsteps, giving most of the booty to members of other Saka tribes to secure their loyalty.

It is unclear whether at this point Satraces had any such designs, as there is no evidence of any other tribe than his own taking part in his early military operations. However, he is not supposed to have kept the booty for himself and his close associates, and it therefore may be possible that the debts incurred by his grandfather were somewhat lessened by the general surge in wealth spread about the Saka tribes over the recent years since the disaster at Gava Haomavarga.

The year 262 contained little of military or political note in the orbit of Satraces' command. In the spring a sizable column of Seleukid troops passed through Dayuan, but the area around Alexandria Eschate had become such a place of terror for the Seleukids that the column passed west and out of the region. The central government of the Seleukids had given up on regions that far east, and were now concerned with fighting against the Parthians and Bactrians for control of the Iranian Plateau.

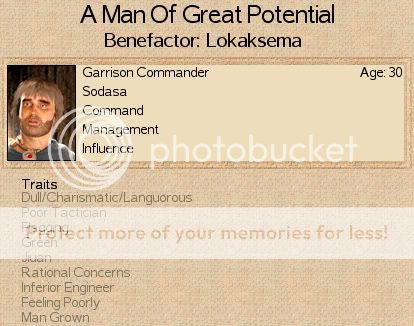

In this year Lokaksema adopted invited a small chief of another Saka tribe, by the name of Sodasa, to join his command. The young Lokaksema had been introduced to the much older Sodasa in the years leading up to the Haomavarga disaster, when the various Saka tribes were in the habit of socializing. Our sources suggest that the two were romantically involved, but there is too little evidence to explain this rather odd companionship. In any case, Sodasa joined Lokaksema with his personal retinue, further increasing the forces under Satraces.

Below: Sodasa.

In this year as well Satraces celebrated the birth of his second son, Zeionises. The celebrations were short-lived however, as Satraces made a bold decision. Our sources claim that his naming his child after his own father made him think of the heavy blow to Saka honor in 266; whether it did or not, in the winter of 262, Satraces moved his forces east across the mountains and into Dahyu Haomavarga.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks