East of Cairo, 1125.

The onrushing years had not been kind to Vissarionas ek Lesvou. The scar across the top of his head had thickened with age, causing him constant discomfort and spreading hair loss down the sides of his scalp. His closest friend and servant Rafi had grown into a man in his own right, but there was a wedge of distance between the two of them that the passage of time was worsening. Vissa often wondered now if Rafi would remain by his side after the Crusade.

Ahh, and there was the matter of that Crusade. Back in Constantinople, with fire and fury in his guts, Vissa had imagined a single clean stroke to wipe away the sins of the infidel, protect the holy places of Orthodoxy, and, in his heart of hearts, reclaim Aliya's favor for himself.

It had not been so simple. First he had spent a fortune from the funds secured in Cairo to hire Genoese craftsmen and sailors to crew his vessel. They had claimed to be in Constantinople waiting for the German crusade to pass so they could hire on. In fact, as Vissa discovered only after weeks aboard the ship, they were rebels against the Milanese who currently governed Genoa and had been existing as little more than pirates. They swore their changes to his ship would help it outpace his comrades in arms, but how was carving a lewd statue of a half fish woman on the prow supposed to help? Vissa had grown up in a little island fishing village and so had no fear of the water, but neither was he a sailor with any knowledge of the open sea. Once they lost sight of the coast the lives of the Crusaders were completely in the hands of these Genoese 'rebels' and their odd notions of safe sailing.

For one thing they insisted that the soldiers drink an astonishingly vile tea, vowing that it would keep them hale during the long voyage. Vissa had refused, though even Rafi eventually developed a taste for the stuff. Halfway through the trip Vissa had then developed an affliction of sores and weakened teeth. Three of his had fallen out. The rest of the men remained healthy, but Vissa could not shake his illness and spent long days alone in his cabin. The sailors called it scurvy, but privately Vissa thought it might be a curse from God for the increasingly crude dreams he had of his time with Aliya.

Then Vissa had discovered that among the sailors it was common to... lie... with one another after a certain amount of time at sea. The men swore up and down that it was lucky, that it was necessary, that it prevented trouble on the ship, but Vissa, sick of the sea, sick of the scurvy, and sick of the disgusting habits of the men of Genoa absolutely forbade it. Five sailors had to be hung at sea, and eight more took lashes, some more than once, before the practice came to an end.

Then there was the whale, or perhaps The Whale. The less said of it the better.

At last, at long, long last, Vissa and his men had reached the coast. Not first, not fastest, but perhaps the better for it. The death of Kosmas Mavrozomis gave caution to all the remaining crusaders, though it was a steep price for the warning. During the march south he had joined forces with his Order mates, Stavros ek Amarinthou and Varthomlomaios Ksiros. At last they were within sight of the walls of Cairo. At last the end was nigh!

Aliya's perfume seemed to drift in the very wind. Vissa walked about in a state of heighted excitement. The other men took it for religious fervor, or for the end of his scurvy affliction, but in truth his every waking thought was driven by the desire to again hear her voice, again feel her skin against his own. He gave no sign of it, none, and so men mistook the reddening of his cheeks for a passion for God, and called him 'little father' and Priest Vissa, half seriously.

The Egyptians in the area had all stood aside from the Crusaders, not challenging their ride across the countryside to the bridge. Vissa had wondered at this, seeing that Cairo was their capital and nearly in reach. Once they had finally encamped at the bridge, however, their plans became clear. Forces on both sides of the river abruptly moved to make an assault on the Crusader's camp on the eastern bank of the river.

Stavros, the most experienced commander and by mutual agreement in overall control of the army, had a good cover of scouts out on both sides of the river. His men reported that the force on the western bank was comprised of only a few companies of light infantry and archers, while the army advancing on the west bank was far larger and led by a Saracen noble. Stavros' snap decision was to abandon the camp and force the bridge against the weak blocking force immediately. With a bright sun lighting the morning sky to the east Stavros and his company of Lancers thundered onto the bridge, fully expecting the enemy to lash out with a storm of arrows.

The Egyptians, however, obviously had strict orders to hold the bridge at all costs. All four companies of men rushed onto the bridge and engaged Stavros' heavily armored men at close quarters. The slaugher rapidly became immense as horses shoved screaming Fatamids into the river and General Amarinthou's guardsmen butchered the lightly armored infantry.

Vissa and Varthomlomaios had, meanwhile, ridden away up the east bank of the river to delay the arrival of the second Saracen army. With a vengeful roar the two men led a galloping charge into the advance guard of light infantry and Turkomen, scattering and killing dozens before pulling back with the enemy general and his cavalry in close pursuit.

At the bridge the first company of Egyptian archers broke, throwing down their weapons and attempting to surrender. When their captain turned away from the battle for a moment to attempt to rally them Stavros personally leaned far out of his saddle to nearly behead the man, shattering the will of the remainder to fight.

All that remained was to chase down the fleeing remnant and hold them at the point of a sword.

Behind Stavros the remainder of the army crossed the bridge, the Great Cross company trailing behind, and set themselves to receive the assault of the second Saracen army. The spearmen pushing the cross left it at the mouth of the bridge as a symbol of defiance in the face of the infidel. Stavros knew well that if the worst should occur, if the army should be pushed back from the bridge, the men would fight to the death to reclaim that cross. Soon Varthomlomaios rejoined the main body of the army, the Saracen attackers having slowed behind him to await their infantry. Of Vissa there was no sight, the two groups of guardsmen having split at the far end of the bridge.

North of the bridge, alone on the east side, Vissarionas and his guards rested atop a small hill and watched the Fatamid general ready his assault. A small, near broken company of Turkomen were harassing Vissa's men with light arrows, but otherwise he stood unopposed. Gathering his Bedouin light cavalry the enemy commander decided to try to force the crossing himself, perhaps because he could see that Stavros' banner was far to the rear of the army capturing the last of the blocking force.

It was a horrific error. The timbers of the bridge were drenched in the blood of Saracen light infantry, making footing uncertain for the horses and giving Stavros' archers ample time to thin the numbers of the light cavalry now crossing. The Great Cross prevented a true charge from forming, though the horses made their way around it easily enough, and so the enemy staggered slowly into battle against well prepared spearmen and religious fanatics. Worst of all for them Varthomolaios had momentarily struck his banner to bait them, and he now raised it once more and charged into the battle. The Bedouin, accustomed more to raids than heavy fighting, lost their will to continue the struggle almost immediately.

With only his own scattered guardsmen Surahbil al-Fihri must have known he could not force the bridgehead. He looked about in horror at his fleeing allies, and raised his horn to blow, perhaps trying to summon his infantry to aid him.

Then, steeling himself for the embrace of death, he commanded his men to fight to the last.

Across the river the Saracen heavy infantry were preparing to charge to aid their master when a pair of fleeing Turkomen rode by screaming a warning which whipped away, unheard, in the wind. Moments later, while the Fatamids hesitated and their Lord died, Vissarionas ek Lesvou and his guardsmen broke over the hill and swept down on the enemy's light infantry with a crushing charge.

A roaring cheer announced the fall of the banner of Surabhil on the far bank, and Vissa's guardsmen, their work of pinning down the enemy infantry now done, fell back still under the plinking fire of the few remaining Turkomen. As Vissa and his guardsmen worked their way around to pin the horse archers against the bridge the Saracen's remaining captains paused for a moment to consider their position. If they attempted to flee those heavy horsemen were cruising around behind them like sharks, waiting to pick them off, and their Sultan in Cairo would not look favorably on the failure to relive them. On the other hand they still outnumbered the Byzantine infantry on the far bank, and it was even vaguely possible that they might yet rescue their commander and carry the day. Just as Vissa engaged the remaining half company of Turkomen the Fatamid heavy infantry bellowed out a command to their lighter fellows to charge, and several hundred of the enemy began to cross the bridge under a light hail of harassing fire.

Vissarionas saw their renewed determination, and immediately saw what must be done to break it. Commanding his men to ignore and ride through the Turkomen, breaking their ranks and their will to fight along the way, Vissa charged onto the bridge behind the Saracen heavy infantry. Charging into the backs of the well armored Saracens the lances of the Byzantine bodyguard made a terrific noise. Virtually the entire remaining Fatamid force turned to see a Greek banner at their backs, remorselessly churning a path into their heaviest remaining troops. It was too much. Hundreds of them threw down their swords by the Great Cross and surrendered while a very few trickled through or jumped into the river to attempt to escape.

None but a handful of mounted men would get away to carry the tale. Others would later account it a heroic victory for Stavros. For the Crusaders it was a weary mess of a victory, with their camp in ruins, supplies trampled and dmaged, dozens dead, and many more wounded needing care in enemy territory, yet ever after they would speak of that day as one of the greatest of their lives.

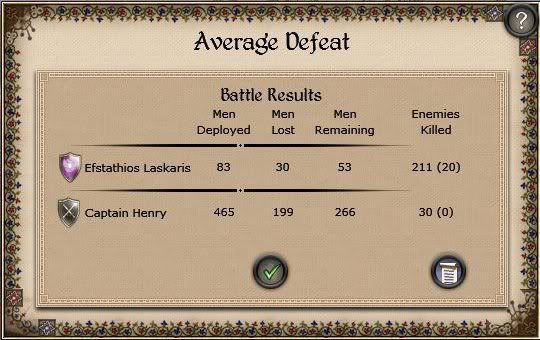

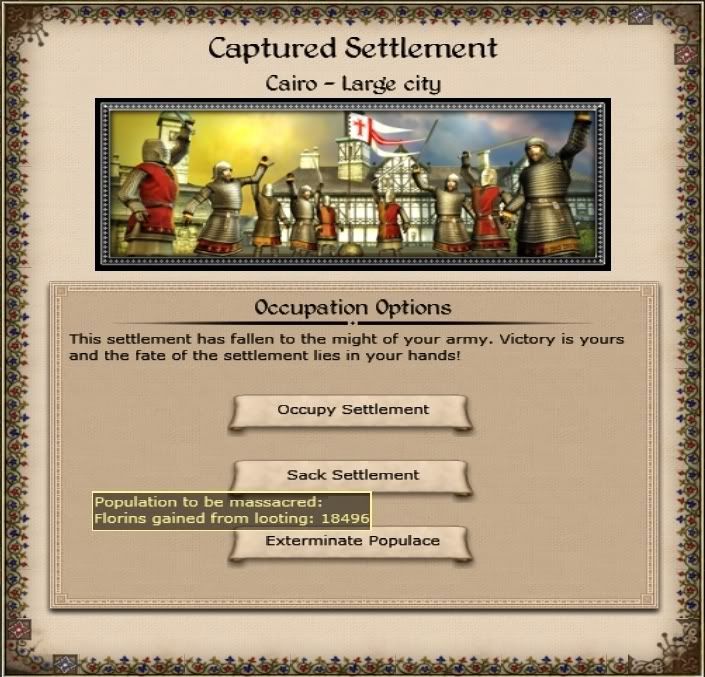

(I had no opportunity to ransom or release prisoners after this battle, so I have no idea what happened to them. If they all got added to the garrison of Cairo they may prove a formidable addition as almost all of the enemy heavy infantry 'survived' to be captured. Check out the modestly jedi kill factor for the BGs.)

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks