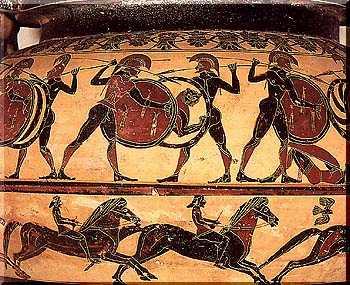

I found a website that makes a powerful arguement stating that overarm spears were not plausible in the anicent world:

http://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/nikolas.l...ons/spear.html

"There are many writers who insist that spears were used over-arm. I believe these writers to be wrong. The pictorial evidence is very poor. Where spears are shown to be used over-arm, it seems that this is for dramatic effect rather than for authenticity. Archaeology will tell us nothing on this issue, and I have come across no written record from antiquity which strongly backs up the over-arm theory. I shall now present my case for the under-arm use of spears.

The two competing handholds are as follows:

1. Over-arm: the spear is held in the centre, with the right hand. The hand is held at about head-height, with the elbow of the right arm out to the side. The right thumb of the user is on the head-side of his hand, and his four fingers curl over the top of the spear.

2. Under-arm: the spear is held in the right hand, with the thumb on the top of the spear and the spear held typically at around waist height. The fingers curl under the spear shaft. The spear shaft rests along the underside of the forearm with the butt-spike by the right elbow.

With the over-arm hold, the spear is held in the centre. This means that half the length of the spear is wasted, and serves merely as a counter-weight to the front half. No man would be strong enough to hold a spear horizontally over-arm by one end. This goes dead against the whole idea of a spear. A spear is a device for keeping your enemy at a distance. He cannot come close to hit you with a club or sword, because as he advances to his fighting distance, he gets skewered. An eight-foot spear is turned into a four-foot spear if it is held over-arm. If two formations of spearmen clashed, one using spears underarm, the other over-arm, then the fools using their spears over-arm would face their enemies’ spears before they themselves were in striking range.

With the over-arm hold, the rear end of the spear acts as a counterweight to the front end. If a foe were to strike the spearhead sideways with a sword, then the counterweight would act against the spear-user. The front end of the spear would act as a lever, twisting the wrist of the spearman, and the swinging rear counter-weight end would act to exaggerate this effect. To close with a spearman, a sword user has to knock the spearhead aside and rush in at his foe. The over-arm grip would make this enormously more easy. With an under-arm grip, the spearman has his spear braced along his forearm, and has much more control of the spearhead. The spearhead may be knocked aside, but it will resume position a great deal more quickly. If a high thrust over a shield is wanted, this can be achieved by bringing the right elbow up to shoulder height. Also, if the swordsman advances, then the under-arm spear user can retreat a great deal faster, to bring his spearhead between them, as he has the ability denied to the over-arm user, of pulling back his spear, and sliding his right hand up the shaft, to shorten the weapon for close use.

With the under-arm grip, a spearman can thrust with his spear downwards at the feet of his foe, or upward at his face. The strongest thrust he can do it at waist height, and he can disguise his intentions easily. He can hold his shield in position during all of this. Using an over-arm grip, the feet of the foe are out of reach. Greaves, protection for the lower leg, were very common in the ancient world, being part of the standard hoplite panoply. This suggests that the lower leg was a common target. Not only are the feet out of reach, but the thighs are difficult targets. A thrust at waist height is difficult, and the spear point will be travelling downwards, and will glance of a shield more easily. The only really strong thrust will be at the face and neck of the enemy. The neck was seldom armoured in ancient times. Greeks and Romans usually had no armour there at all. This thrust will be easy to see coming. Worse still, the spearman thrusting over-arm will of necessity expose himself as he does this, leaning forwards out of formation, and turning his shield to the left to give himself room for the thrust. If an enemy spearman to the right of the over-arm user saw the thrust coming, he would have an easy victim: a man who has stepped with his weight onto his front foot (thus preventing any evasion by footwork) with an exposed shieldless side.

As I mentioned, most ancient spears had butt-spikes, and spears were used in large formations. An under-arm grip allows the butt-spike to be controlled, tucked away where it will do no one any harm. Anyone standing behind an over-arm spearman will be faced with a butt-spike going in and out at every thrust, and unpredictably sideways whenever an enemy knocks the spearhead. If spears were use over-arm, then a lot of people would have had somebody’s eye out by mistake. "

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

That's just my suspicious hillbilly nature though I'm sure. It doesn't mean he's wrong - but anyone who posts long essays on their own theories of evolution, poetry, theories on the use of ancient weapons (which contradict the overwhelming majority of scholarship and modern opinion on the topic), movies they have made, methods of spotting kung-fu charlatans, board games he's invented, etc. seems to be stretching things a bit thin.

That's just my suspicious hillbilly nature though I'm sure. It doesn't mean he's wrong - but anyone who posts long essays on their own theories of evolution, poetry, theories on the use of ancient weapons (which contradict the overwhelming majority of scholarship and modern opinion on the topic), movies they have made, methods of spotting kung-fu charlatans, board games he's invented, etc. seems to be stretching things a bit thin.

Bookmarks