From the deck of his ship, Posthumus Maenius watched the smoke collected in the sky over Athens. It would be there for days, trapped between the mountains and the coast; a reminder of all that he had lost.

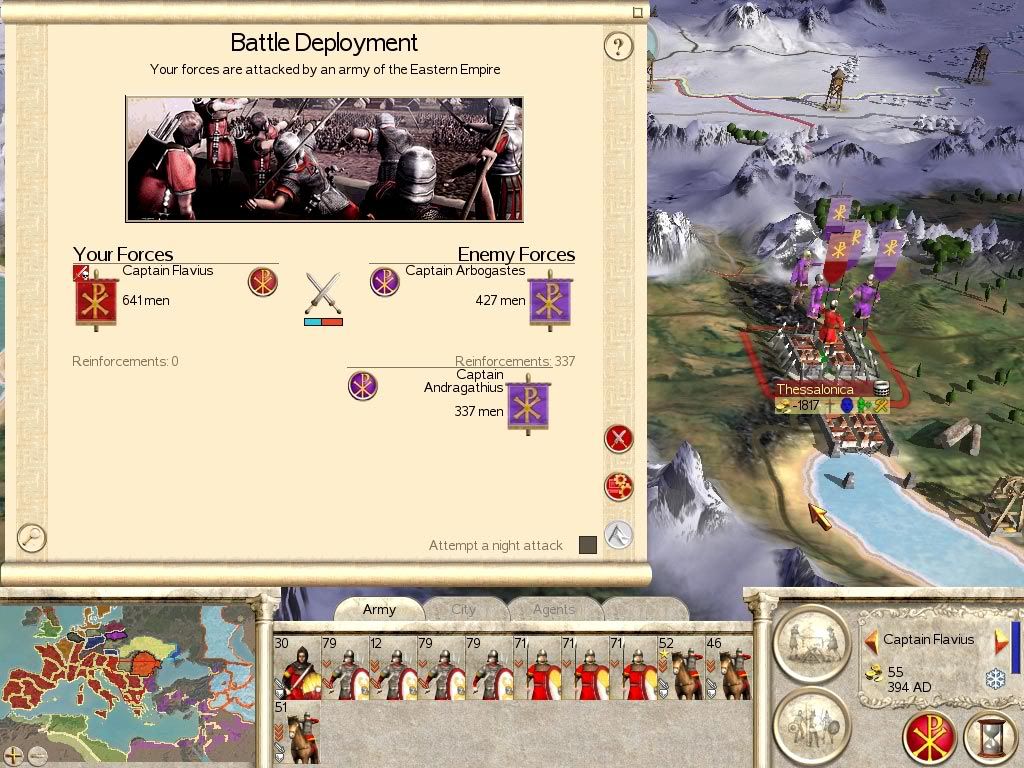

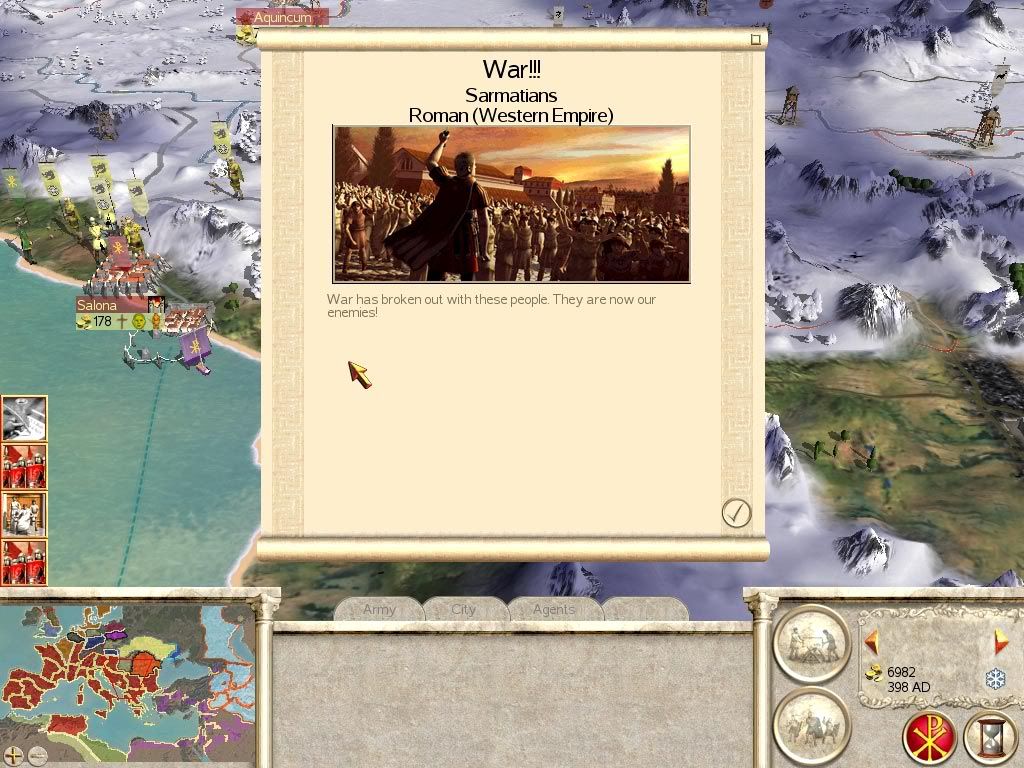

It had been only five years since his glorious destruction of the pride of the Western Empire. He had been celebrated as a hero by the plebeians and the patricians; all who had rejected the tyranny of Flavian rule and sought to create a better empire. They had been strong then. Though Thessalonica had been lost, they had still been strong. Carthage, North Africa, Sicily and Greece had remained under their control. Rich lands that had produced the means by which to take Rome itself. Nearly all gone now.

Only a year after the victory at Syracuse, word had come that Athens was under siege. If Greece fell, the recapture of Thessalonica would have been impossible and the wealth of the Balkans would have been closed to them for good. The city had to be saved and Posthumus had to be the one to do it. He controlled the largest army the rebels could field and he was also the only man alive who had beaten the enemy in open battle.

A fleet had been assembled and his men had departed, their spirits high. They had sailed into the Gulf of Corinth, so as to take the besieging army from the rear and smash it against the anvil of Athens’ great walls. They had found the situation exactly as they had expected it, though the circumstances had changed. Fisherman had told them that the city had actually fallen in 391 and been occupied by the enemy for a year and a half. Then the citizens had risen up and re-taken the city, under the leadership of a former centurion named Equitius Mamilius. The Flavians had evacuated the city in good order though and had immediately invested it, cutting off nearly all food supplies.

The situation had remained this way for almost a year and it appeared that Marcus’ dog, General Procopius Flavius, was nearing completion on the engines necessary to re-take the walls. Though the uprising had been popular, the enemy had left little behind in the way of arms and armor. Equitius had barely half the strength of his opponent, and much of that was mounted; he would have great difficulty holding the walls against massed Comitatenses. Posthumus had been forced to move immediately.

As the large Sicilian force disembarked, word came that the besiegers had disappeared. Their camp, their siege engines and their men… vanished, presumably into the Peloponnese. Posthumus had marched immediately for the city, to unite his forces with Equitius’ and then turn south to crush the enemy with their combined strength. The former centurian had opened the gates and brought his men out to meet their comrades. It was then that the trap had been sprung.

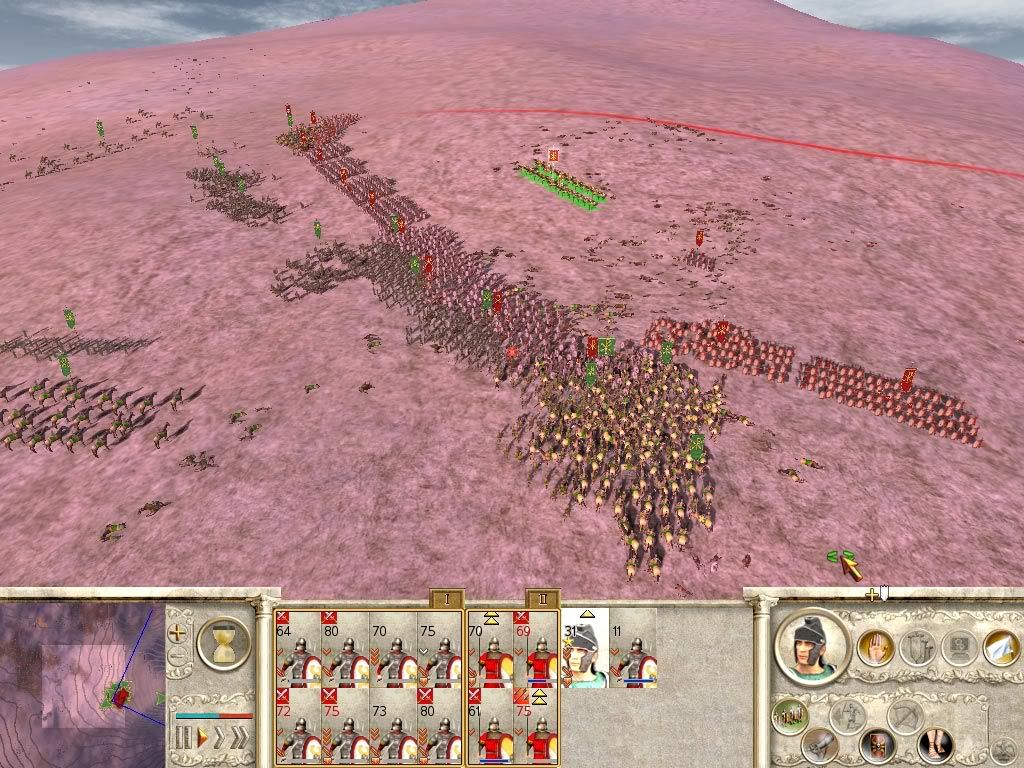

Procopius had not gone south, it seemed. Instead, he had hidden his legions in the shadow of a large hill west of the city. As Equitius’ men rode along its crest, unawares, the Flavians charged up it force.

The Athenian horse had wheeled wildly and charged them in a desperate attempt to push the enemy back down the hill. They had taken horrible losses.

Posthumus himself had been close enough to see this action and had at once pushed his men to the limit, moving them as fast as possible so as to aid their brethren.

They had not been fast enough though. The Athenians had been routed to great effect and the survivors had fled back to the city with barely half their strength. By the time the Sicilians had arrived, the enemy had reformed their lines at the crest of the hill.

A massive melee had erupted along the entire length of the armies.

For a while, it had appeared that they had gained the upper hand on the enemy’s left flank. Posthumus had personally led most of the reserve cavalry to this point to try and tip the balance. They had pushed deep into the red ranks and he had had the briefest glimpse of victory.

Then Procopius had committed his own reserve to the fight and had outflanked them.

His men fought bravely, but their losses soon became too great. As their right flank collapsed, the panic spread and soon the whole army was in flight.

Posthumus had tried desperately to rally them, but it had been hopeless. With his bodyguard entirely slain and his hopes smashed, he had barely managed to escape with his life. Procopius had personally chased him off the field and had nearly caught him.

The survivors had returned to the safety of the fleet in the Gulf of Corinth, but not even a quarter of the berths were occupied that evening.

Posthumus had drowned himself in wine, but sleep would not come to him. The next morning Athens fell.

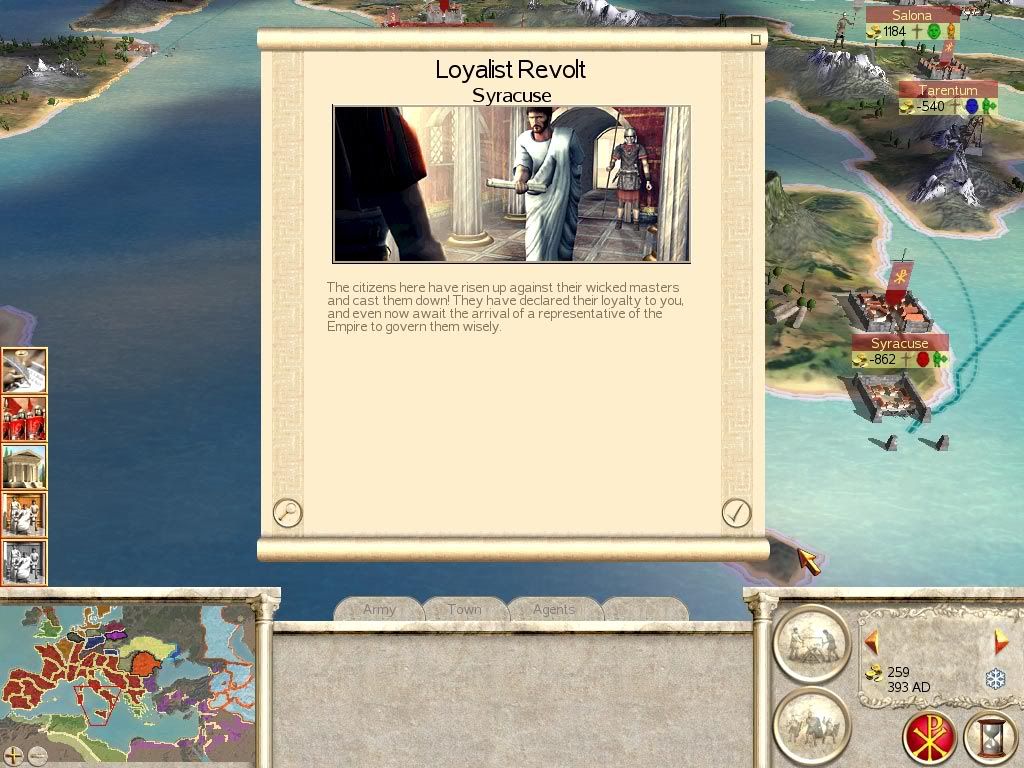

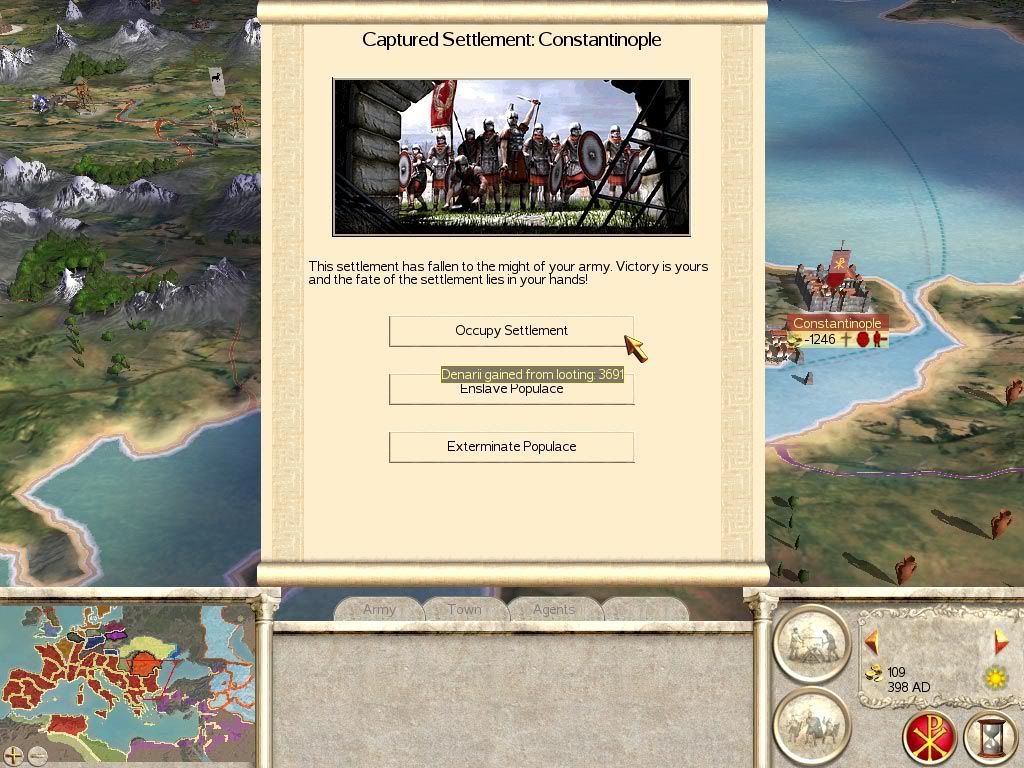

As if this had not been bad enough, news arrived the following week of a revolt in Syracuse. It seemed that the seeds of Christianity that Gallus Papinianus had sown had grown into an army. A Christian by the name of Spurius Cipius had plotted with many of the coverts to take the city. As the garrison slept, they had fallen upon them in their barracks, killing those who did not join them. By morning the city had been theirs and they had immediately declared loyalty to the Flavians.

Those who still worshipped the Old Gods had rioted violently, but they had been quelled when the full strength of the so-called African Legion had arrived to support the loyalists. Their general, a young Flavian named Maxentius, imposed harsh punishments on those who remained loyal to the rebellion and all hopes of another glorious uprising had been crushed.

Posthumus had remained at the bottom of a bottle for a month as his men similarly drowned their miseries on the fleet. The Flavians had practically no navy to speak of and they had been safe only a few hundred meters off shore. Eventually Posthumus had recovered his dignity had decided what to do next. Not all the news was bad. Athens still strained under the Flavian yoke and rioting had continued despite the second conquest of the city. In the north, Thessalonica had been assaulted by the Eastern Empire.

While the attack had failed, it was clear that the enemy’s position was not insurmountable. Their forces were limited, their supplies thin, and they were still surrounded by foes.

Using spies, Posthumus had managed to make contact with the new leader of the rebellious Greeks, a merchant named Libius Fundanus. Together, they had planned yet another uprising. This time, they would isolate and destroy the individual cohorts within the city, preventing them from escaping into the countryside where their full might could be unleashed. The plan might have succeeded had they not been betrayed. It seemed that Procopius had infiltrated the group with his own agents and they had warned him of what was planned. On the night of the attack they had found the barracks empty, the garrison gone.

When the sun rose the next morning, the Flavian forces stood in full battle array on a hill not far from the city. There was no doubt that they would invest the city again as soon as possible. Posthumus and Libius had agreed that they had no choice but to give battle and attempt to defeat them in the open. They did not have enough men to man the walls and the Flavians had proven themselves to be masters of siegecraft.

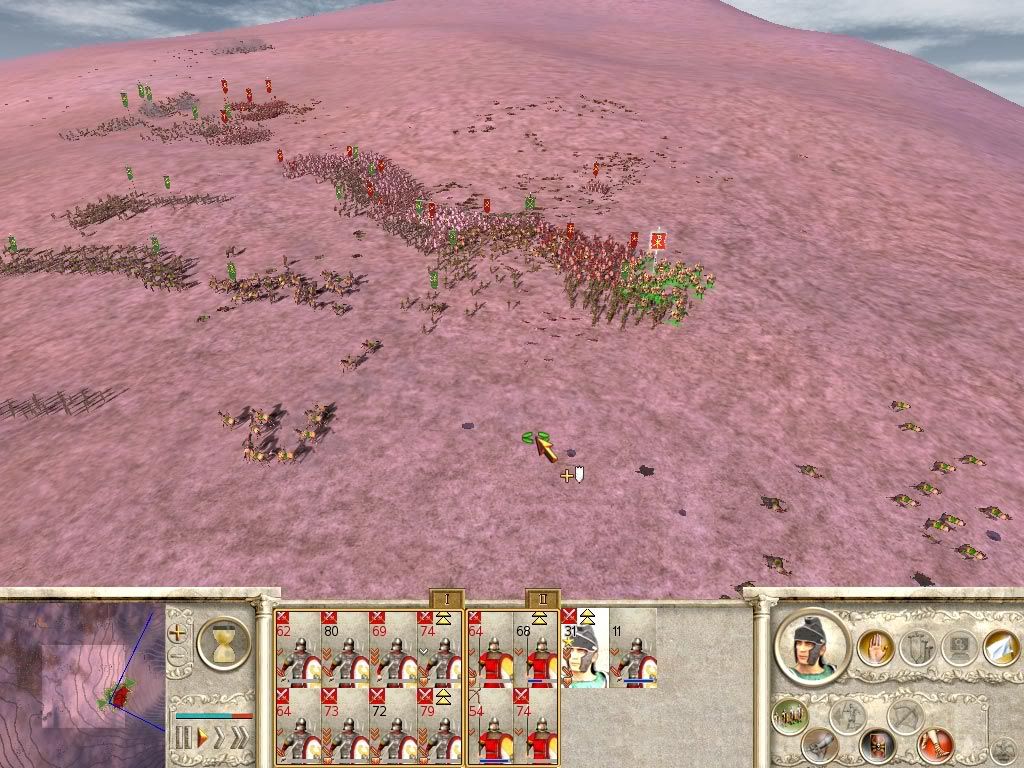

The attack had been glorious and desperate. The Flavians had drawn themselves up in a superb defensive position; on a hill with their left flank protected by a massive rock outcrop.

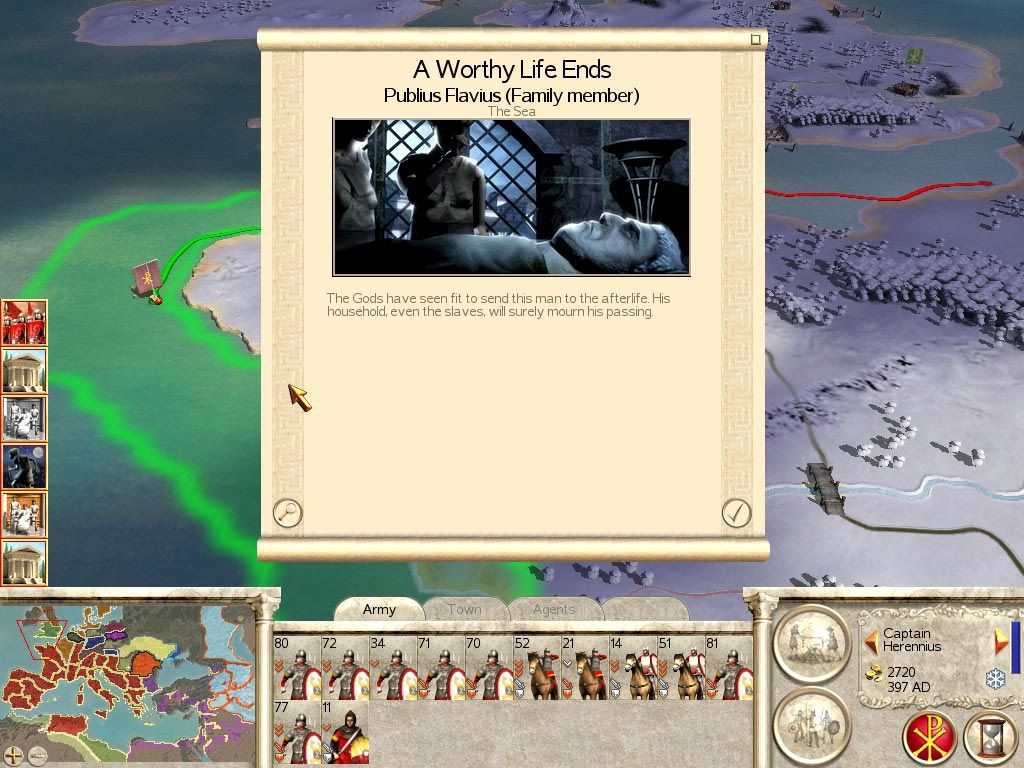

They had had no choice but to engage in a frontal assault. As in the previous battle, the melee had been intense. Unlike the previous battle, it had not been close. Libius had been killed quickly, trying to lead his men with an inspirational charge.

The Greeks and Sicilians had fought on, but it had been hopeless.

When the rout finally began, the butchery was unimaginable. Posthumus had charged at Procopius in desperation, hoping to be slain and thus saved the humiliation of yet another defeat. It was not to be though, his horse had panicked and run, denying him a glorious death in battle. When he finally arrived back at the fleet, he found less than fifty survivors waiting for him.

“Raise the anchor!”

The shout of the ship captain brought him out of his trance. Posthumus looked to the side and saw that most of the other ships had already begun to move off. Carthage. There was no where else to go. Athens had fallen within hours of battle. With no one left to man the gates, the Flavians had simply walked back in. He had no home, he had no army; he had failed.

Posthumus turned to a boy standing near him, “Bring me a jug of wine.” The child darted off without a word.

Hours later, the cliffs began to drop away and the great sea finally revealed itself to them.

“Ship ahead!”

Posthumus looked up. Squinting into the light of the sun low on the horizon, he could barely make out a blotch on the water. Slowly the ships formed into a defensive formation. After several minutes of silence, a friendly banner was spotted. Tension evaporated from the sailors and they returned to their normal duties. The ship had come alongside his within half an hour and a messenger had been rowed across.

Inside his cabin, the desperation on the man’s face told him all he needed to know. “For you sir,” the man said and held out a piece of parchment. Posthumus took it and read it.

“Leave me,” he said, speaking to the floor.

The man did and the hero of the rebellion sat alone in silence. He looked at his sword, lying on the table to his right. It would be so easy to end it all now. Had not Cato the Younger done just that when he had lost all? Posthumus dropped his eyes back to the floor. He knew he could not. His horse, yes… his horse had run from the last battle. That was what he had told himself every night since. Yet he knew it was not true. His spirit had been broken, but he was still afraid of dying.

He raised his eyes and stared at the sword. He gazed blankly at it for a long time before his eyes shifted to the jug standing beside it. As he stood and walked over to it, the parchment fell from his hand. It fluttered faintly as it settled on the floor of the cabin. As the light of the dying sun fell on it, two words stood out from the rest.

“…Carthage… …lost…”

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks