Org Mobile Site

This is a tough one, as the written history of this great subject is tainted with much 'coloring', so to speak.

I want to state that I have no predilection of Sweden over Poland/Lithuania, nor do I have an agenda; I just feel that the great Swedish monarch Gustaf II Adolf (Gustavus Adolphus) was one of history's greatest figures. But in this conflict he was not the outright winner, at least militarily. Let us take a look.

"Here strive God and the devil. If you hold with God, come over to me. If you prefer the devil, you will have to fight me first."

Gustavus Adolphus.

We do have a problem, one within the bounds of historical tradition, regarding the wars waged by Gustavus Adolphus (Gustaf II Adolf) against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1617-1629: the acute details of this war are indeed very nebulous. History is based on both truth and deception, and certainly colored by nationalism. But I will never believe that events can be thoroughly concocted. The war ended in a Swedish victory, but one of a political and economic nature, not a military one; tactical successes offset one another, and attrition bogged things down miserably. Thus it's easy for both sides to claim and denounce things, as nothing was inexorably decisive.

Sweden indeed had a standing army by the mid 1620s, but its population was possibly a fifth of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Among other things, Gustavus gave war a new look by altering the tactical doctrine of his cavalry. Whether his new cuirassiers galloped or sped at a trot (they perhaps galloped then trotted upon impact, as formation is more easily maintained at a trot), they achieved success when charging home, firing their pistols in a tight formation with cold steel, supported by infantry fire. In essence, they were often an effective battering ram. Swedish discipline became exemplary, religious duties strictly observed, and crime virtually non-existent. Gustavus Adolphus' actions during the Thirty Years War determined the political and religious balance of power in most of Europe at this time.

Before 1626, Gustavus' army was still basically, as he put it,

"My troops are poor Swedish and Finnish peasant followers, it's true, rude and ill-dressed; but they smile hard and they shall soon have better clothes."

Gustavus' army became a paradigm of one element from the classic military Byzantine manual, the Strategikon, written, according to tradition, by the emperor-general Flavius Maurikios Tiberius,

"Constant drill is of the greatest value to the soldier."

Gustavus formed military tactics centered around increased firepower, including mobile field artillery. His army was in peak form by 1631, and his system of cavalry charges, influenced by the Poles, initiated with pistol fire, integrated with infantry (pike and shot) and field artillery, supporting each other in self-sustaining combat groups, was the first time this had ever been seen in modern warfare. Much like Philip II of Macedon and Chinggis Khan in their day, Gustavus was a great forger of an army for his time. But perhaps more than any other great commander of history, his reforms touched on every area of military science, including the administrative and logistic branches.

But a topic of Gustavus' reforms must include the influence impressed upon him by the great Maurice of Nassau: the brilliant Dutch innovator and his staff created a military system of drill to train officers and soldiers, and began to move away from the dense column of the omnipotent tercio, developing a more extended and elastic formation. He equipped his cavalry with pistols and began to concentrate artillery pieces in batteries. Moreover, Maurice put supply, training, and pay on a regular basis. The tercio, an innovation for its time, was restructured to be smaller after the Battle of Rocroi in 1643, in which the stout tercios were blasted away by the maneuverability and superior firepower of Louis II de Bourbon (the Great Conde). But it was Maurice at Nieuwpoort (1600), then Gustavus at Breitenfeld (1631), who presaged that doom. Basically, Gustavus refined what Maurice did to a broader scale.

But things take time, and not without trial and error; Amrogio Spinola, another brilliant leader of this age, reversed this innovative trend for a while against the Dutch, and the Swedes, sans Gustavus, suffered a defeat at Nordlingen in 1634 against an army with the Spanish tercio on hand. But Johan Baner won victories thereafter.

The Swedish disasters at the hands of the Poles/Lithuanians at Kircholm (modern Salaspils, about twelve miles SE of Riga) and Klushino (Kluszyn) were in the past, and Gustavus would not let that happen again; no Swedish force would ever again be fooled by a feint to pull them out of a strong position (at least under him); his earthworks were not to 'hide' behind, in my opinion, but to provide security to fall back on if things went awry. This was sound war-making. It is opined by some that he waltzed into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth while their backs were turned, and easily captured towns to set up his entrenchments. But I am inclined to think the Baltic ports of Pilawa (Pilau) and Konigsberg (modern Kaliningrad) could not have been vulnerable to the degree it was child's play for the Swedes to take them, and there was also much diplomacy involved. They probably were defended by the trace italienne system. The town of Zamosc, for example, though further to the SE, saw the construction of new walls and seven bastions by 1602. But it seems quite accurate the Swedish onslaught in the 1620s initially made good progress because of an overall vulnerable scenario of the enemy. Dr. Geoffrey Parker, an expert on the Thirty Years War, wrote in his The Military Revolution, Pg 37,

"...Several outraged books and pamphlets were promptly written by Polish propagandists, excoriating the invaders for their 'unchivalrous deceit' in raising ramparts around their camps 'as though they needed a grave-digger's courage to conceal themselves', and deploring their painstaking siege techniques as kreta robota ('mole's work)'. But, mole's work or not, Crown Prince Wladislaw was immediately dispatched to the Netherlands to learn about these deceitful tactics at first hand. he was followed by Polish engineers, such as Adam Freitag who, in 1631, published at Leiden an international classic on developments in military fortification..."

This is from Richard Brzezinski, an authority on this chapter of history, who wrote a book on the Polish Hussars (possible red flag: Osprey Publishing),

"...if you take an UNBIASED (as in non-patriotic) view of Polish-Swedish actions from 1622 onwards through to the Great Northern War they are characterised by a consistent reluctance of the Poles to charge when the Swedish cavalry is deployed in formal battle-order backed by their infantry and artillery firepower. Take away the fire support, and the hussars are far less hesistant, and generally victorious..."

That may not be completely true, as some husaria did penetrate Swedish musketry formations at the battle of Mitawa (Mitau, modern Jelgava) in 1622, and again at Gorzno (Gurzno) in 1629 - but only initially; the threats were quickly closed. Excellent details are provided by experts on Zagloba's Tavern. Radoslaw Sikora, who denounces Brzezinski, and is a prime source for this topic, is working to right what he thinks are wrongs etc. He provides figures from the Polish army register, and Daniel Staberg, the Swedish expert, gives figures from some battle draws by Gustavus himself. But Sikora writes something peculiar, on the topic of the Polish husaria fighting Swedish regiments of musketeers,

"...Unfortunately I noticed that this selective and partial treatment of primary sources appear in Richard Brzezinski's work quite often. It is most apparent in the quoted descriptions of the hussaria fighting against the Swedish army (Kokenhausen, Mitawa/Mitau or Tczew/Dirschau). Anyone who knows what truly happened there grabs his head when reading how these battles are used to support false thesis of alleged considerable efficiency of firearms of the Swedish cavalry against the husaria."

What truly happened? Well, I feel one can admire something without it being a vice of 'partiality'. The battle of Mitawa was fought before Gustavus' efficient reforms took significant effect. Poland ultimately lost this war (I would say more on a political than military scale), and the husaria never defeated Gustavus (his tactical rebuff at Trzciana, in which he charged into an unwinnable situation to protect his infantry, notwithstanding). Koknese was a Swedish victory, and Gustavus clearly overcame the husaria at Gniew (Mewe) and Tczew (Dirschau), via method. Sikora's opinion as to why the Sejm (Polish diet) acquiesced to favorable terms for Sweden in 1629, if they were not losing the military aspect of this war (as some Polish apologists believe) - one in which he compares the feeling of the people of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to that of the American people in regards to Vietnam (late 1960s/early 1970s) is incredulous. Perhaps I am misconstruing him, but Polish soldiers were fighting in their own land against an invader. I am the last poster who wishes to insult people, and Mr. Sikora, clearly a civil and intelligent man, is invaluable for providing much trivia for this period.

From a political standpoint, the death of Gustavus amid the fog at Lutzen, a month before his 38th birthday, was a disaster. Looking back, perhaps we can blame him for that element of his leadership of heroic self-indulgence. But his death removed the one man who seemingly was capable of imposing an end to the fighting. Instead, the Thirty Years War dragged on for sixteen more years, witnessing hellish circumstances of disorganized and impoverished conditions. As the Dutch philosopher Hugo Grotius, who paid much attention to the concept of 'humane' warfare, tells us,

"...I saw prevailing throughout Europe a licence in making war of which even barbarous nations would have been ashamed..."

Gustavus Adolphus' War in Livonia and Polish Prussia 1617-1629

I have done the best I can to present a balanced view of this conflict (I am still a student with opinions); modern works which are very helpful are from Michael Roberts, Robert I. Frost, Ulf Sundberg, Richard Brzezinski, Radoslaw Sikora and Daniel Staberg. This site is invaluable for our topic:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/zaglobastavern/messages/1

The correspondence between Sikora and Staberg is exemplary, both for scholarship and amicableness.

Many of Gustavus' detractors (or some who are simply indifferent), perhaps mostly German and Polish Catholics etc., have the right to view him as a master propogandist. But in his mind he justified himself in terms of contemporary ideals, and plotted each move with the care of a diamond cutter. He was a champion of his cause, but dobtless a Realpolitiker as well. They all are!

The campaigns fought by Gustavus in Livonia and Polish Prussia between 1617 and 1629 receive comparitively little attention. This disappoints me, as the substantial military reforms of Gustavus were surely influenced by the fact that the superior Polish-Lithuanian cavalry, most notably the vaunted husaria (plural for hussar, or husarz), the crack heavy Polish cavalry, fighting with support from the medium/light cavalry, the Cossack (kozacy) horsemen (this name would be later changed to pancerni in 1648, to distinguish them from rebellious ethnic Cossacks), could not be beaten at this time in the early 17th century, at least in an open area, without utilizing combined arms and terrain not conducive to their style, which would diminish their ability to fight to the degree that ensured them victory. These great Polish cavalrymen were as light as most classified 'light' cavalrymen, but could strike in concentration with their 15 ft.+ lances at the gallop (perhaps longer, to outreach enemy pikes)! They could carry their charge through the enemy ranks. This tactical asset was one result of the organizing skills of Stefan Batory (d. 1586).

Gustavus never tactically overwhelmed the Poles, but he certainly got the better of them, except for one substantial time - when he was caught in a manner he painstakingly tried to avoid. It is not accurate, from my view, when claimed by some that he was 'crushed' by the Poles. But minor defeats of his cavalry, particularly units caught out in the open, by Polish cavalry are what affected some of his theories, reforms, and practices, which were realized throughout his later, more famous campaign.

Gustavus' father, duke Karl (Charles) IX of Sweden (king as of 1604), ousted Catholic officials, and repulsed an incursion into Sweden by Sigismund (Zygmunt) III at Stangebro (near modern Linkoping) in 1598. Sigismund III, officially crowned as the Swedish king in 1594, but reluctant to accept Protestantism as the state religion, desired to establish a permanent union between Sweden and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but instead created hostilities which led to intermittent war between the two nations lasting until 1721 (if we include up to the fall of Karl (Charles) XII). Charles was, however, unsuccessful when he invaded Livonia in 1600; his army was smashed by Jan Chodkiewicz's cavalry, of which about a third was the husaria, at Kircholm in 1605. Another army of 30,000 Muscovites under Dmitry Shuisky, supported by approx. 5,000 Swedish mercenaries (probably more so Scottish and German) under Jakob De la Gardie, was defeated five years later at Klushino by a much smaller Polish army, again with the ferocious husaria proving to be too strong. But Sweden's power was rising in the Baltic, as her fleet appeared outside Danzig (modern Gdansk) and Riga, capturing and searching ships trading with these prominent ports. Due to Danzig's neutral status at this time, the Swedes were able to provision their troops in Livonia from there. Aging and overwrought, Karl IX died in October, 1611, while war with Christian IV of Denmark, known as the Kalmar War, which broke out the previous April, was looking bad for Sweden. As a ruler, Karl IX, basically a practical man, was the link between his great father Gustavus Vasa and his even greater son. The Vasa kings in the 16th century laid the foundation of a national regular army. Gustavus perfected it.

At sixteen years of age, Gustavus Adolphus inherited the wars his father began, and only by exerting himself to the utmost was he able to achieve peaceful settlements with Denmark (Treaty of Knarod, January, 1613) and Russia (Treaty of Stolbova, February, 1617). He had to restrict himself due to the terms involving indemnity with Denmark, but his treaty with Russia altogether shut out Muscovy from the Baltic, and its trade became dependent on Sweden. It was clear that Gustavus would resolve to take up the struggle with the Poles in Livonia if necessary. The Sveriges Riksdag (Swedish parliament) consented to this in spite of financial concerns.

Hostilies had already begun in 1617, though a truce had been formally agreed upon in 1613 and prolonged for two years the following year. The king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sigismund III, whose unwavering claims to the throne of Sweden (by birth he was united along the royal lines of the Vasa and Jagiello) would involve Poland in a whole series of unprofitable wars with Sweden spanning 6 decades, instructed his government to not renew the truce. The Swedes captured Pernau (modern Parnu), and by the autumn of 1618 Gustavus was willing to arrange an armistice, but Sigismund III rejected every proposal in that course, keeping unflinchingly to his claim to be acknowledged King of Sweden. Finally a truce was arranged on September 23, 1618, and Jan Chodkiewicz, who had conducted himself with such esteem on the Livonian front, was sent against the Ottoman threat from the south. The great Polish hetman died in September of 1621, amid his successful entrenched defense against the sultan Osman II's huge invading army, perhaps numbering 100,000, at Khotyn (Chocim), in the Ukraine. During this time the rivalry between Gustavus and Sigismund III transposed into a very different and higher plane.

Another blow for the Poles was the death of Jan Zamoyski in 1605. It had been the firm conviction of this great szlachcic and magnate that Poland could not achieve any long term success against Sweden without a navy. But his efforts to prevail upon Danzig (modern Gdansk) to produce a fleet were in vain, as the neutral city didn't want to displease the Swedish sovereign at the time (among other reasons).

A Protestant coalition, including the Dutch Republic, Lubeck (the anchor of the Hansaetic League), and Sweden, was formed amongst the Northern countries, while Sigismund III fixed his attention on the Hapsburg monarchy, a land power firmly Catholic in its policy. An 'eternal' alliance, very vague in principle, was concluded. Sigismund III now geared his thoughts to far-reaching plans for winning Sweden back (he always believed Sweden was rightly his). Attacking Gustavus by propaganda in his own kingdom, he endeavored, with the help of Spain and other external enemies of Sweden, to create a constant menace to his adversary. Gustavus proposed peace, including the right for Sigismund III to use the title 'King of Sweden', but this was rejected. Gustavus then obtained from the Sveriges Riksdag the funds for renewing the war.

Essentially, Gustavus' war against Poland was for control of the Baltic coast. He viewed Catholic Poland as a threat to Protestantism - a threat that perhaps barely existed, but one he thought existed, and the Scandinavian monarchies certainly symbolized the pillars of Protestantism. It was very prudent on the part of Gustavus to form an alliance with Denmark in 1628 to defend Stralsund (NE Germany), as a divided Protestant Scandinavia would result in their defeat by the Catholic states. Like Danzig (modern Gdansk), Stralsund was a principal strategic base on the Baltic. Sigismund III, the son of the Swedish king John III (d. 1592) and Catherine Jagiellon (Katarzyna Jagiellonka, d. 1583), lost his title as the official Swedish king in 1599, deposed by the Sveriges Riksdag. His politics of support for Catholic Reformation (counterreformation) and personal ambition were among the reasons for the wars to come. This, of course, can be viewed in other ways by his apologists, which is totally understandable.

In 1617, Gustavus indeed took advantage of Poland's involvement with the Muscovites and Ottomans, gaining hegemony on the eastern Baltic in Livonia, compelling the Poles under Prince Krzysztof Radziwill to conclude an armistice until 1620. The Thirty Years War had begun two years earlier, and Gustavus clearly saw Sweden would be drawn into the vortex. He vainly tried to renew the truce with Poland, as Sigismund III, influenced by the Jesuits and feeling safe from the central and north-east with a newly agreed truce with Russia, could not be influenced. After thorough preparations, Gustavus sailed for the mouth of the Dvina (Duna) in July, 1621 with about 18,000 men aboard 76 ships. The fort commanding the mouth of the Dvina, Dynemunt (Dunamunde), was taken, and the siege of Riga began on August 13. Terms were refused by the garrison, which numbered 300 and supported by a citizen militia of 3,700. Gustavus was thus compelled to open a bombardment. On August 30, a small relief force under Radziwill, perhaps just 1,500 men, was beaten back; Swedish entrenchments were too firm and gunfire too solid to overcome, and Radziwill withdrew by August 31. After mining was resorted to, in which Gustavus threatened to explode all the mines at once, Riga surrendered on September 25, 1621. To isolate Poland even more from the sea, he marched south across the Dvina, took Mitawa (Mitau, modern Jelgava), and, leaving ravaged Livonia to its fate, stationed his troops in Courland. The conquest of Riga meant there was no longer any possibility for Poland to establish herself as a Baltic power. Through Riga passed a third of her exports. With it Gustavus gained political and strategic advantages and a base for equipping his fleet. At the same time, the Poles and Ottomans opened talks, and a mutual peace was agreed upon (for now).

The east part of Livonia and the important town of Dorpat remained, however, in Polish hands. In the autumn of 1622 both sides were again ready to accept an armistice. Gustavus was too eager for a truce to grudge Sigismund III the kingship of Sweden, so long as he did not call himself Hereditary King. Krzysztof Radziwill had advised Sigismund III to ask for an armistice, but, as usual, he hesitated to the very last. This gave Sweden's Chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, an opportunity to seperate the interests of Poland and Lithuania, and to offer the latter peace and neutrality in the struggle between Sweden and Poland. This was the first Swedish attempt to drive a wedge between the two halves of the Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy. But the plan did not succeed, and Gustavus personally conducted the campaign in the summer of 1622. Radziwill retook Mitawa, and a battle was fought on August 3, 1622. Initially, it seems Swedish infantrymen, positioned in thickets with swampy ground between them and the Lithuanians, fired upon the enemy, refusing to come out in the open, a condition which Radziwill proposed. The Swedes overwhelmed the outnumbered haiduks (mercenary foot-soldiers of mostly Magyar stock from Hungary) in an infantry clash. Some companies of husaria then displayed some recalcitrance, as there existed serious financial problems with the Lithuanian forces, which was more a private army than a state one at this time, which led to a lack of loyalty and morale amongst many. But two banners, perhaps about 400 husaria (numbers for these banners, more properly known as Choragiews, vary) did intrepidly charge into the Swedish ranks and, despite unfavorable ground, penetrated through with minimal loss (the Swedish army was not yet the drilled, disciplined force of a few years away, but vastly improving). The Swedes reinforced their positions which precluded the husaria from turning around (there was also no support for the husaria either). Radziwill built solid fortifications around Mitawa (Mitau) which precluded a resolved effort by the Swedes to recapture it by military means. But Radziwill was again forced to conclude an armistice, as adequate forces could not be sent to stop Gustavus from continuing his conquest, as the serious war with the Ottomans was too recent to not keep forces on the lookout further south. From a Swedish viewpoint, this establishment by Gustavus wiped away much of the shame caused by the disaster of the Battle of Kircholm sixteen years earlier, and Mitawa (Mitau) was occupied on October 3, 1622 by Gustavus. But so severe was the sickness which afflicted the Swedish forces that some 10,000 reinforcements had to be called. Renewed in November, 1622, the truce was prolonged year after year until 1625, though the sole object of each side was to gain time to prepare for more impending war.

A few years earlier Gustavus had found support in Brandenburg-Prussia, which might, under favorable conditions, become very useful. East Prussia had been inherited in 1619 by the Elector of Brandenburg, and his sister, Hedvig Eleonora, had married Gustavus in 1620. But the Elector Georg Wilhelm was himself afraid of Poland and not yet willing to comply immediately with the demands made by Gustavus, now his brother-in-law. Inactive and not willing to be decisive, Georg Wilhelm tried to avoid difficulties and therefore added an element of uncertainty to the political situation amongst the Northern countries. Sigismund III's phlegmatic temperamant had a similar effect, who carried a fear of losing the leading elements of Prussia into the arms of Sweden. For Gustavus, it was very important that Sigismund III didn't gain a firm footing in Ducal (East) Prussia.

When Gustavus renewed hostilities against Poland, it was partly for national reasons and partly to assist the German Protestants. During the preceding years, Sigismund III had constantly showed a desire to attack Sweden on a large scale, although the Polish Sejm at this time expressed no desire to support him and the funds at his disposal were insufficient. Two factors important for Gustavus were the change of James I of England's policy and his desire to arrange, with the help of Cardinal Richelieu of France, a coalition of Protestant powers against the Hapsburgs and their Catholic allies. Christian IV of Denmark, whose relations with Sweden had again, in the fall of 1623, been strained to the utmost, and with the support of England and the Dutch Republic, he led Protestant action against the Hapsburg coalition in Germany, and this at last made Gustavus feel safe with regard to Denmark. He would have preferred to land in Polish Prussia, but probably out of consideration for his brother-in-law and the Dutch, who grudged him Danzig (modern Gdansk), he resumed the struggle in Livonia. Gustavus' earlier strategic successes in 1621-1622 marked a shift in the balance of forces within the Baltic, and denied Sigismund III a port from which he could launch a legitimist invasion of Sweden, though he was fortunate he was able to establish this valuable footing here in Livonia and Courland scarcely opposed. But he did beat back the small relief force at Riga; he wouldn't have been able to take the city if he hadn't overcome this force, perhaps just 1,500 men; the garrison of Riga was very valiant in its defense, spurred by the hope for Radziwill to make some headway. Polish apologists stress the Ottoman threat as being more serious. While this is true for before the autumn of 1621, the Ottomans were repulsed (as I already mentioned) with great loss by Jan Chodkiewicz in September-October, 1621, at the fortress of Khotyn (Chocim), and internal strife soon broke amongst the janissaries, during which the sultan Osman II was murdered. A peace was agreed upon and the Polish/Lithuanian-Ottoman border would be fairly quiet until 1633. Gustavus was now seemingly the threat to be dealt with. But Stanislaw Koniecpolski, a superb commander, was busy dealing with the Tartars from 1624-1626, to the east.

A permanent peace could not be reached between Gustavus and Sigismund III to replace the existing truce, so Gustavus again arrived with his army at the mouth of the Dvina in May of 1625 with some 20,000 men aboard 148 ships, his army now in a rapidly-advancing phase of a newly forged instrument of war. His forces attacked at three points - (1) Courland, on the Baltic shore, taking the ports of Ventspils (Windau) and Liepaja (Libau), (2) Koknese (Kokenhausen), further inland, and (3) Dorpat (modern Tartu), to the north. No major field engagements occured, but Koknese was taken on July 15, 1625, followed by the castle of Birze (modern Birzai) a month later, after a valiant defense by the garrison. The attempt of a Polish colonel to retake Riga with 2,000 men was repulsed, and a second attempt by the Chancellor of Lithunia, Jan Stanislaw Sapieha, with 3,000 men (these figures are not confirmed) was driven off with a loss of all their guns. Around the same time, Dorpat was taken by Jakob De la Gardie, and in late September Mitawa was taken by Swedish forces. But Polish forces prevented Gusav Horn from capturing Dunaberg (modern Daugavpils). Gustavus would now resolve to take the initiative against enemy ground forces, concentrated to his south.

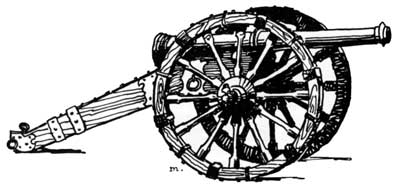

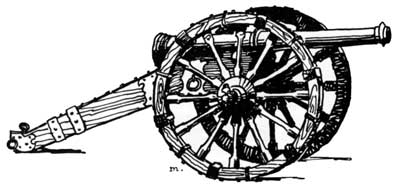

In 1624, Gustavus decreed a lighter design to replace the matchlock musket for standard issue - the wheel-lock pistol and musket, reputedly invented in 1517 by one Johann Kiefuss, a German gun maker from Nuremburg. These firearms did not entail a smoldering match, thus there would be no more stressing about it going out when precipitation rolls in, or the danger of handling gunpowder around the match. The idea of this mechanism is simple; think of a modern lighter which has a flint pressed up against a roughened little metal wheel - when the wheel is spun with your finger, the flint pressed against its surface throws off sparks. The same system was used in these firearms to create sparks as needed to ignite the gunpowder to fire the gun. It's all evolutionary. But it was more expensive: surely not everyone received the better design (dragoons must have been given priority, as they carried their muskets across the back in a leather strap. But even those of Gustavus' men retained the matchlock, they increasingly received lighter ones. By 1626, reloading speeds in Gustavus' army were improved to the point where three ranks of musketeers, reduced from six when all loaded, could simultaneously maintain a continuous barrage; his musketeers were trained to fire by salvo - the discharge of an entire unit's supply in one or two volleys to produce a wall of bullets, and they waited until their enemy was not more than a distance of 35-70 yards. Firepower was greatly increased by the addition of copiuos field artillery pieces. In 1626, the 3 lb. leather guns were introduced, the first regimental guns to fire fixed ammunition with wooden cases, and they could fire at a rate not much slower than a musketeer. It was named the 'leather gun' because the external casing (frame) of the barrel was made of leather. The bore (tube) of the gun was made of copper. Every effort was made to curtail weight, and without its comparitively light carriage, and the gun weighed 90 lbs. (about 400 lbs. including the carriage). The 'leather gun' could easily be manuevered on the battlefield by two men and one horse. It possessed the asset of mobility to the highest degree, and albeit it was a major technological development, it turned out to have a major drawback: the gun sacrificed too much to lightness and mobility, and upon repeated fire it became so hot that a new charge would often ignite spontaneously, which could lead to disaster amongst its crew, who could still be in the recoil path. Ultimately, the 'leather gun' was a failure as a regimental field piece, but certainly the advent of light mobile artillery in the field. Once Gustavus entered Germany in 1630, the 'leather gun' had been replaced by the 4 lb. Piece Suedoise, made of heavier substance, if slightly less mobile; a third man was required, along with two horses to handle it. This regimental gun was supreme, and could fire eight rounds of grapeshot to every six shots by a musketeer. This was possible because its design involved a new artillery cartridge, in which the shot and repellant charge were wired together to expedite holding. Moreover, a 9 lb. demiculverin, produced by Gustavus' bright young artillery chief, Lennart Torstensson, was introduced. This weapon was classed as the feildpeece - par excellence. The science of mobile field artillery (ie, movable amid battle) may be arguably said to have been first utilized substantially by Gustavus and his engineers. But we can always find precedents; in this case, Babur and Charles V of Spain identified the value of field guns.

The 4 lb. cast-iron regimental gun

The 4 lb. cast-iron regimental gun

In late 1625, Gustavus could be fairly sure of his ground. Sweden was more prepared for war than ever; the unity of king, ministry, noble class, and people was in marked contrast to the condition of any other European state. The ordinary soldiers were given a personal stake in their country, as Gustavus provided land as compensation for service, and for the officers, usually farms on crown lands, form which they collected rent from the tenant-farmer. When not on campaign, the soldier worked on these farms in exchange for board and lodging. I'll spare these details, but basically the soldiers of Sweden under Gustavus' reign became bound to the land, assisiting with its maintenance. Thus the civilian population was involved with the army and its support, and Gustavus was supported to utilize Swedish commerce and industry to fully subsidize the wars he would fight. Moreover, a system of regulated conscription and administration was established, in which each province raised regiments which were supported by local taxes. These provincial regiments would remain permanent. Also by 1625, the Sveriges Riksdag was operating on a regular annual budget with a reformed fiscal system. Drafts to supply men to the regular army were drawn from the militia, which was the home-defence force in which all able-bodied men over the age of fifteen were liable to serve. However, the population of Sweden was too small to provide all the soldiers Gustavus needed, once war thinned his ranks; after all, he would be fighting countries vastly outnumbering Sweden in population. This void was filled by soldiers of fortune (mercenaries), but not the cut-throat bands which ravaged central Europe; the professional mercenaries who fought for Gustavus accepted the stern discipline in return for treatment as good as that received by native Swedes. The Green Brigade (brigades in Gustavus' army were named after the color of their flags), composed mostly of Scottish soldiers, was among the finest units of the Thirty Years' War, and led by the likes of Robert Munro, John Hepburn, Alexander Leslie, and Donald Mackay.

To reiterate, Gustavus integrated the activity of lighter mobile artillery, cavalry, and infantry to a science which produced a radically different, balanced, and superior army than any other in Europe (probably anywhere at the time). Artillery was no longer an insitutional appendage, but a regimental branch of his balanced army. The Battle of Breitenfeld, fought on September 17, 1631, against the able Johann Tserclaes von Tilly, brilliantly realized the basic military theory of Gustavus - the superiority of mobility over weight (and combined arms), something the likes of Alexander and Hannibal showcased amid their triumphs from two millennia earlier. But now Gustavus applied the concept with the technology of his day. It took some time, and not without trial and error (he didn't turn field artillery into a battle-deciding arm, but a significant support to his cavalry and infantry in the field). But the heroic example of Gustavus' Alexandrian style of leadership would later cost him his life. Some may say he was too rash, but leading by personal example will do wonders for the moral of one's troops.

But the supreme army it became we was still in its developing stages in late 1625, where we left off the chronoligical narrative.

The Polish forces in the region of Wallmoja (Wallhof) probably numbered some 6-7,000 men, between Jan Sapieha (the son of the Lithuanian chancellor), Radziwill, and Aleksander Gosiewski. Marching swiftly SW from Koknese (Kokenhausen) to the region around Wallmoja (Wallhof), near Birze (modern Birzai), in a forced march with perhaps 3,000 picked men (2,000 Finnish Hakkapeliitat, plural for a Hakkapeliita, and about 1,000 musketeers), of over 30 miles in 36 hours in difficult terrain, Gustavus swiftly fell upon the larger force of about 4,000 (at most) under Sapieha and routed them in what B.H. Liddell Hart describes as perhaps the earliest example in modern military history of the principles of concentration, both strategical and tactical, and of the combination of fire and movement, which forms the burden of every military manual nowadays (Hart wrote this in 1927). Basically, he surprised the Polish-Lithuanian force in wooded terrain, which precluded them from outflanking his dispositions - a condition he effectuated, using his infantry in the woods to effect enfilading fire upon them. Now with complete control of Livonia, and the fortified line south of the Dvina no longer threatened, Gustavus wanted to make peace (albeit favorable to his position), and sent an embassy to Warsaw. But part of it was seized, and due to the difficulty to procure their release, peace was not in the cards. Jakob De la Gardie, who would later advocate peace with Poland, was left in Livonia to secure the Swedish position, and Gustavus returned to Stockholm.

Important note: Polish accounts claim Jan Sapieha's army was surprised in a non-fortified position with merely 1,500-2,000 men, and that the total troop strength numbered merely 5,000. But that 1st figure is more likely the casualties he suffered. Sapieha fled, understandably, from the field (the victorious cavalry charge was enormously effective), and the Swedish hold on Birze (modern Birzai) was never compromised (unless I am mistaken). Shame can lead a man to downplay his infamy (I would). Radoslow Sikora, the current Polish historian, provides Polish army records which state that it was possibly a higher number than Sapieha claimed - 2,000, but no higher. Well, it could very well have been higher, and Sapieha clearly didn't give an accurate count - a count smaller than the probable amount from the Polish view. There were no longer some 45,000 Poles/Lithuanians fighting the Ottomans to the south, and the truce agreed in late 1622 was in probably to gain time to prepare for assured upcoming hostilities; this comes from one from F. Nowak in his contribution to the Cambridge History of Poland to 1696, Pg. 480,

"...summer of 1622, a preliminary agreement was concluded in August. Renewed in November, the truce was prolonged year after year until 1625, though the sole object of each side was to gain time for war preparations."

Thus, unless one chooses to disbelieve professor Nowak, Krzysztof Radziwill and Sapieha would surely not have divided their forces (unless they were mobilizing them for the 1st time) after Gustavus' invasion with such miniscule numbers. After all, not more than 20 miles seperated them (one force is claimed to have been six miles away from Sapieha), and if we are to believe the scenario that Gustavus destroyed a force of merely 2,000 at most, what became of the other forces in the region, numbering another 3,000 (according to them)? There is no explanation that I can find. Why would Gustavus be compelled to force-march and ambush a force about two thirds of his size? He constantly tried to achieve truces. I believe his force was about 2,000 cavalry, including the terrific, light Finnish Hakkapeliitat and 1,000+ musketeers. From some accounts I have studied, the Poles and Lithuanians numbered about 2,600 cavalry and about 1,300 infantry. I have read some accounts claiming their infantry alone numbered more than 3,400, but this is perhaps an elaboration to sweeten Gustavus' victory. One account states that Jan Sapieha's army was deployed on a ridge with the expectation the Swedes would would emerge in march formation. But Gustavus appeared in battle formation, with the infantry in the center and cavalry on the flanks. The Poles were scattered from Gustavus' amalgam of cavalry charges supported by musket fire. The Poles/Lithuanians were indeed surprised by Gustavus' formation, and he exploited some disorder in their ranks, but I don't believe they were totally surprised in a non-fortified position, with only 1,500-2,000 men. To believe this would be to believe they were incredibly stupid, knowing an invader had recently come, even though it was the winter. The other commanders in the area were Radziwill and one Aleksander Gosiewski, who commanded smaller forces of perhaps 1,000+ each. I do believe the figure of 6-7,000 attributed to Jan Sapieha's force by some accounts is perhaps the number for all three combined, and they were divided, but close to each other; Sapieha's defeated army at Wallhof probably numbered no more than 4,000. Thus it was Gustavus who was outnumbered, and he achieved the decisive victory after a forced march of over 30 miles in 36 hours in difficult wintry conditions; the other Polish/Lithuanian forces, comparitively small, must have withdrew or surrendered. The Ottoman threat was now subordinate to Gustavus' presence, and to leave such a scant amount of troops in the wake of Gustavus' invasion was manifestly inviting disaster. Gustavus' army was swiftly becoming a disciplined, balanced force, in which morale was increasing. He took acute measures to properly plan for transport and supply; the fact Gustavus was better equipped to conduct a winter campaign than his enemy, in their own territory no less, illustrates his strategic and logistic sagacity. During the siege of Riga in 1621, he enthusiastically dug the trenches with his men. True, Gustavus established his position in Livonia and Polish Prussia by attacking while the Polish/Lithuanian forces were dealing with Ottomon (until 1621) and Tatar (Tartar) threats. Koniecpolski didn't arrive on the scene against Gustavus until November of 1626, due to his fighting with the Tartars, whom he crushed. Though Gustavus' entrenched positions in Polish Prussia wavered back and forth, his grip was never completely lost.

Furthermore, the Poles and Lithuanians knew Gustavus had just taken the towns of Mitawa (Mitau, modern Jelgava)) and Bauske (modern Bauska). They must have been in a 'time of war' frame of mind, regardless of the winter conditions. However, claims that Gustavus lost not one man is untenable. But it suggests that, if he was barely scathed, he did indeed surprise them.

When the way was clear for a new theater of operations for Gustavus in Polish Prussia, he resolved to secure control of the Vistula, as he had already secured the Dvina. The mouth of the Vistula poured into the Baltic at Danzig (modern Gdansk), and was the vital artery of Poland's economy. With the Vistual blocked, and Danzig captured or neutralized, the Polish magnates would certainly compel Sigismund III to make peace. This campaign would also relieve much stress, hopefully, on the Protestants in Germany, as Imperialists would come to the aid of Sigismund III. Gustavus landed near Pillau (modern Baltiysk) on the Vistula Lagoon (the Zalew Wislany, or Frisches Haff)) on June 25, 1626 with 12,709 men (1,209 cavalry), and 64 guns, disembarking from some 150 ships. He took Pillau after negotiations failed with his brother-in-law, Georg Wilhelm, the Elector of Brandenburg. This action threatening Poland's access to the Baltic. He discerned that he needed to occupy as much of the Baltic coast as he could before joining the struggle in Germany, and do it quickly; the Poles had been lax in concentrating forces to deal with him, and this he would take full advantage of. After the fall or surrender of Braniewo (Braunsberg), Elblag (Elbing), Frombork (Frauenburg), Orneta (Wormditt), Tolkmicko (Tolkemit), and Malbork (Marienburg) by early July, 1626, he was in possession of the fertile and defensible delta of the Vistula in Prussia, which he viewed as a permanent conquest. Axel Oxenstierna was commissioned as the region's first governor-general. Communications between Danzig (modern Gdansk), which was his hope for a valuable base and depot, and the Polish interior were cut off by the erection of the first of Gustavus' famous entrenched camps around Tczew (Dirschau). Putzig (modern Puck), NW of Danzig was captured, and by storming Gniew (Mewe) on July 12, 1626, the Poles were further threatened with losing access to Danzig from the interior. Again, the terrific Koniecpolski was at this time fighting the Tartars in the Ukraine, and Zygmunt (Sigismund) III was slow (such criticism is in hindsight, of course) to mobilize against Gustavus' landing on June 25, 1626 at Pilawa (Pillau, modern Baltiysk).

Gustavus never attempted a major storm or siege of Danzig, but remained content to try to blockade the great port, which clearly was viable, being he cut its communications from both sides. But he could never completely prevent it being provisioned by the sea, and the city's ability to hold out practically neutralized Gustavus' successes throughout the four year campaign. Due to the impracticability that the city could be reduced to straits, he sought to secure its neutrality. This is where he might have been a little rash and lost patience; he was already eyeing the situation in Germany nad might have been hoping to bring the Polish war to a speedy end, which depended on the submission or neutrality of Danzig. A less hectoring style of diplomacy might have procured Danzig's neutrality. It is indeed mentioned in one of my sources that he reconnoitred the fortress of Wisloujscie (Weichselmunde), and he began recruiting from his newly acquired territories, including the procurement of valuable, indigenous horses.

In late August of 1626, 2,650 Finns arrived to reinforce Gustavus, of which 650 were cavalry.

At the battle of Gniew (Mewe), fought in September, 1626, Gustavus and his officers, most notably Heinrich Matthias von Thurn and John Hepburn, won an impressive but not overwhelming victory. The wooded terrain around Gniew was utilized by Gustavus to neutralize any devastating effect the Polish cavalry could usually rely upon. It was in late September, 1626 when Sigismund III finally arrived upon the theater of operations, now commanding a field army in the vicinity of Grudziadz (Graudenz). After conscriptions were carried out from Grudziadz and Torun (Thorn), his force in the field totalled 11,940 men; over 10,000 were cavalry - 3,980 husaria, 5,050 kozacy, and about 800 reiters, and some dragoons. The infantry force numbered perhaps over 5,000 Polish, German, and Hungarian footmen (doubtless many of whom were haiduks). Torun lies on the Vistula a little over thirty miles south of Grudziadz. Sigismund III wanted to blockade Gniew, with the intention of drawing Gustavus further south, away from his base at Tczew and the vicinity around the Danzig perimeter. The Poles had recently retaken the fortress of Orneta (Wormditt), perhaps proving other fortresses Gustavus had easily taken earlier could not serve as a permanent defenses. Thus he had to march out against Sigismund III. Led by Sigismund III and his son Wladyslaw, the Poles advanced towards Malbork; on meeting the Swedes, whom they outnumbered, some skirmishes broke out, and the Poles withdrew south, crossed the Vistula at Nowe (Neuenburg), and began to siege Gniew from the town's south side. Though Sigismund III established himself on high ground to the west. Though a strong position, Gustavus set himself up at no disadvantage: he assembled a picked force of 3,500 men (500 horse), drawn from the vicinity of Tczew (Dirschau). His troop strength in the fiel in the vicinity of Tczew numbered 7,661, of which nearly 1,274 were cavalry. He headed for threatened Gniew, and to challenge Sigismund III's position, he both disposed his men in wooded terrain along the Vistula and behind an anti-flood embankment, good for a reconnoitring position, as well as a good and defense against enemy cavalry. The relief of Gniew was a necessity for carrying out the campaign he intended, so he devised a tactic to effectuate its relief. With some light horse and artillery, the Poles had occupied a position athwart his path. Gustavus resorted to a ruse, making his movements appear as a reconnaisance, and proceeded to withdraw. After this clever disposition apparently deceiving the Poles, he then ordered Thurn and John Hepburn to create another diversion and cut a passage over a strongly fortified hill defended by the Poles, who vastly outnumbered them. Thurn and his cavalry diverted the Poles' attention by demonstrative actions, and held up in some serious skirmishing with the lighter kozacy. The Poles were given the impression the Swedish garrison was going to be drawn from within Gniew, and that the place would fall to them in any event, so they made no immediate advance, but failed in a cavalry charge against Gustavus' carefully prepared infantry positions, whose firepower was too strong; though loss of Polish life was apparently minimal, the Swedes were trained to fire more at horses, thus many more were dismounted. Perhaps they should have attacked sharply in significant numbers and closely observe the region to ascertain Gustavus' real intentions. If they had, perhaps the campaign for Gustavus might have ended here for good. But that's 20/20 hindsight.

Simultaneous with Thurn's diversionary activity, the infantry column commanded by Hepburn, which had started at dusk and unseen by Sigismund III's men, approached the enemy position by working around it and ascending the hill by a narrow and winding path, which was encumbered by difficult terrain. Weighed down with muskets, cartridges, breastplates, helmets, and defense obstacles (I'll explain in a bit), they made their way up through the enemy's outposts unobserved, and reached the summit, where the ground was smooth and level. By tactical surprise, here they fell at once upon the Poles, who were busy arranging their trenches. For a time, Hepburn and his men gained a footing here; but a deadly fire, mostly musketry, opened upon them from all points, compelling them the to fall back from the trenches. But they now found themselves charged upon by armored husaria under Tomas Zamoyski, thus they certainly would have been soon repulsed. Hepburn drew off his men till they reached a rock on the plateau, and here they made their stand, the musketeers occupying the rock, the pikemen forming in a wall around it.

Gustavus had provided them with valuable defense items, which were utilized effectively here on this emminenece held by the Poles - a portable Cheval de Frise (French for 'Frisian horses'), and the Scweinfedder (the 'Swedish feather', or 'Swine feather'). The bayonet was not yet in use, and musketeers often adopted defensive weapons to protect themselves from cavalry. This small version of the Cheval de Frise consisted of a portable frame, probably a simple log, with many long iron spikes protruding from it. It was erected more in camp and principally intended to stop cavalry dead in its tracks, but was not a serious obstacle to the passage of mobile infantry. But here Hepburn was using smaller versions. The Scweinfedder was a pointed stake (a half-pike about seven feet long) and musket-rest combination, which had replaced the more cumbersome fork-firing rest. The stake was planted pointing toward the enemy cavalry (the musket rested upon a loop) to act as a defensive obstacle, particularly against shock cavalry. Gustavus' Swedish army used the Scweinfedder in the Polish campaign more so than against their enemies in Germany later probably because the terrain offered better cover against cavalry, and there was less cavalry in Germany than Poland. They quickly placed these obstacles along their front (remember, they were portable), and it aided the pikemen greatly in resisting the desperate charges of the Polish horsemen. Their German allies, armed with muskets, aided immeasurably in the effectuated defensive. Hepburn and his force withstood the Polish army for two days. Soon, however, as I stated, they would certainly be overcome by an amalgam of fire and shock from a preponderance of enemy forces (the time between reloading rendered them extremely vulnerable), so they withdrew, both sides being proportionately scathed very little.

While this desperate action was taking place, and the attention of the Poles entirely occupied on Hepburn, Gustavus himself managed to pass a strong force of men and a store of ammunition into the town from the north side, and then turned to protect Thurn's withdrawal, at which point the husaria could make no headway before Gustavus' triple-lined infantry firepower - the Swedish Salvee; two husaria charges were unsuccessful. Sigismund III, seeing that Gustavus had achieved his purpose of relieving Gniew, retired with the loss of some 500 men. It is quite possible that Sigismund III could have thought Gustavus was in force the entire time, and with his artillery, thus they may have thought he was trying to draw them from their good position. The Swedes did not outright beat the Poles and compel them to flee scatteringly, but the town of Gniew was re-victualed and the garrison substantially strengthened by Gustavus. Moreover, the terrain around Gniew would surely be utilized by Gustavus to neutralize any devastating effect the Polish cavalry could usually rely upon. Nevertheless, it was a superbly handled operation on the part of Gustavus. The Polish historian Jerzy Teodorczyk calls this battle the first defeat of the husaria, but I think it should more appropriately be called the first prevention of a defeat at the hands of the husaria. More reinforcements arrived in mid-September for Gustavus.

Though Gustavus would begin to endure some severe harassing from better-led enemy forces, with the terrific Stanislaw Koniecpolski coming onto the scene in November of 1626, the object of his campaign so far a success (albeit he was barely challenged militarily, and he wasn't gaining what he wanted with his prime object, Danzig) - to secure a base of operations encircling Danzig; the Swedes' main holdings were Putzig (modern Puck), Tczew (Dirschau), Gniew (Mewe), Elbing (modern Elblag), Brunsberga (Braunsberg, modern Braniewo), and Pillau (modern Baltiysk). Oxenstierna was placed in overall command in October, as Gustavus returned to Sweden to organize reinforcements. It seems Sigismund III overtured peace, but the ministry and people of Sweden supported Gustavus' refusal to what he deemed were unacceptable conditions, which included the kingship be returned to Sigismund III.

At the end of 1626, probably in November, Koniecpolski, who had arrived with great celerity from the east with a little over 6,000 men, began a counter-offensive to reopen the Vistula and relieve the blockade of Danzig. Now, the Swedes would be up against a superb commander, commanding the vaunted husaria. Cavalry action took place around Neuteich (modern Nowy Staw) on January 7-17 of 1627, resulting in Swedish reiters heavily scattering Polish foragers. But Koniecpolski swiflty retook Putzig and captured Gniew by stout diversionary moves, and entrenched his forces. He had quickly captured Putzig in early April, 1627, which reopened Danzig's communications with Germany. But the Swedes' lines to Pillau remained intact. Moreover, the Swedes defeated a Lithuanian force near Koknese (Kokenhausen) in December, 1626, detracting a threat to their position there. On April 13, 1627, Stanislaw Koniecpolski decisively intercepted a force of about 2,500-4,000 recruited from Germany, marching east from Hammerstein (modern Czarne) through Pomerania for Gustavus, and drove them back to Hammerstein, which he forced two days later into capitulation. Earlier sources state this force numbering 8,000, but this is certainly a magnification. I have recently read it was 4,000, and some say the figure of 2,500 was the total number, others say 2,500 was the casualty figure. Radoslaw Sikora says Koniecpolski's force outnumbered the force coming from Germany by very little, thus, if we sustain Sikora's information, 8,000 is certainly incorrect. Whatever the actual number, few Swedes, if any, took place in the battle, and the captured infantry were incorporated into the Polish army. Much of the surviving cavalry rode back to Germany. As it turned out, the Swedes' plans to strike at Koniecpolski from the other direction was foiled by the flooding of the Vistula.

Gustavus returned to Poland, landing at Pilawa (Pillau, modern Baltiysk) on May 8, 1627 with about 7,000 infantry, followed a month later by 1,700 cavalry. When he reached the army entrenched around Tczew (Dirschau), he found his total troop strength in Poland had increased to roughly 22,000 men, due to much recruitment; 11,150 foot and 1,400 cavalry were in the field, and 8,540 were stationed in garrisons (1,090 cavalry, of which 200 were dragoons), and Koniecpolski could move freely. Georg Wilhelm, the Elector of Brandenburg, now took up arms against Gustavus, but Gustavus made short diplomatic work of the small force of about 2,000 men, positioned near Mohrungen (modern Morag). He enlisted them under his own standard. Wilhelm would thereafter remain neutral. After some cavalry skirmishing in early May, in which Gustavus was nearly cut down, he began to reconnoitre the redoubts around the western mouth of the Vistula, a strip of land held by the citizens of Danzig. Viewing the works from a boat, he was shot in the hip on the 25 of May, 1627. This laid him up, delaying operatons, and the Poles began to concentrate their forces. Sigismund III threatened Jakob De la Gardie's position in Livonia, and Gustaf Horn was sent with men to ready themselves for any contingencies. The Swedish operational goal now was seemingly to buttress the region of the eastern side of the Vistula they held, and to defend their hold on Tczew (Dirschau). Danzig (modern Gdansk) now could only be threatened from the east, as Putzig was in Polish hands. Koniecpolski didn't possess enough infantry and artillery to threaten Tczew (Dirschau) itself, so his operational aim was to deny the Swedes access to the eastern routes to Danzig, and lure Gustavus into the open field quick enough to do battle before Swedish artillery could be effected, a situation which would certainly favor his husaria. However, Koniecpolski did seize Gniew (Mewe) in July of 1627, with it procuring a vital crossing-point on the Vistula. He then began reconnoitring the Swedish works around Tczew (Dirschau) in early August with about 7,700 men, of which nearly 4,500 were cavalry. Gustavus' army was slightly over 10,000, of which over 4,000 were cavalry. He possessed maybe twenty guns at most. The Swedes crossed over the Vistula River and garrisoned Tczew (Dirschau) with about 1,600 men. Knowing that the Polish cavalry was virtually impossible to beat on open ground, the Swedes expanded their bridgehead with a longline of fortifications. The route west of Tczew (Dirschau) ran through the defile of the marshy Motlawa river. The Polish moved to block the Swedes from advancing beyond this point, encamping on the western side of the river, but Gustavus knew that the Poles didn't have enough infantry to storm his fortifications, thus he didn't need to 'breakout'. But he also was keenly aware that his cavalry was vulnerable. He had to be careful. He had some success against the Poles by using fortifications, artillery, and defiles to prevent the Poles from using their cavalry to its full potential, but he had to be cautious. Koniecpolski was a very experienced soldier and despite his limited resources he had put the Swedes on guard. His army was faster on the march and had shown remarkable ability to outmaneuver the Swedes in the open. The Poles fortified their encampment, so it was a standoff with both armies fortified on either side of the river. Both generals knew that an all-out attack by either side would be a disaster; the answer was to probe and hopefully draw the other side out, of force them to withdraw. The Battle of Tczew (Dirschau) was set to be fought, beginning on August 7, 1627.

The Poles deployed pickets as Dutch negotiators were in Koniecpolski's camp. These negotiations were not bilateral, as the Dutch were mostly in disfavor of Gustavus' campaigning in Poland because it disturbed their trade with Danzig, and Albrecht von Wallenstein's, successfull in Germany at this time, promised Sigismund III assistance. The Poles left themselved vulnerable, a situation any good commander will exploit - to strike at one's Achilles Heel, particularly when the enemy will destroy you with their vaunted weapon if fought under conditions viable for the utilization of that weapon. In this case with the husaria, an open field. Gustavus' concern of the hussars was genuine, and that fear fear of them understandably influenced his operational strategy. As devastating and impressive the Battle of Kircholm in 1605 was a display of the husaria formidability and prowess in the open field when drawing an impetuous opponent (Karl (Charles) IX) into their favorable conditions and off their high ground (Karl thought they were retreating), it induced a false sense of security. When Gustavus invaded in 1621, many fortresses throughout Livonia and Ducal Prussia on the Baltic were not defended adequately. Gustavus took advantage of this situation very smartly, and coupled with his army revisions, he would never again allow, to reiterate, a defeat like Kircholm to afflict his army.

Gustavus attacked the Polish picket lines, and retired into his entrenchments when Koniecpolski counter-attacked in force with much of his cavalry. Gusatvus refused to be lured out, and Koniecpolski refused to be lured in, as Sigismund III had at Gniew the previous year. But Gustavus did attack the husaria here at Tczew - simply not when Koniecpolski wanted, or expected, him to; the remaining six Choragiews withdrew west along the marshy causeway, and Gustavus fell upon them swiftly with his cavalry, catching them off-guard. Here at this point of Battle of Tczew (Dirschau), Gustavus' unit of cavalry under Henry Matthias Thurn attacked six Choragiews (Banners) of Polish cavalrmen, after Koniecpolski left with the bulk of his horsemen when it reached a point Gustavus seemingly wouldn't come out to fight. But the stout Polish counter-attack, which included the arrival and attack of a unit under Marcin Kazanowski, would have most likely beaten them, as Thurn's right wing was seriously threatened. But such a contingency Gustavus was prepared for, as he held a reserve unit under Erik Soop on hand, and came in and, combined with Thurn's stabilizing of his own unit, sent the husaria (and two Choragiew of lighter cavalry) into flight. The husaria were the most formidable heavy cavalry (though 'heavy', they could move darn fast!) of their day, but Gustavus' reformed cavalry was hardly three times worse than the husaria; if the Poles had been outnumbered by such vast odds (three to one), as they claim, they would have been crushed. As it happened, they were thrown back, but not scattered terribly. By whatever they were outnumbered upon Gustavus' surprise salvo, the arrival of Kazanowski closed that gap, and they still were repulsed. A Choragiew numbers about 200 men, but the numbers vary. Thus, I think it is possible 1,800 Swedes defeated 1,200 Poles that first day around Tczew (Dirschau). The Poles' counter-attack would have seemingly handled the first wave, but Gustavus was prepared. Also, I have read from one account that the Poles retreated because all their lances broke. With respect to who wrote that, this is not credible. All their lances (kopias)? Every one of them? If this was true, could they not fight the Swedes with their sabres (szablas)? True, a hussar's kopia was constructed with its center bored out to lighten it, and its length, over 15 ft. (5+ meters), made it pliable to the point it would often break. Moreover, it was considered a dishonor for a hussar to return from combat with an intact kopia. But a broken kopia can still be 10 ft., certainly still useful, and a hussar carried more than one into battle. I realize this is all rationalization, though.

Gustavus was merely exercising more patience then they were. Sure he wanted to leave his camp, but, again, not under their expectations or terms. For all he knew (again), they were trying to draw him out, feign a calculated retreat, and attack him in the manner that befell his father 22 years earlier. The Poles claimed six banners were 600 men in this battle. From what I have read, a banner, or Choragiew, contains around 200 horsemen (sometimes 240). This is from Radoslaw Sikora, amid his article on the Hussars' tactics,

"...A banner with 200 Hussars attacks a regiment of infantry with 600 men (400 musket and 200 pike)...",

This is comes from one Marciej Rymarz's description of the Polish/Lithuanian attack on Swedish-held Warsaw in 1656,

"...The Hussars totaled approximately 1,000-1,100 men, in eight banners (six Crown and two Lithuanian), so were quite few in number especially compared to the force that might have been raised in earlier years..."

Well, I'm guilty of over-rationalization, as I should consider there was no fixed number for a Choragiew; it seems they could be as low as 60.

We are indeed talking about the 'earlier years', specifically here at Tczew (Dirschau), thus it is more likely the 1,800 horsemen under Henry Matthias Thurn and Erik Soop faced 1,200 or so husaria (maybe more, with Kazanowski coming onto the scene, if he wasn't counted in the enumerations), who were left behind after Koniecpolski thought they weren't coming out of their camp. Maybe some Choragiews numbered 100 or less at other times, but in this case, 600 husaria against three times their number of Swedish cavalry, now only slightly less formidable per se, would have been crushed at a much quicker level than what happened. Koniecpolski's quickly administered counter-attack indeed would have seemingly overwhelmed Thurn, but Soop was placed to stabilize such a contingency, which he did. This 1.5:1 (or a little less) ratio was enough for Gustavus' reformed cavalry,and supporting musketeers, to repulse them. They pursued them until the Irishman Jakob Butler's (or Walter Butler's?) musketeers, well placed, prevented any overwhelming rout of the withdrawing husaria. What a novelty for the Swedes to witness: the husaria withdrawing after a fight with their own horsemen, even if not a scattered and wildly broken retreat. In another clash of horsemen, Herman Wrangel, positioned with conduciveness, held up against the counter-attack by Kazanowski. But this also halted any Swedish futher advance. If not thoroughly beaten back, the fact Kazanowski withdrew and Wrangel did not clearly indicates the Poles conceded. Both sides may have been in the same position when they started, but the first day was a tactical success for the Swedes; it was the Poles who withdrew and returned to their camp, not a mutual scenario. Radoslaw Sikora's implication that because the Poles weren't destroyed means they didn't lose that first day (he thinks the battle was a draw) is not tenable, in my opinion. Why must one destroy the enemy to qualify as a defeat of that enemy? How many victories akin to Cannae and Mohi have occured throughout military history?

With all that opined, though, one thing is certain: the Polish husaria were too strong for Gustavus on their terms. He could only beat them with a method of supporting firepower for his cavalry, and entrenchments with his infantry, as well as careful maneuvering, including catching them unawares with his cavalry. The claim that Gustavus' reformed cavalry could match the Poles on equal terms is, in my opinion, quite superficial. But his mounted arm was improving by the year.

The Battle of Tczew (Dirschau) commenced on a second day, and despite the descriptions I have read that the Polish guns were in a better position, and this position well protected, they never did inflict upon the Swedes with any significant battering, and Gustavus' leather guns and other cannons could have probably, with a little time, circumvented any defilades around the Polish camp (assuming the guns would not have high proportional problems of premature igniting, as was often the case). But a serious wound to Gustavus occured, in which a bullet hit his shoulder and then lodged into his throat, and another suffered by Johan Baner, who was in command of the important bombardment, precluded a thorough Swedish victory. Following his serious injury, Gustavus placed Herman Wrangel in overall command, and for some reason Wrangel, reputed to have been a more cautious commander than Johan Baner, halted the Swedish attack and ordered the Swedish troops to hold their postions in the Motlawa Valley. Once darkness approached, the Swedish army returned to it's fortifications at Tczew (Dirschau). But why did the attack stop, as victory seemed imminent? It has been theorized that Gustavus believed his wound was mortal; he had been shot in the shoulder with a 14-15 mm ball, which permanently dislodged into his neck, causing pain for the rest of his life. He perhaps didn't want to risk the loss of his army on this day of his death.

Theodore Dodge's description of the Battle of Tczew (Dirschau to Dodge, as he used German-language sources) is brief. He tells us the Polish cavalry was beaten back through the village of Rokitken (modern Rokitki). The Swedes cleared Polish pickets, much like the day before with their Finnish allies. They also seemingly cleared Rokitken of enemy troops, or, as other accounts say, perhaps the village of Lunau (Lunowo). Whichever village, a little to the west of Tczew (Dirschau), it was set ablaze. The smoke from the village provided a useful screen for Gustavus to advance his guns. The husaria were reluctant to move. Some Swedish apologists may say because they were worried about Gustavus' potential with tactics of firepower; Polish sources may state they hesitated due to the loss of all their kopias (lances). The consensus holds that there was concern among them that their German infantry allies were on the verge of defecting. If so, one can assume that they were in an inauspicious situation in this battle against Gustavus. The Swedes moved their guns forward to bombard the Polish camp while the infantry of both sides skirmished along the river. The Polish camp was in defilade from the Swedish guns, so the initial Swedish bombardment had little effect. But that wouldn't have lasted with the maneuverability of Gustavus' artillery units, and combined with the distrust of the German troops, the Polish troops came very close to mass panic. Koniecpolski held cohesion intact, and it was the Swedes who actually withdrew, following the injuries to their top two commanders.

This is from Franklin D. Scott's Sweden: the Nation's History, Pg. 172,

"...Gustav Adolf's leather-wrapped guns worked effectively, and the Battle of Dirschau (Tczew) showed the Swedes had finally learned the lesson of their humiliating defeat at Kircholm in 1605; now their cavalry bested the Polish - reputedly the best in Europe. However, the outcome of the 1627 season still failed to convince the Poles they were beaten; and they took heart from the prospect of imperial support..."

I think the Swedes had indeed learned their lesson from Kircholm, but it didn't reach a point where the leather guns worked effectively to win the battle completely, due mostly to the injuries to Gustavus and Baner. It was not a complete victory.

From Michael Robert's Gustavus Adolphus, Pg. 55,

"...Polish resisitence in 1627 began to organize itself, and proved tougher than had been expected. The run of fighting was indeed in Sweden's favour: a victory at Mewe in 1626 and one at Dirschau in 1627 (Gustavus was seriously wounded in the second of them); but nothing like a Polish collapse, either military or economic..."

This is from Brent Hull, who put together the wargames for Gustavus' battles, apparently consulting Radoslaw Sikora (my source is Sikora, not a 'board game'),

"...In a tactical sense the Swedes had been victorious on the first day of the battle, and had it not been the King being seriously wounded the second day may have ended differently. The choice of ground, fortifications, and implemented combined arms had allowed the Swedes to successfully fight the vaunted Polish cavalry. Pulling these factors together required great caution and made decisive action unlikely. In a larger sense the outcome was a major strategic success for the Poles. Koniecpolski had prevented a Swedish breakout, thus securing the overland routes to Gdansk. Within weeks the construction of the eastern fortifications of Gdansk were completed and the window of vulnerability closed."

I somewhat disagree with what is assessed concerning 'the larger sense', but Hull (or Sikora) perhaps has a point worth considering, in terms of the immediate result. Koniecpolski did not prevent a Swedish breakout (Gustavus wasn't trying to conquer further into the interior), in the sense the Swedes were trapped within their works, thus trying to escape, and if the overland routes to Danzig were secured by the Poles, this situation hardly lasted. Gustavus convalesced for a few months, and the blockading of Danzig (Gdansk) continued by his fleet under Nils Stiernskold. When Gustavus was healthy enough to return to field duty, Putzig (Puck) was recaptured (unless my source is wrong), cutting communications with Germany again. His fleet did suffer defeat on November 28 off Oliwa from the Polish under Arend Dickman and the Scotsman James Murray. The Poles had ten ships total against the Swedes' six, but only four galleons against the Swedes' five. Dickman and Stiernskold both perished. Though a compliment to the prowess of these privateers organized by Sigismund III, it was an empty naval victory, in a strategic sense; a stronger Swedish fleet was brought up, and Gustavus drew his lines closer to the city. He achieved this by expanding his base of operations towards the south-east by recapturing Orneta (Wormditt), and Guttstadt (modern Dobre Miasto) was captured by Ake (Achatius) Tott before the winter set in. The former was stormed, the latter surrendered. From my view, the main thing Koniecpolski accomplished from the battle fought around Tczew (Dirschau) was to prevent the destruction of his smaller army by superb maneuvering and handling of his troops, when morale dropped. By December, 1627, Gustavus was back in Stockholm, mainly for the benefit of his health. I think his grand strategy against the Polish-Lithuanian was about controlling the Baltic, particularly blocking the Vistula, not significantly breaking out of his quadrilateral in Ducal Prussia, as claimed by some. He did control area as far south as Brodnica (Strasburg).

Danzig's trade reached a point of becoming paralyzed, and the Polish nobility was suffering financially by having to store crops of corn one after the other while waiting to export it. Though Gustavus became more and more filled with anxiety by the actions of the Imperialists under Wallenstein in Germany, his commanders in Livonia were holding up against the enemy. This enabled Gustavus to feel confident to resume the offensive into Polish Prussia in the summer of 1628. But Sigismund III felt brighter hopes were on the horizon with the developments to the west favoring the Catholics. The Protestant were supplicating to Gustavus, and he could afford just 1,100 men, in two detachments, and some munitions for the defense of Stralsund. Gustavus didn't want to risk an attack upon Koniecpolski unless favorable to do so, with Koniecpolski thinking likewise, and the war became one of maneuver, with neither side willing to face each other without advantages of terrain or fortifications. More often than not outnumbered, the Poles began pillaging their own land to impede the Swedish source of supply. On July 15, upon moving towards Danzig, Gustavus sank a few ships of Danzig's fleet with his leather guns, including the flagship. Danzig could possibly have been reduced by hunger, but again the floods came, which forced the Swedes out of their positions along the Vistula. Gustavus was thus compelled to lift the land blockade of Danzig completely.

In the late summer of 1628, around the vicinity of Grudziadz (Graudenz), the armies of Gustavus and Stanislaw Koniecpolski, according to Polish sources, were opposite on another a few times, but with no battles taking place. Koniecpolski's dispatches to his government stated his attempts to provoke Gustavus to come out and fight, with the Swedish king refusing to come out of his earthworks. What Koniecpolski, or the Polish chroniclers didn't mention, or didn't realize, was that the excellence in the Swedish army was largely influenced by the presence of Gustavus himself, their personal commander as well as their king, at least for the Swedes themselves; he led by personal example, with no task too small or menial, even grabbing a spade himself to lessen the feeling of indignation amongst some of his mercenaries about the digging of trenches. Gustavus greatly realized the importance of field fortifications, and soon employed sappers to dig troops entrenchments and cannon positions. Thus he gave battle only when he believed appropriate. Attacking ready husaria in the open was not appropriate, as the only way for an enemy to avoid destruction by the husaria was to keep to terrain in which cavalry formations could not operate fully, evidenced at Gniew (Mewe). But Koniecpolski prudently stayed at a distance out of range of Gustavus' artillery. But the Swedes operated in the open too, though not without risk and loss, and were neither able to force a decision under their terms, and the Polish campaign of harassment throughout 1628, influenced in part by the lack of support form the Sejm for Koniecpolski, cost Gustavus some 5,000 men (some deserted). Of note is that the Swedes and their allies suffered more from pestilence throughout this war than by enemy weaponry. In October of 1628, Gustavus did successfully storm Osterode (modern Ostroda) with a force of 4,000 men, equally divided between musketeers and cavalry.

By this time Gustavus was clearly eyeing the conflict in Germany, as Denmark became his ally, albeit not completely without reservations, and he aided in the successful defense of Stralsund, though much credit goes to the Danes, who saved the port in early July, 1628. This success would soon open for Gustavus an important foothold in Germany, as well as protect his position in the Baltic. The 1,100 men sent by Gustavus to Stralsund under Leslie, of which about 500 first arrived in late June, along with the Danish fleet's destruction of several vessels sent by Sigismund to aid Wallenstein, were instrumental in the defence of the important stronghold; Tilly and Wallenstein, two noteworthy leaders who had run ragged over the Protestants since 1626, appeared to be bringing a certain overall Catholic victory. But the imperial reverse at Stralsund should not militate against Wallenstein's skill; had Gustavus not failed before Danzig?

Theodore Dodge drew on Swedish sources, most notably a German translation of the Svenska folkets historia by Erik Gustav Geijer, and letters from Gustavus himself, which Dodge said were very modestly put. Dodge emphasis the Swedish accounts have many gaps, due mostly to a terrible fire in Stockholm in 1697, which destroyed a huge amount of important documents. He also wrote in a time (1890s) which since has seen superior texts. But he tells us of a battle occuring in 1628 before the serious flooding of Vistula, which compelled Gustavus to lift the blockade (from inland) of Danzig: