This is a series of reports on my Cuman campaign (XL mod, Early, Hard, GA. However, my personal goal for the campaign is to keep the Cumans alive and existent as a contiguous nation by 1453 and thus defeat the tide of history – in two previous ‘learning’ campaigns, the Cumans were hammered into oblivion by the Mongol invasion upon the anvil of a powerful Byzantium or Egypt). I will present with a pseudo-historical narrative (because I enjoy that part of developing the game) with campaign notes for those who might be interested in playing the Cumans. The first half of this was posted on the Entrance Hall (up to Chagatai Khan).

The Tribal Confederation

Batu I succeeded his father at the age of 28 in 1087. The Cuman nation could barely be glorified with that description, being little more than loose, and ever shifting alliances of tribes. The previous khan had built a small fortification in Levidia on the Black Sea coast, but visiting Westerners would have to fight hard not to smile when anyone described it as a ‘keep’. The territory which the Cumans called home stretched over the wastes of Lesser Khazar to the east, and the mountainous provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia to the west. The Crimean peninsula, home to fishermen and little else, completed the homelands. These provinces were governed by men with no loyalty save to themselves and who could barely read or write.

Unlike his forebears, Batu had journeyed among the Western civilisations and had been held hostage by the Byzantine emperor during the recent alliance that had brought Wallachia under his father’s control. He had learned some letters, and battle lore. But Batu Khan had no intention of remaining a Byzantine puppet king, waiting meekly till the emperor chose the moment of his nation’s oblivion. Whilst the east held some prospects of elbow room in the rebel held provinces, these were poor places indeed. The Cumans needed wealth before they could control their destiny. Surrounded as they were by expansionist eyes, protected only by their poverty, and that for only a few years at best, the steppe people had to have more money.

There were only two choices before him. The lands of Kiev or Carpathia. Attacking Kiev would bring down the Russians upon his head, and they had many borders to attack. Carpathia however, was ill-defended by the Hungarians, and held many riches in its mountains – copper, silver and above all – ironstone. Batu set in motion his plans.

Stripping the old governors of their titles, he appointed the few men he could find with education – and that he could trust. Lord Gostyata, now Duke of Crimea, was the best of these new men. Batu issued a decree that the old nomad ways were to be abandoned, and farming and forest clearance to be implemented in all provinces. He had watchtowers constructed along the Byzantine model he had seen and a fort built in the Crimea. He knew the civilised nobility of the west would expect appropriate ‘overtures’ and began the construction of a royal palace for the training and reception of emissaries. Lord Gostyata was made Chamberlain of the Khanate.

Campaign notes: The starting lands of the Cumans are very poor. They are also bordered on all sides by potential foes. Early expansion is a must and whilst the east is easy (Khazar and Georgia are bribable) only Georgia doesn’t add yet another border. Kiev is pretty heavily defended, and one shares a long series of borders with the Russians, so to start a war there will sap the strength of your armies.

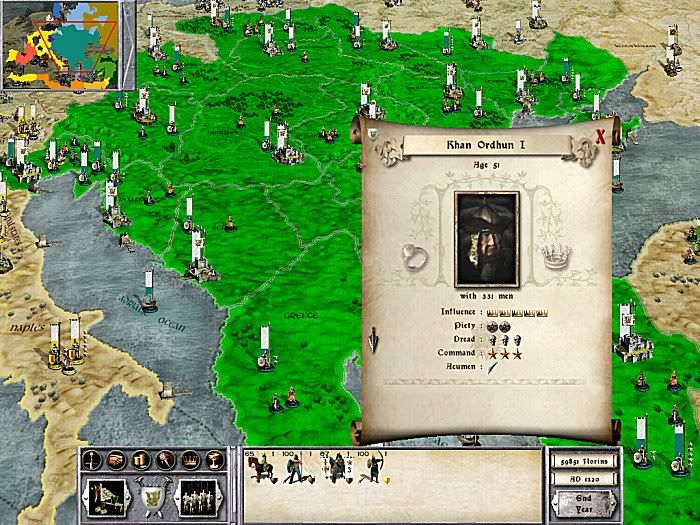

Generals are usually poor – rarely a star to share among them – and low acumen is the order of the day. This trend is hard to reverse until you get more influence for the Khan. You have a limited range of units, so you want to try and get to Bashkorts as soon as possible, then to build towards Steppe Heavy Cavalry and Cuman Heavy Cavalry – then to Cuman Warriors, which are the core of your armies.

After two previous eastern expansions, I decided to try the more historical trek west – as nomad steppe armies did for thousands of years. Since you don’t start with a royal palace, getting emissaries is an important goal.

Into the Mountains

Over the next few years, Batu built armies in Levidia to protect the homelands and invade Carpathia. He sought an alliance with the Poles, which was rejected, but emissaries from the Turks and Sicilians sought him out. In 1096, his eldest son, also Batu, a proud and clever young warrior waited at the Carpathian border for the signal. To disguise the preparations, he combined the activity with his wedding to Princess Elena of Russia. This alliance, carefully negotiated, protected the whole northern border of the homelands. Conveniently, the massing of warriors on their border also looked to the Hungarians like an army review for the newly-weds. As summer waned, Prince Batu launched into the Carpathian mountains. The Hungarians, caught utterly unawares, fled into Hungary proper.

Batu Khan knew that the proud Hungarian king would not let his rich province go without a fight and so it proved. The battle of Carpathia, celebrated in song for a thousand years, was about to commence.

Prince Batu’s army consisted of three units of bashkorts, one of unreliable slav infantry, two of peasant archers, and two units of unarmoured spearmen – though oddly, over three quarters of one of these spears had gone missing during the unopposed march into Carpathia. A unit of steppe cavalry complemented his own armoured heavy Cuman cavalry. All the Cumans were untested, and he himself was untried but was known to have excelled in his studies (4-star). But the true tutor of war was death and the dealing of death on the battlefield.

The very next year, a huge Hungarian army marched back into Carpathia, over 1750 men strong. Batu was outnumbered more than 2 to 1, but he knew the odds meant little – the Carpathian mountains gave him the edge in defence. As the morning of the battle dawned, the sky was grey and leaden. Prince Batu deployed on the side of a steep hill that bordered a rocky valley and anchored his left flank into the forest that crowned the hill. Here lay the trembling slavs, their morale encouraged by fierce bashkorts behind them. Years later, the old men of the slavs would tell their grandchildren that they were sure the Cuman bashkorts would as readily have hurled their vicious javelins into their allies’ backs as let them run from the enemy. The Hungarians seemed much the lesser evil!

Spearmen and bashkorts made a long defensive line along the hill. Behind them stood archers, high on the ridge to shoot over the spearmen’s heads. The steppe cavalry hid on the far left flank within the woods. In an unorthodox and risky move, Batu placed the other unit of archers on a ridge in the valley, given scant protection by the rump unit of spears. This was a bait – or as some muttered darkly, a suicide mission. His own cavalry anchored the right flank.

As the army settled into its positions, the clouds glowered lower in the sky and black rain drenched them. The gods were evidently displeased, for the crucial archers would be rendered useless as their bowstrings stretched. But as the first enemy banners were glimpsed cresting the far hills through the fog, the gods relented and the clouds lifted.

The Hungarians had brought armoured spearmen and many units of horse archers. As the air cleared, Batu could also make out that half their army were slav infantry – not quite as worrying. A unit of horse archers charged ahead and tried to get in range. Just as they outpaced their troops and settled ready to shoot, the Cuman steppe cavalry charged from their hiding place and swept across the battlefield. The first sight the climbing Hungarian army saw as they puffed up the steep approach was their horse archers screaming for mercy and fleeing for the valley escape. The Cumans watched with satisfaction.

But now was time for the hard work. The Hungarian general was clearly anxious to get this over with – perhaps his king had been harsh over his earlier abandonment of the province. Whatever, his entire infantry marched straight up the hill, save for a unit of horse archers and three of feudal sergeants which charged straight for the isolated archers. The archers loosed their hail of death and then ran for the lines to take up their planned positions. As the tiring sergeants turned to chase them, the steppe cavalry who were now hiding in the woods on Batu’s far right flank after disposing of the first horse archers, charged down the hill into their rear. The Hungarians tried to turn and defend. Prince Batu then took the opportunity to charge with his heavy cavalry into the disordered infantry.

On his left flank, the puffing Hungarian spearmen engaged the entire Cuman line. The line held, but only just. The Hungarian general clearly thought it was ripe for a killer blow and charged his royal knights at the rightmost bashkorts. He had never encountered these strange, half-naked, wild men before. In addition, charging uphill was not the best idea he had ever had – it was however, his last idea. With the advantage of height, the bashkort storm of javelins hit just as the cavalry closed and wiped three-quarters of them out. The other astonished knights then died on the wild men’s spears. After the battle, the Hungarian general’s face had a look of utter amazement frozen into his death mask.

The Hungarians wavered when their general fell in full view. Their approaching reinforcements were being shredded by arrows from the high hill. Just then, the feudal sergeants on the right lost their will to keep dying to Batu’s cavalry, and ran. Already soaked with blood, Batu wheeled and charged his men into the trembling flank of the armoured spearmen across the valley. They broke and the entire Hungarian line peeled away like burnt skin. The steppe cavalry tore into the rear of some horse archers that were trying to support the centre. They too ran and the entire army routed for home.

All that was left was to chase them to their graves, and several hundred were hacked down on the long scramble for safety. Though the victory was in sight, Prince Batu had the hundreds of prisoners taken swiftly executed – he had no wish to face the same men next year and it was wise that the Hungarian king understood right away that this struggle was life and death to the Cumans.

It was an emphatic victory, though Prince Batu became known as a man with scant mercy and men feared being captured by him even more than facing him in battle. More than three times as many Hungarians had died than Cumans – though the Cuman army was more damaged than would be wished for. Nonetheless, the army was blooded, and each unit increased in reputation, experience and valour.

As it turned out, the following years justified Batu’s cruelty. The Hungarians refused an offer for ceasefire, but they dared not try again to visit the killing fields of their former province.

By the turn of the century in 1100, Carpathia was securely a part of the Cuman homeland.

Campaign Notes: The Bashkort is your best unit for a long time. Apart from vanilla spears and slav warriors, they are the only spear unit you can build in Early and High. In early you should mix with normal spearmen as they won’t be armoured enough to stand on their own and have no rank bonuses. They’re a bit of a mob! They combine javelins with acting as good spears and are murderous to early armoured horse – indeed most early armour suffers. However, they must IMO be deployed with height for full effect. Use the horse (archers or light cav) to bring the enemy to your core. When you can get Cuman Warriors (AP archers and effective swordsmen) the combination of the two units is very good. You must, as the centuries wear on, get them armoured up and valoured up as later catholic units will give them trouble. I’m still learning to use steppe cavalry effectively – they are very fast and wonderful for crushing routers, but die far too easily. Luckily, most of your potential opponents use a lot of horse archers early on and as you know, simply glaring at them produces a rout.

The Winter of the Three Caskets

The first decade of the 1100s saw the Byzantine empire begin to crumble under the assaults of the Turks and Egyptians. Khan Batu accepted an alliance with the Emperor to secure his southern border whilst consolidating his gains. Those Magyars that refused to accept the Khan’s rule were put to hard labour in the deepening mines of Carpathia.

In 1110, the Lithuanians appeared on Batu’s borders as they invaded Chernigov. At his daughter-in-law’s urging, the Khan sent a force into Chernigov to help repel the newcomers alongside the Russian defenders. After a short and fierce engagement, the Russian border was again restored and the north quietened.

But the kingdom was still founded on shifting sand, as the economic situation was very tight. Farms were built and more forests cleared, as well as armouries and workshops built. Yet each year saw less and less money. Then, in 1119, Batu Khan died of a sudden illness.

Khan Batu II was a clever, witty man, not well versed in letters and often abrupt. His first act was to secure alliances once more with Novgorod and the Turkish sultan, and his second to celebrate the birth of a son, who he named Chagatai. He quickly dismissed some of his incompetent governors and promoted cleverer men. Trying to manage his finances more effectively, he started to disband older and costlier units. It all seemed so well thought out. In 1127, the khan even reduced taxes to celebrate the wedding of his brother to another Russian princess. The Russian Prince was most appreciative of this gesture as war with Novgorod had descended upon him.

The laughter in the royal yurts fell silent in 1130 as Batu II fell ill and died after only eleven years on the throne. His brother Subudai acceded, for Batu’s son was still a minor. In later years, many looked back and wished the young warrior had taken the throne regardless, for the Winter of the Three Caskets was upon the land. Subudai was harsher than his brother, and raised tax again. It was with his last breath, for he too died within the year. The third brother, Temudur, a man of great physical beauty and charisma, but avaricious and gluttonous tastes took the throne.

Temudur was no warrior, and the chaos and uncertainty of the khanate encouraged the treacherous Poles and Hungarians, who watching the disbanding of armies, desperate building of farms, and other signs of weakness, had made a compact upon a holy relic to invade Carpathia under the generalship of the brave Prince Casimir. The Alliance army was 2500 strong against the adept governor but unmilitary Lord Zoilus’ 974. They chose the depth of winter, which in the Carpathians is most severe, and many Cumans froze to death as they waited for the hammer to fall. Their bowstrings cracked and their catapults iced solid. It was not until the vast horde was upon them that they could even see their enemy in the blizzard. Carpathia was lost.

Yet so arrogant were the Poles that they had emptied two provinces of all but a few old men, and so Temudur immediately counter attacked into Volhynia and Lesser Poland. This seemed to prompt Casimir to get it over with and he assaulted Carpathia castle – only to suffer a terrible defeat, losing three quarters of his army during a portentous thunderstorm. A relief force brought Carpathia back under the Khan’s writ, though the Alliance was spreading his forces too thin and he was forced to fall back from the Polish provinces and lost lightly defended Wallachia to the Hungarians. Worse, he discovered that his Russian allies, who had failed to come to his aid on the weakened Polish borders, were in truth sorely beset themselves by the People of Novgorod. As the Russian empire collapsed, Temudur (who had no particular love for the Russians unlike his brothers) allied instead with the north Rus. He hoped to strike at Kiev if the chance came, for the economy was as ill as the Russian kingdom.

In 1139 the gods finally tired of the sons of Batu I, and Temudur took the last of the three caskets. The age of fear, invasion and catastrophe was at an end. The golden reign of Chagatai the Great had begun.

Campaign Notes: I had to find ways of making money and given Batu II’s character, reducing the armies and building diplomatic ties seemed sensible. As it turned out, it was nearly fatal. Dropping taxes seemed necessary despite the squeeze, for governors and generals were coming out with truly awful vices. Cuman kings tend to have a lot of children in succeeding years, so the brother syndrome is often met – this early time was one of the worst, dropping influence and V&Vs really low.

The alliance between Hungary and Poland was a hammer blow. Useless generals and no money – encouraging combination! The winter battle in Carpathia was one of the worse conditions I have ever seen – thick blizzards and useless archers – and without bows, Cuman defence is doomed. Since the AI then assaulted the castle, with siege engines, I thought the game was up, but I was able to mount an unbelievable defence after the siege engines were shot up, and the Poles simply died in the crush at the gates.

I felt bad about cancelling the alliance with Russia (given the half Russian blood of my princes) but they had not aided me by troubling Poland and were clearly doomed. Interestingly, the career of my greatest diplomat Tobdun Menashe began in 1136 by negotiating a ceasefire with the Hungarians after the siege of Carpathia which immediately turned into an alliance. This was cancelled by the Magyars on the next turn for fighting with the Poles, but they turned from a mortal enemy into a quiet neighbour.

The Greatest Khan

Chagatai Khan succeeded to the Wolf-skin Throne in 1138 at the age of twenty—three. He married Maria of Russia the same year. He was a great warrior, powerfully built and charismatic. After producing three sons in as many years, he set about the careful rebuilding of the kingdom. Peace, even a short period, was a blessing to his people and he used his influence to keep other nations at bay, though the mortal struggle between Byzantium and the Turks was now at its apogee and all eyes were turned towards the east.

The Poles, however, still smouldered with anger and in 1146 attacked the homeland in Levidia. The Khan led an army to the border and the Poles quailed, leaving in a hurry. At his battle camp, disturbing reports reached Chagatai. His cousin Batu, who had thought to gain the throne, had begun to show signs of serious madness. The Khan sent physicians, but too late – Batu, who was convinced of an amorous affair with an elephant, took the whole army of Moldavia on an invasion of Lesser Poland as he believed that his beloved had been abducted there. The army was lost along with the lunatic, who at least had died bravely challenging the might of the Polish – who luckily for Cuman reputation, had not understood his demands for the release of the illusory pachyderm.

In 1160, Chagatai Khan set in motion the most risky and ambitious plan for the future of the kingdom. He abandoned the eastern homelands of Levidia, Crimea and Lesser Khazar, razing them to the ground and leaving only token garrisons. The khan led the entire army west to Carpathia and then into Hungary. The Hungarian king fled, and his kingdom dissolved into civil war. A rebel army stayed to defend their home, but was crushed. The growing reputation of the emissary Tobdun Menashe was enhanced when he bribed the rebels of Austria to join the Khan.

The treacherous Byzantines then invaded Moldavia and split the kingdom in two. Chagatai invaded their province of Bulgaria, but fell back and took Croatia. The Hungarians counter-attacked into Hungary from Serbia, but were beaten.

Chagatai the Great died in 1173 after 35 years on the throne.. He had transformed his people from a nervous eastern target into a Balkan power. In his last year, the Byzantine emperor himself offered the hand of his daughter to Chagatai’s son to seal a peace. A great general, a noble khan, we shall not see his like again.

Campaign Notes:For once, the Byzantine Empire was in disarray on my borders. The Turks and the Egyptians were actually attacking and winning. As you can guess, Batu, my only five star general went unhinged. For role-playing purposes, while he needed to die in battle (no assassins yet) I allowed him to take the army of Moldavia on his suicide mission which seriously weakened me – so I had a penalty to using game mechanics to rid me of a problem. The mad fool damn near won too! Mind you, Chagatai’s sons all compensated soon after – suddenly I had two five star and a six star general.

I decided that the only way to expand was to take the Hungarian lands – rich, two iron provinces and much more defensible. Whilst the GA conditions meant that losing the homelands was a penalty, I was more concerned with survival. In the event, the alliance with the People of Novgorod held and they never invaded the very lightly defended lands in the east – I only lost Moldavia to the Byzzies. I stripped all improvements from the lands as I was sure I would lose them – maybe this made them less attractive to invaders. A gamble that paid off!

Chagatai finished with 8 influence, 7 command and 5 acumen. His sons of course, all benefited as did the loyalty of the kingdom which meant (with a bit of judicious tax management) that the eastern provinces stayed loyal throughout being split away.

The Roots of Gold

Khan Subudai II was a very well-educated man (his father had seen to that) and a great general. He built to ensure the happiness of his people and defend their gains while they became used to their new, rich homelands. He watched as the Greek peninsula was ravaged by war between the Egyptians and the Byzantines, waiting for an opportunity to steal the wealthy lands of Greece.

In 1181 there was a shock. The lightly defended Crimea was invaded by a jihad from an unknown people, the Almohads. Astonishingly, the bashkort garrison inflicted so many casualties on the invaders by hiding in the trees and butchering their disordered cavalry, that the Crimea was easily taken back by forces from Levidia.

Prince Temudur, brother of the Khan and the kingdom’s greatest general invaded Wallachia to retake it from the Hungarians in 1185. After a brilliant outflanking manoeuvre brought him down from his strong hilltop position, the Hungarian king was killed by bashkorts and his faction passed into history.

Meanwhile, the Byzantine empire, pressed from all sides, fell into civil war. Tobdun Menashe raced to Constantinople and bribed the army there. A year later, Emperor Nicephorus IV treacherously betrayed his daughter and the alliance and invaded Levidia across the sea. Furious beyond belief, Subudai ordered the sack of Constantinople and after a thousand years of history, the heart of the Roman heirs was torn into rubble and burned flesh. Naught was left, not even the crows were able to feed.

The Emperor sought revenge by invading Carpathia. Though his kataphraktoi were fearsome, they died to the endless hail of arrows from the Cuman warriors as they puffed and struggled up the sheer hillsides of the Carpathian mountains. Bashkorts skewered the last few and the armoured steppe heavy cavalry rode down the archers from Trebizond. Levidia, proud and unsuppressed by the small Byzantine force, rose up in revolt and chased them from its shores. Temudur invaded Greece and added its wealth to the kingdom of his brother.

The only cloud now on Subudai’s horizon was the lack of an heir. Some say that after her father’s betrayal, he could not bring himself to bed his Byzantine wife. However, whether ‘twas from a vengeful rage, or because the sweet wine of victory brings reconciliation to the hardest heart, the queen bore a son in 1192, Subudai’s fifty-second year. Four more were to follow. In the same year, the noble general Salih as Salih, the outlander who had gifted Constantinople to his new khan invaded Moldavia and lay the restored province and reunited kingdom before the throne of his patron. He was rewarded with the Governorship of the city he had gifted, and set the task of rebuilding it as a Cuman province.

In 1203, perhaps as a result of the exertions that a new passion brings to an old man, Subudai II died, a worthy son of his illustrious father. Under his leadership, the Cumans had a kingdom that would be worthy of being named ‘Empire’. The task that fell to his brother Temudur was to defend it.

Campaign Notes: Cuman Warriors and Steppe Heavy Cavalry are now available and with Carpathia and Hungary having iron deposits, and armourers built, become quite powerful as they can join melee. The wars helped increase valour. I used Serbia, Hungary and Carpathia to build the bulk of my armies, specialising for bashkorts, cavalry and Cuman warriors when possible (though more cavalry units meant H&C spent most time with them). Austria was left reasonably alone as being a frontier province meant it was still a target. Greece started to build towards shipbuilding and strategic agents.

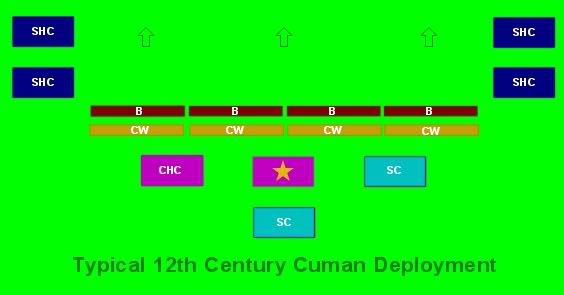

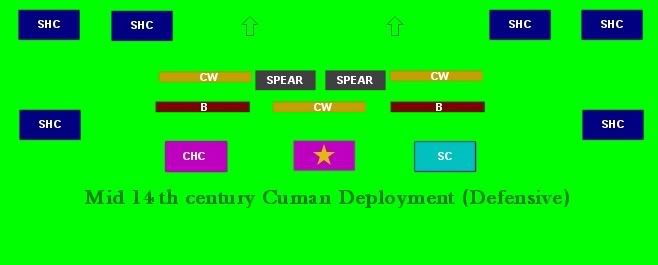

My standard army was now: Four units each of bashkorts and Cuman warriors. Four units of Steppe Heavy Cavalry, two units of Cuman Heavy Cavalry (usually the general’s unit as one) and two of Steppe Cavalry. This is powerful for defence or attack, but for attack I might replace a bashkort with SHC, and defence might lose a CHC for a CW. The Balkans are very defensible – all with serious hills and woods, absolutely ideal for this kind of army. The enemy trudges for a long way under a mobile hail of armour piercing arrows, chasing after shadows until it reaches a hill which showers it with death – javelins and arrows. Meanwhile, SHC sit behind them so the arrows come from everywhere. Even the best morale troops fail under this scenario – and if they need any encouragement, a flank attach by the katank look-alike CHC and the SHC from the rear provokes a serious discussion of the merits of becoming fertiliser for edelweiss. The incredibly fast Steppe Cavalry ensures that few get home to repent of their folly.

Talking of folly, in these situations the AI seems to favour an uphill charge by its mounted and armoured general who is always pin-cushioned by bashkort javelins.

Even if this army gets flanked, the Cuman warriors being serious swordsmen can stand against most units until bashkorts can get there. Armoured, high morale units can make a fight of things, and maybe in the later High and Late periods we will stop being able to fight on even terms.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks