Here begins the record of the career of Toadius Assistum Secretarii. Having begun my service to our most divine Augustus Theodosius Flavius in year 373, I do set in writing those events which have occurred during my tenure. It is my hope that this chronicle will be of use to my successors, so that they may better understand the history of the glorious empire that they serve.

When I first had the honor to be called into the presence of Augustus Theodosius Flavius, I was struck by the innate majesty that seemed to flow from him. His massive intellect was surpassed only by his total confidence in the Empire's superiority and his own divine mandate to lead it further glory. Not a single lie passed his lips, for he had no need to utter such. His word was more than just wisdom, it was law. Those who were not won over by his supreme abilities in all areas of earthy importance were converted by his regular expressions of power. Woe be to those who did not sufficiently acknowledge our most wondrous Augustus, for he had little mercy for any who doubted him. Such was the force of Theodosius' will that even his father Julius Flavius, Governor of Thessalonica and son of the late Augustus Julius Flavius, did not dare to protest being passed over in the line of succession. Even more pity was due to his foes, for Theodosius had developed a fondness for the sight of blood and he often entertained himself with enemy prisoners or the occasional misbehaving servant.

My service began as a request by Theodosius for an individual to make a complete survey of the Empire, so as to provide a reckoning of all assets, military forces, governmental positions and other such information as may be found useful to Augustus in exercising his divine will. This information was compiled in a massive tome known as the Noonday Book, for it was ordered that it be finished by noon on the following day. This deadline was as final as judgment day, so I summoned all my strength and exhausted five pairs of sandals and thirty-seven quills in collecting the information and transcribing it by the deadline. The results showed an empire in flux.

Theodosius had completed his grandfather's work to convert the entirety of the Empire to the light of Christendom. As of 373, all provinces acknowledged the irrefutable nature of Christ as our Lord Supreme. Some areas still held small Pagan minorities, but these were being converted at a steady pace and a complete union of peoples under the one true God would follow within the decade.

In the West, the provinces south of the Danube were peaceful and prosperous, but the rampaging hordes of Hunnic, Gothic and Sarmatian barbarians threatened to bring chaos and bloodshed to our realm. The Danube Border Legion, under the command of the talented general Manius the Mean, had balked before the seemingly endless flood of Huns to the north. The general had abandoned his position at the eastern crossing of the Danube and allowed the Huns to enter our territory unmolested. Now, with fully half of their peoples in our territory, a conflict was feared inevitable.

In the East, the heretical Sassanid masses had fallen back before the military might of the Empire. A large army, headed personally by Augustus Theodosius Flavius, had struck a great blow and taken Harta from the enemy. He was now poised to march on the Sassanid capital of Ctesiphon after a short campaign to clear the remnants of the defeated enemy forces from the area. A second army stood guard at the main river crossing north of Harta, to blunt any enemy counter-attack that might emerge from this region. A third Eastern force of small size, but high quality, was besieging the independent town of Dumatha and was expected to gain control of the region promptly.

Despite the successes the Empire had experienced, it was in a state of disorder and suffering from massive economic inefficiency. When Theodosius first examined the records of the Noonday Book, he ordered the immediate execution of his previous advisor and appointed me in his stead. I swore to enact his majesty's every command and to assist him in any way he saw fit. Within weeks, the reorganization of the Empire had begun. Theodosius found himself in control of an Empire that turned a mere 6,000 denarii profit per season and whose military forces were scattered throughout the provinces performing garrison duty. No small nation, let alone our glorious Empire, could grow successfully on such a meager income. Augustus, in his divine wisdom, decided to devote fully three-quarters of seasonal income to economic improvement for the foreseeable future. He was determined to transform the Empire into the single most dominant economic power in the world. Taxes in each province were raised to the maximum that the population would bear and a systematic restructuring of the garrisons began.

In addition to the masses of Limitates, garrisons were even composed of Legio Lanciarii spearmen, Comitatenses heavy infantry, Eastern Archers and the supremely expensive Hippo-toxotai horse archers. This was bleeding vast sums from the treasury each season. Augustus personally examined each and every province under the control of the Empire. All garrison forces in non-threatened areas were to be replaced immediately with peasant militias. These forces were cheap and able to quell any local discontent on their own. Over the next four years, this reorganization would continue, with the stronger garrison troops being transported to Constantinople and Antioch for refitting and organization into front-line legions. All garrison troops unable to make such a journey easily, such as on Crete and Cyprus, were simply disbanded and replaced. The only exception to this rule was Alexandria, where nearly a third of a legion of Comitatenses and Eastern Archers were held in quarantine to prevent the spread of the terrible plague that was ravaging the city.

The effects of Augustus' most inspired reforms, the Empire was showing a profit of 9,500 denarii per season before the summer of 373 had even ended. Many reinforcing units were now on their way to assist in the war with the Sassanids and the foundations of the Second Danube Border Legion had been laid. This great internal movement of forces also revealed that many disloyal Romans had taken up arms as rebels and were obstructing trade routes across the empire. All rebels would be crushed or expelled from the Empire's territory whenever the forces could be spared to do so.

As this momentous season came to a close, Augustus diverted his attention to the military situation and formulated his grand plan of conquest. If the Empire was to achieve its destiny as the dominant power in the world, its economy must flourish unmolested. With most of the eastern provinces under control, Augustus decided that this area would best serve as the financial breadbasket of the Empire. The Danube border was to be held at all cost and the Balkan provinces strengthened, but there would be no expansion west or north. The east must be pacified first, so as to supply the resources for the mighty struggles that would undoubtedly be required later. With the first blow already struck upon the Sassanids, Augustus set out on an ambitious two-pronged assault on the enemy. He would personally lead the main Harta force towards Ctesiphon while the northern river blocking force would advance north to Artaxarta. So he decreed and so it was.

Good news and bad news reached my ears as winter fell in 373. I decided to give our most divine (and harsh) Augustus the former first in an attempt to lighten his mood for the darkness that would surely follow. The Huns, it seems, had decided that the lands north of the Danube held richer pickings for their hordes and had moved all of their forces out of the Empire's territory. Manius the Mean returned to his post guarding the eastern Danube crossing and he was ordered to stand his ground, even if all seven mighty Hunnic hordes decided to assault him at once. Under no circumstances was he to abandon his post without orders. Following upon I gave Theodosius the first trinkets to arrive from the newest acquisition of the Empire, Dumatha. The small garrison had sallied in a last-ditch attempt to save themselves, but they were cut down by Eastern Archers and Comitatenses with little loss to our own forces. Pleased beyond measure, Augustus ordered this force to remain in the province while order was established and a garrison was trained.

Seeing that my most supreme Augustus was content with this information, I then told him of the tragedy that had befallen Captain Nepos and the northern force destined for Artaxarta. While encamped on the main road, they had been assaulted by a very large force under the command of the Sassanid general Narses.

Outnumbered two to one and with inferior troops, Captain Nepos fell back but to no avail. Narses followed and forced battle upon the brave captain, who formed his men into a strong defensive formation on the barren plains.

He personally positioned and encouraged every single man in his force, but his hopes were dashed instantly as the enemy began the battle with a simultaneous charge by cavalry units into the sides of his position. While the brave Limitates on the left flank were able to throw back their light cavalry attackers, the right flank suffered cruelly under the hooves and blades of fearsome heavy cavalry, whose horses themselves were clad in armor.

As the main enemy force closed, Captain Nepos threw all he could spare at the immovable foe in a desperate attempt to restore order to the front rank. As Romans fell before the cruel Sassanid blades, he led his own small force of Hippo-toxotai to assist in the desperate effort. Alas, after a brave struggle he was cut from his saddle and trampled, causing most of the men nearby to flee in despair. As half of the army broke and ran, the enemy infantry appeared before the remnants. The storm of arrows and blades that followed was too much for the men and they fled almost instantly upon contact with the enemy. A full two-thirds of the northern force had been slain or captured while a mere sixty foul Sassanids had fallen. Not only had the northern thrust on Artaxarta been stopped, Narses now had an open road to Harta.

I feared that I would not long outlive Captain Nepos, but my concerns were unnecessary. Augustus bowed his head and chastised himself for his arrogance. He stated that he had underestimated the Sassanid people. The march north had been ordered under an air of total Roman superiority over the smelly desert dwellers. Theodosius Flavius vowed never to make such a mistake again. He sent word back to hurry on the reinforcements coming from their former garrison posts and vowed to stand before Harta until a second force was ready to hold the region. He retired to the scant luxuries that the desert city of Harta could offer and continued his economic reforms, determined that his idle time would not be wasted. In this, he showed supreme again, with seasonal income now rising to the entirely satisfactory level of 14,000 denarii, a full two and a half times increase over the previous winter.

As Emperor Theodosius passed time in Harta waiting for the reinforcements to arrive, I was given the difficult task of breaking good and bad news to him. Since my previous experience had not resulted in the removal of any body parts, I decided to use it again. The plague in Alexandria had passed and the garrison there was now free to travel. Augustus was ecstatic and ordered that the Comitatenses and Eastern Archers be immediately refit and then marched north to assist in the war with the Sassanids. The prospect of more well-armed and well-trained Roman soldiers on their way to his forces pleased him greatly. It was then that I had to break the news of the folly of the diplomat Valerius Atilius. He had been dispatched with a small fleet to establish contact with the barbarian tribes north of the Western Empire and to observe any conflicts that might be on-going in Gaul. Upon landing in southern Gaul, it seems that this foolish patrician had decided to take it upon himself to raise some extra coin for the Empire. He had attempted to sell maps of our provinces to the Western Empire for the outrageous price of 5,000 denarii. Not only had the Western Empire refused, but they were so insulted by the offer that they cancelled their Alliance with us. This unprecedented division between the glorious Roman Empires put at risk the provinces south of the Danube and threatened to disrupt trade income. I was fortunate once again that Theodosius once again did not blame the messenger for the message. He ordered the immediate execution of the diplomat and decreed that every effort be made to regain the Western Empire as an ally.

As a temporary measure to secure the Danube region, an alliance was made with the Sarmatians who had occupied Aquincum. Interestingly, the diplomat in Gaul never seemed to receive word of his death sentence and Augustus continued to receive bi-annual reports on the situation in the region from him. While this information was useful, Augustus Theodosius continually mentioned how he hoped the diplomat's next message would be delivered along with his head.

As the seasons turned cold again, the expected offensive from the Sassanid General Narses finally arrived. Unfortunately, our scouts were caught and slain before they could report back on the advancing enemy. As a result, they surrounded and besieged Harta with Augustus Theodosius Flavius still inside, but with the strength of his forces still outside! Despite the panic that soon started to spread throughout the city, the supremely wise and confident Augustus barely even acknowledged the situation. Reinforcements, he assured us, were close at hand and when combined with the army camped outside the walls, they would surely break the siege when the weather warmed.

Through the use of runners slipping through the enemy camp, Augustus was remarkably able to continue managing the affairs of the Empire during this short ordeal. He had spent a great deal of time thinking over the diplomatic situation in the west and had decided that the Sarmatians were the wrong allies to have. While they had conquered and plundered with success, they were at war with the Goths and the Huns, both tribes of great strength. He ordered that the Sarmatian alliance, barely half a year old, be broken and a new one forged with the Huns and Goths. While the latter rudely refused, the massive Hunnic armies agreed to the deal. It was hoped that this agreement would secure the Danube from the worst threat in the region and distract the Western Empire, where the increasing strain on relations was showing. If conflict were to be inevitable, better to let the stinking barbarians bleed instead of good Roman soldiers. The now refitted forces that had been relieved from garrison duty in the west were assembled and dispatched to deal with an extremely strong rebel force outside Thessalonica. While this battle was successful, the inexperienced legion took many casualties and was forced to return to Constantinople for a second refitting before setting out a second time to take its place as the Second Danube Border Legion, guarding the western crossing.

As the snows melted and the year 375 began, Theodosius' decision to ally with the Huns proved to be the right one. The Hunnic horde had turned on its former allies, the Goths and besieged them inside their new homeland. While the prospect of a newly roving Gothic nation was worrisome to the Empire, it was a better alternative than a hostile Hun nation and it gave the Second Danube Border Legion more time to reach its post.

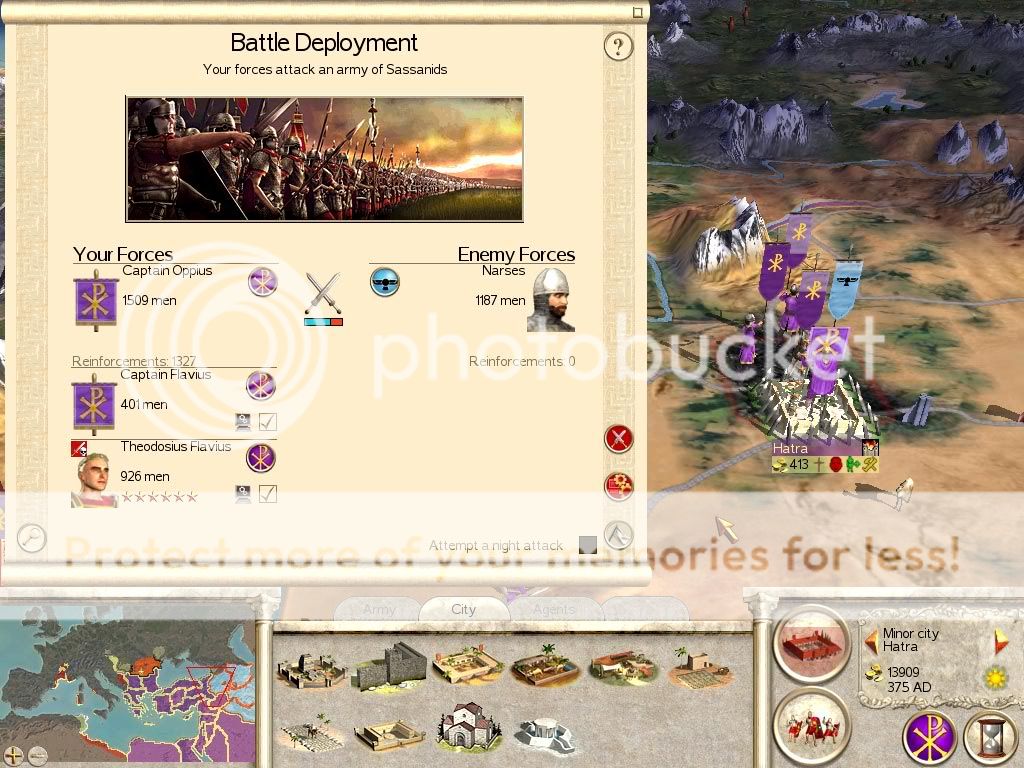

In the east, the time came to break the siege on Harta and resume the offensive against the Sassanids. Despite his expertise in warfare, Augustus Theodosius chose to allow Captain Oppius, commander of the main relief force, to determine the battle plan. This was a humble, yet wise decision since the Emperor was only able to exercise direct control over peasant militia and several Limitates units.

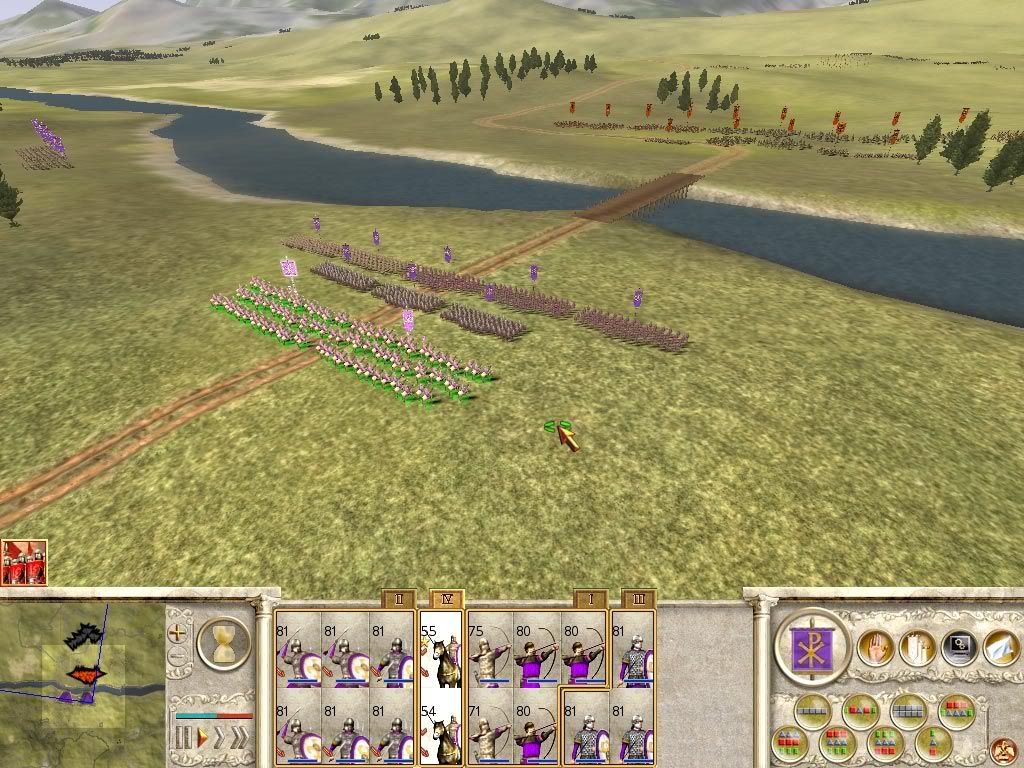

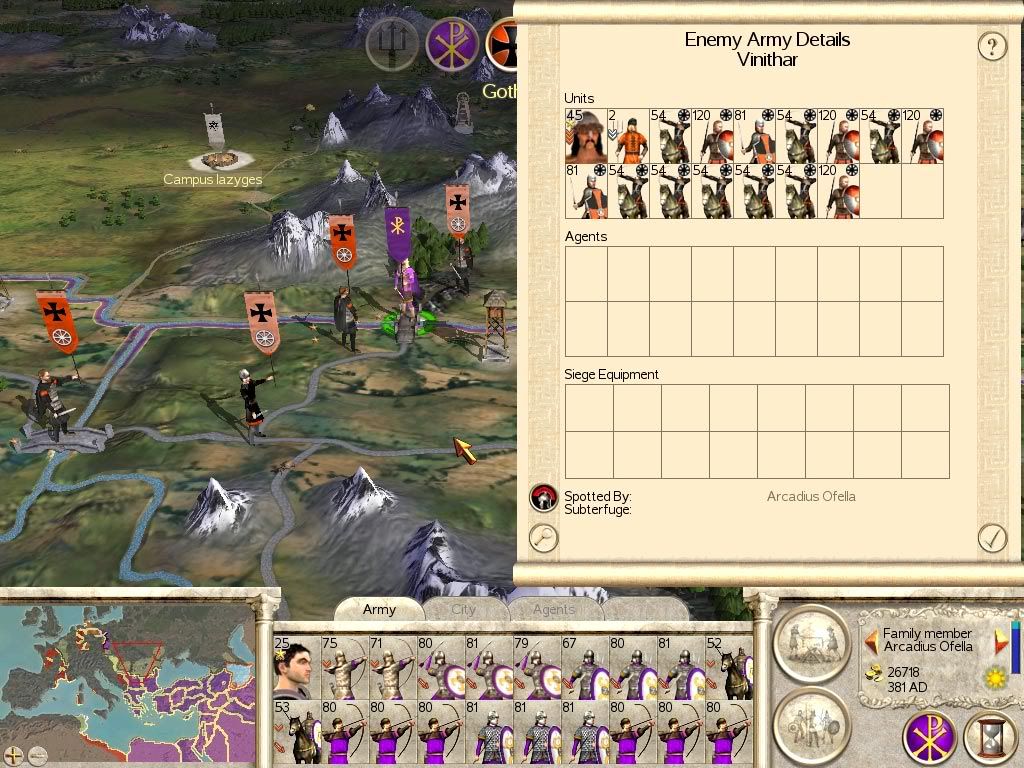

Oppius took the strength of the relief force under his personal command. This force numbered some nine units of Legio Lanciarii, five units of Comitatenses, four units of Hippo-toxotai and a few other assorted supporters. This army would attack Narses' force from the west. Simultaneously, the remained of the relief force, comprised of four Limitates, would attack from the north and Theodosius would sally forth with the Harta garrison from the south. Oppius chose only to command his own force, leaving control of the northern flankers to a Captain Flavius and letting the Augustus do what he believed best from the south.

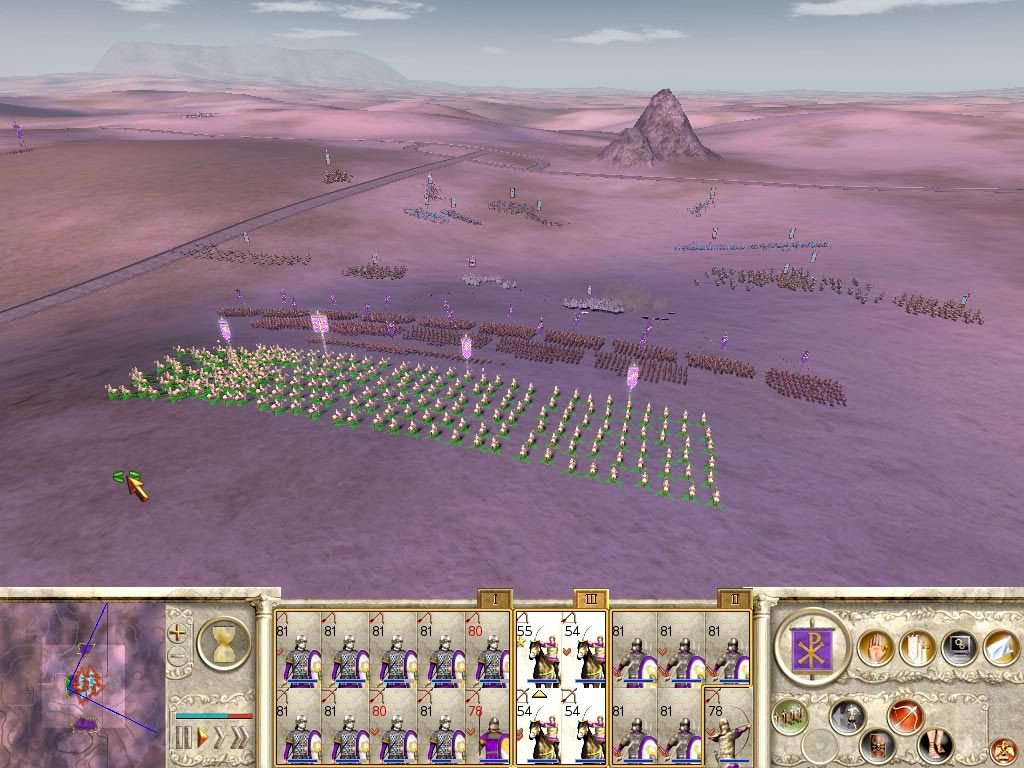

As the main force closed, Oppius saw that Narses had chosen to draw up his army at the foot of an isolated mountain, protecting his rear from attack.

This was a cunning, but fruitless effort though, since his northern and southern flanks were unprotected by natural boundaries and both reinforcing armies arrived at the battlefield exactly on time. Oppius formed up into a great double line of infantry, with spears in front backed by the swords of the Comitatenses. The Hippo-toxotai remained in the rear to fire volleys over the heads of the infantry at the enemy.

Seeing the three armies converging on his position at once, Narses made a desperate gamble to try and save the day. He diverted two small infantry forces to tie up each of the flanking armies and closed rapidly on Captain Oppius' main army with all of his cavalry and the remainder of his infantry and slingers.

As the cavalry neared the first Roman line, they saw the gleaming spearpoints and their horses balked. Unable to charge home into such a mass of metal, they halted and the horse archers began raining arrows down on the steel clad enemy. Oppius knew that the enemy had misjudged their position however, as the hill's height have the spearmen the range to hit the enemy cavalry with their javelins. Once the rain of steel began, it was clear that Narses' gamble would fail. The Sassanid cavalry crumpled with increasing rapidity under the bombardment.

Oppius unleashed the Hippo-toxotai upon the enemy as well and soon all but a single unit of slingers were running for the cover of the mountain.

With the main line broken, Captain Oppius split his force in three. The spear line advanced upon the retreating enemy while the second sword line swung north and the Hippo-toxotai moved off to the south, all as fast as they could move. Oppius hoped to catch the flanking forces from the rear and completely rout the enemy army. The Hippo-toxotai achieved with only a few volleys. Outflanked, with the majority of their forces running for safety, the southern Sassanids units broke too. The Comitatenses force sent north proved to be unnecessary as the Captain Flavius' Limitates routed their opponents unassisted. With the enemy in full flight, the Hippo-toxotai were ordered to charge home and slay the broken men, leaving a carpet of dead and dying in their wake.

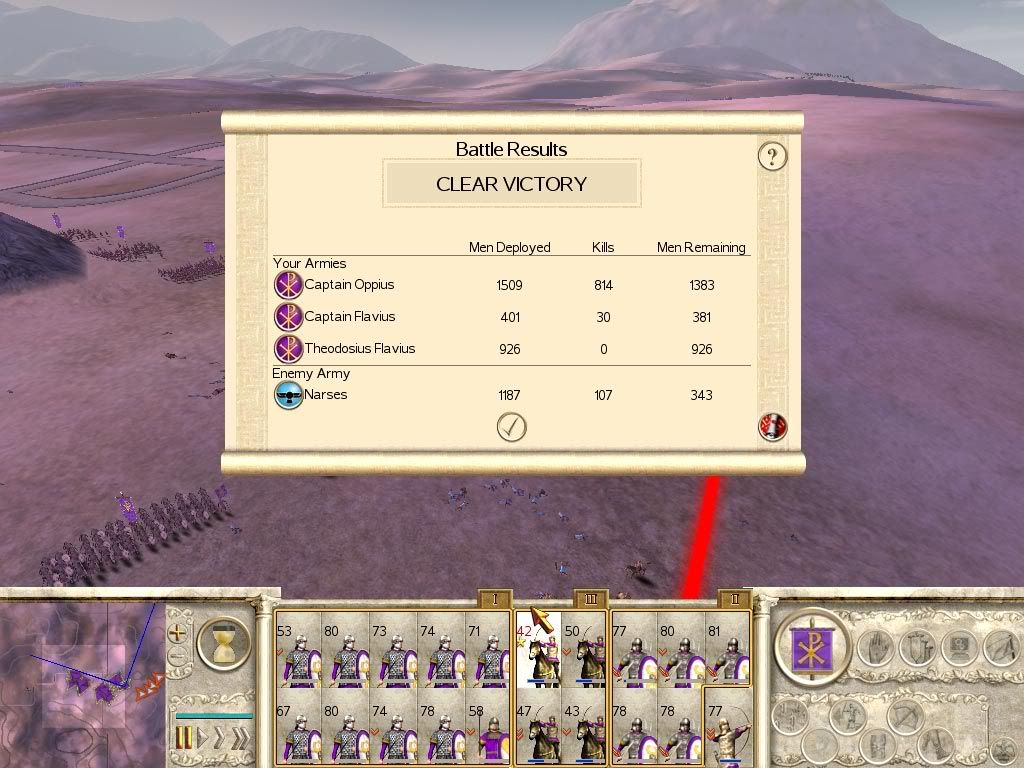

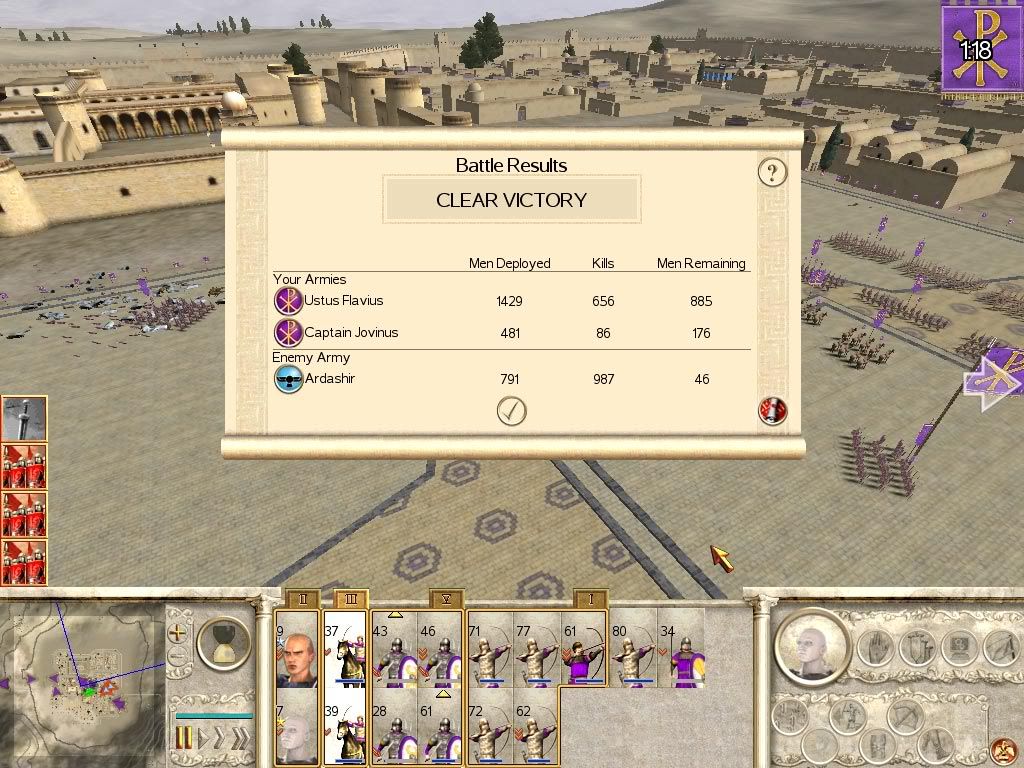

Though Narses himself managed to escape this slaughter, his army was gutted. A full three-quarters of the Sassanid force lay on the sand north of Harta for the loss of barely 150 Romans. As the peasants came out from the city to scavenge from the dead, Theodosius personally greeted Captain Oppius and gave him command of Harta's defenders. With Narses defeated and more reinforcements arriving in the area every day, the Emperor would not even wait a night to celebrate the victory; it was time to march on Ctesiphon.

As summer turned to winter, a messenger from the west arrived in the army encampment on the road to the Sassanid capital. Two significant events had occurred. First, with the Celtic conquest of Britannia complete, the Romanized natives had risen up against their new lords. The Romano-British had emerged and only the Lord knew who the victor in this struggle would be. While interesting news, Theodosius dismissed it with a wave of his hand, for he knew that the next message would change the course of history.

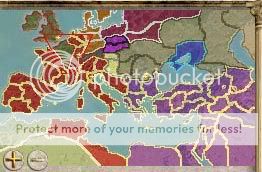

The downward spiral of diplomatic relations with the Western Empire had finally reached bottom. In a move obviously aimed to restrict the rapid growth of our economy, currently providing some 15,000 denarii per season, the Western Empire blockaded Crete. While only causing a minor decrease in income, this outright violation of free trade and infringement upon Theodosius' territory could have only one response: war. So it was that the brotherly alliance between Romans came to an end. On this day in the winter of 375, the Emperor in the East vowed that the Roman world would someday be re-united under one banner. The ignorant fools in Rome had sealed their own fate. It might take decades and Theodosius would likely not live to see it, but he declared then and there that the rightful heirs of Caesar and Octavian would someday command an empire from Iberia to Arabia.

The time for action against the West was not yet upon us however. With the Western Empire embroiled in war with the Vandals, Franks, Celts, Saxons, Alemanni and Berbers in addition to Theodosius, it would be some time before they posed a serious threat to Eastern security. For now, Theodosius ordered that the First and Second Danube Border Legions be strengthened and that a Third Legion be prepared to defend Roman soil in the west. With this done, he returned his attention to the war in the East. Once the Sassanids were conquered, there would be plenty of time to deal with the Empire's other enemies.

Camp was broken and the army was once again on the march to Ctesiphon. With the small Dumatha conquest legion on its way to assist, Theodosius expected to begin the siege of the Sassanid capital in the New Year.

Just before the Empire's finest legion finally arrived within sight of Ctesiphon, news arrived from our allies in the west, the Huns. They had taken the Goth capital and sacked it, forcing the people back into a roving horde. News from the governor of Sirmium reported that a significant number of these nomads had somehow slipped across the Danube and were in the mountains south of Sirmium. The Second Danube Border Legion, already on its way to the western crossing, was instructed to march to the area round Sirmium to deal with any potential hostilities with the unwashed mob.

Valerius Atilius, the diplomat with a death sentence, sent word that the Franks had agreed to an alliance. This pointless diplomatic gesture to a nation that had no meaningful interaction with the Empire further solidified Theodosius' desire to see a certain head on a certain stick.

As Augustus neared Ctesiphon, spies reported that while the Sassanid King was residing in the city, a sizable force of slingers and skirmishers were encamped outside, unaware of our approach. When informed of this, Theodosius immediately ordered a decisive action to eliminate this enemy force so that the slingers would not be available to harass our men as they stormed the city walls.

A night attack was ordered, with the Emperor personally commanding the army. The cover of darkness hid our approach and allowed us to take the enemy force before the remainder of the garrison could come to their aid.

As the legion neared the forest in which the enemy was camped, the Sassanid captain charged out at us with his contingent of heavily armored horse. The remainder of his men retreated in an attempt to escape while their leader bought time. While strong, the veteran Roman forces quickly cut him and his men to pieces. Once again the Hippo-toxotai were unleashed upon the unarmored enemy as they tried to retreat, cutting down all but a handful of the enemy.

As dawn broke, I looked out upon the massive stone walls of Ctesiphon. I could see commotion on the walls as the sentries saw the force surrounding them. In the distance, hammering and sawing indicated that the siege engines were already being constructed. Now it was just a matter of waiting.

As the winter of 376 set in, preparations for two major battles were underway. In the east, the Emperor's own army was completing its seven massive siege towers. When the seasons turned he would unleash the might of Rome against the enemy King, cowering inside his capital. In the west, a significant portion of the Gothic horde had arrived outside the gates of Sirmium. While hostilities had not yet been declared nor the city besieged, it was clear that they intended to sack the Empire's western-most province. The First Danube Border Legion under Manius the Mean was ordered to abandon its post at the eastern crossing and proceed west with the Second Legion. While they would not arrive in time to prevent a siege of the city, they would ensure that it did not fall to the horde. If the Goths meant to fight, the Emperor meant for them to die.

The year 377 opened badly for the Sassanids. As the weather improved, the Roman siege engineers completed their work on the great towers that would carry their men over the large walls of Ctesiphon and into the heart of the enemy capital. As was tradition with the beginning of any season, the servants and messengers had lined my Emperor's royal campaign tent to bring him news of his lands. That day was different though. I could see the bloodlust burning in Theodosius' eyes and I could tell that his tendency to revel in the blood of his foes had overcome him. With a single barked order, the lackeys cleared the room without even giving their reports and the senior legionaries were brought in to plan the coming battle.

The siege towers were arrayed in a great line to assault the entire length of the western wall simultaneously. Theodosius believed that his superiority in numbers would undoubtedly allow some Comitatenses to arrive on unmanned portions and from there take the enemy towers and flank the defenders.

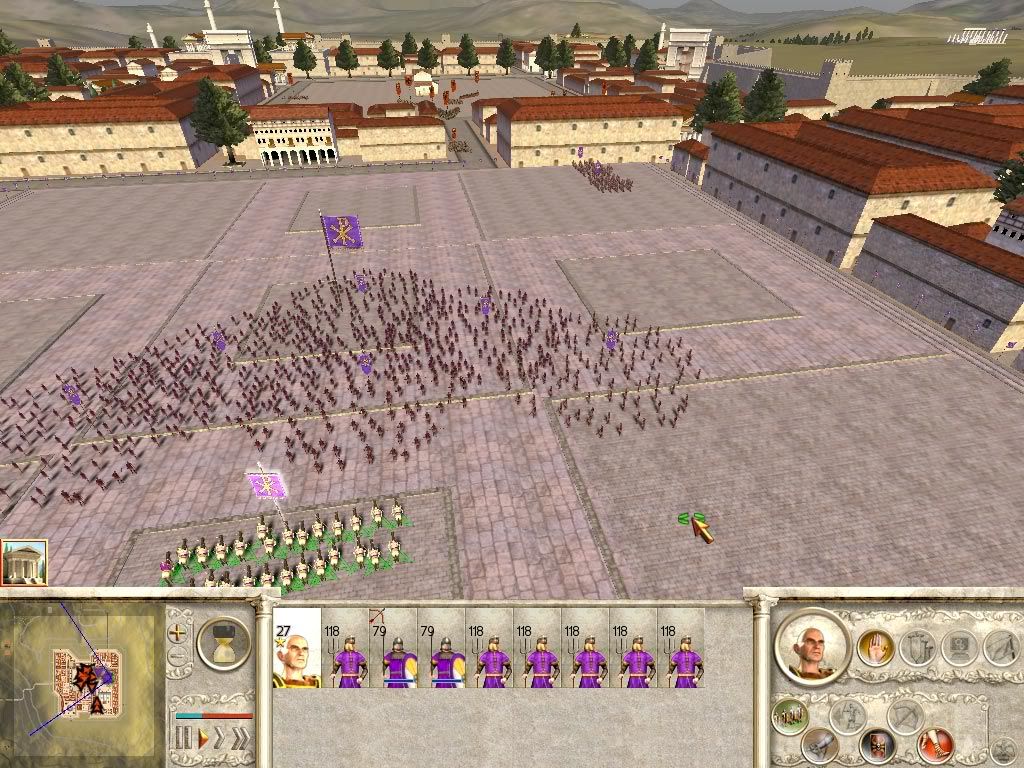

As the battle began, watchers reported the Sassanids had only poorly trained levies and a few groups of archers to hold their walls. Fire arrows rained down upon the advancing troops and the tower destined for the wall closest to the gatehouse was set aflame!

However, the remaining six towers reached the walls and disembarked their troops on the top.

Caught between highly trained Romans on both sides, the enemy bravely fought to the death, but to no purpose. The gatehouse was taken and the Sack of Ctesiphon began.

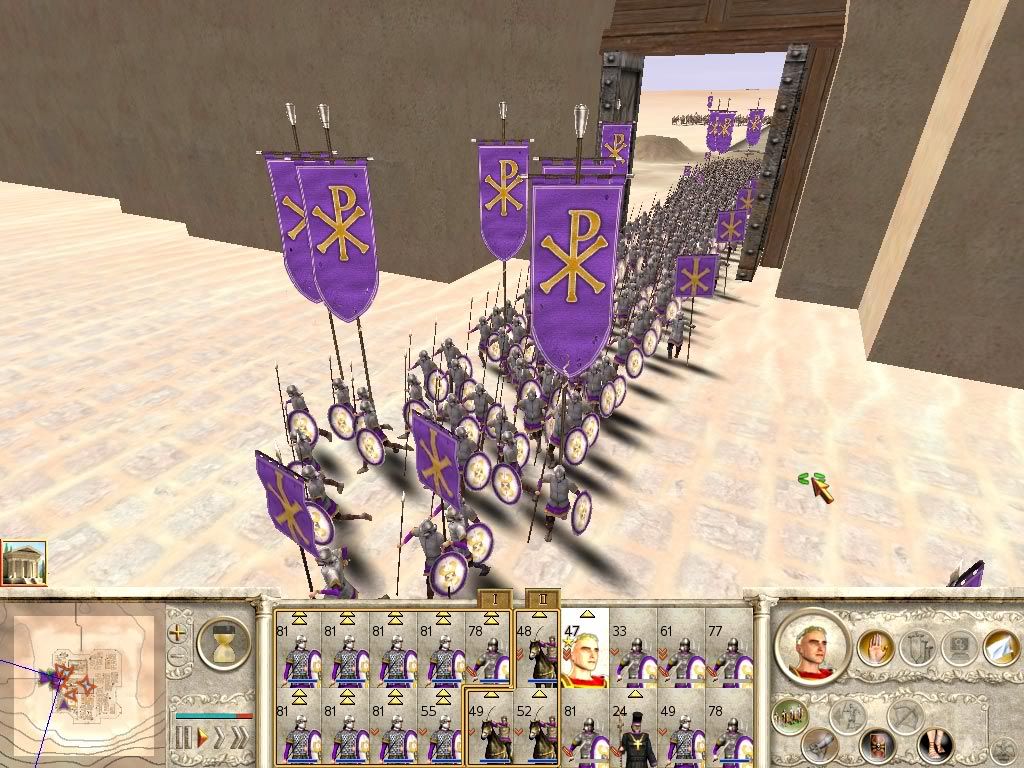

When Theodosius saw the banners of the Sassanid king fall from the walls and the doors to the city open, he let out a scream of bloodlust and ordered the massed spearmen into the city, himself following close behind with his bodyguards.

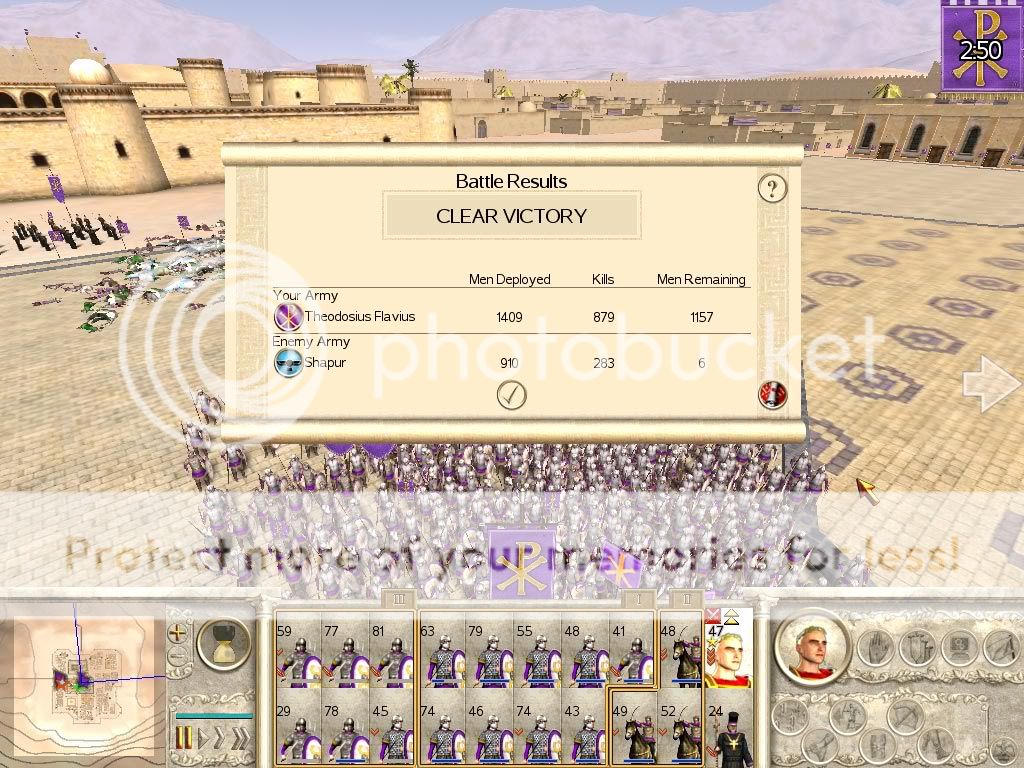

As the first spearmen entered the city streets, the Sassanid King Shapur tried vainly to stem the tide. His pathetic infantry were thrown back and his own bodyguard began to flee in panic. In the rush to escape from the mass of Roman steel, a single spear penetrated his armor, piercing his heart and throwing him from his horse.

Theodosius did not even pause at this momentous event, but pushed him men into the heart of the city to kill all who remained to oppose them. As he passed, I saw his men ride their horses directly over the corpse of the fallen king, crushing his body into a meaty pulp.

All discipline and order was lost and the troops went wild with blood, plunder and rapine. When dawn rose again over the Sassanid capital, two thirds of the population lay dead in the gutters and some 18,000 denarii worth of loot had been placed at the feet of Augustus Theodosius. That very afternoon, the burned and blood-splattered idols of the false gods were torn down and construction of a house of worship for the True Lord began. While some in the city whispered in dark alleys about this decision, the vast force occupying the city kept any from protesting the incident.

When the messengers from the previous morning were once again brought before Theodosius, they informed him that the Goths, had moved away from Sirmium and appeared to be returning to their homeland. As a reward for this good news, my master sent them away with vast amounts of gold to fund massive infrastructure and military improvements throughout the Empire. He then settled back to enjoy the comforts of Shapur's palace and to 'amuse' himself with the local populous while his army refitted and prepared to march north to Arsakia.

As the days past and it became obvious that the army would not be able to move until late in the following year, I fear my Emperor finally reached the limits of his patience. The palace was a primitive place in comparison to the luxury that existed in far away Constantinople and the dirty, dusty architecture of the city disgusted him. He took to viciously torturing enemy prisoners for entertainment and eventually turning to common citizens, abducted from their homes, when those ran short. From this time on the Emperor would be known, though only in dark rooms, as Theodosius the Cruel.

The sack of the city was prosperous for the Empire however and the funds had provided for the strengthening of the Harta Legion. The forces it would soon receive would allow it to eventually march north on Artaxarta, paralleling Augustus' own route to the newly named Sassanid capital of Arsakia. Messengers from the west confirmed the news from earlier in the year, that it seemed the Goths had indeed moved north of the Danube once again. The First and Second Danube Border Legions had resumed their posts at the east and west crossings and were once again holding the border of the western provinces.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks