First Line Discussion

The Urnfield Complex and the Proto or Early Kelts

draft

Introduction

The first group of essays deals with the relationship of the Urnfield complex and the genesis of the ethnicities that would come to dominate central Europe in the first millennium BC. Among these are the Kelts, Italics, Balts, Nordics, and others. Although our goal is a discussion of the culture and ethnicity of those that occupied Greater Germany in the period covered by Europa Barbarorum, these essays offer a much needed digression. Overall, they are designed to define and examine the process of cultural emergence within the volatile crucible of the Urnfield complex.

The Concept and Chronology of the Urnfield Complex

The Middle Bronze Age Tumulus Culture was followed by the Urnfield complex, which was perhaps one of the most dynamic periods of temperate European prehistory. This complex was represented by a rather widespread common burial pattern which was associated with a number of local expressions. These include the Lusatian Culture, which is found over much of Poland, northeastern Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and northwestern Ukraine. Another expression is the Knovíz Culture of Bohemia and east central Germany. In Germany, the Urnfield complex was centered on Baden-Wuerttemberg, Bavaria, the Saarland, the Rhineland-Palatinate, Hesse, parts of North Rhine-Westphalia, and the southern portion of the Thuringia (Probst 1996).

Reinecke (1965) devised the chronological foundation for the European Bronze and Pre-Roman Iron ages, as he differentiated the Hallstatt construct as yet another localized expression, replete with it own temporal scheme, that spanned both periods. In effect, Reinecke's Bronze D and Hallstatt A and B can be equated with the Late Bronze Age and the Urnfield complex. The material assemblage of the Urnfield complex is subdivided into three discrete stages or phases. The first phase is associated with the late tumulus aspect of the Late Bronze Age, Bronze Age D, early Urnfield, and Hallstatt A1. The second phase includes the middle Urnfield and Hallstatt A2 to B1. The third phase comprises the late Urnfield and Hallstatt B2 and B3 (Probst 1996). In calendrical terms, the Urnfield complex and Late Bronze Age cover the period from approximately 1300 to 800/750 BC.

It is important to note that the Late Bronze and Pre-Roman Iron age terminus is extremely indistinct, due in large measure, to significant evidence of cultural continuity. For example, the developmental trajectory of many elements of the burial patterns, settlement forms, architectural features, and artifact designs continued uninterrupted from Hallstatt B or Late Bronze Age, into Hallstatt C of the early Pre-Roman Iron Age. With this said, it is also interesting that the transition from Late Bronze to Pre-Roman Iron age witnessed the widespread abandonment of old settlements and foundation of many new communities within particular regions.

Burial Patterns

The Urnfield complex is considered a central European phenomenon as large Late Bronze Age cremation cemeteries are typically found throughout the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland. However, this pattern of cremation burial also extended into France, Spain, Italy, Greece, the Balkans, Scandinavia, Anatolia, and the British Isles. Pertaining to the later locales, the transition from inhumation to cremation in the Late Bronze Age was noted. Yet, these areas lack the vast scale of the typical Urnfield expression, as witnessed in north central Europe.

Although cremation was intimately associated with the Urnfield complex, this method of burial had been documented in Early Bronze Age cemeteries associated with the Nagyrev and Kisapostag complexes, in Hungary. Also in the Early Bronze Age context, cremation was the dominant burial type in northern Britain. Further south in Wessex, Yorkshire, and other areas, cremation was somewhat common burial method (Harding 2000). Additionally, cremation appeared as the primary burial method at Vatya in the middle Danube basin and throughout Britain in the Middle Bronze Age.

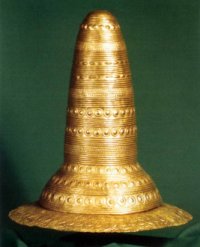

Urnfield cremations are somewhat unexceptional when compared to the richness of earlier Bronze Age burials. In general, each burial pit included one or more ceramic vessels that contained the incinerated remains of the deceased and portions of the funerary pyre. Artifacts found within the urn were those items, unaffected by the conflagration, used to ornament the deceased during the cremation rite. Typically, these included bronze pins and jewelry; as well as glass and amber beads. Additionally, the burial pits often contained the other evidence of the pyre, as well as exequial vessels, some with the trace of carbonized funerary offerings, and other metal artifacts. However, a high-status burial was excavated near Poing, in Bavaria, that included elements of a four-wheel wagon, and bronze wagon models have been found in other Urnfield cemeteries across Europe.

Excavation of the Urnfield cemetery at Očkov in Slovakia, suggest a form of public funerary rite and use of monumental architecture. Here some of the burial population was cremated on a communal pyre that also consumed many bronze and gold artifacts. Evidence of these along with numerous broken vessels and the burned ash from the pyre were covered by a six meter high mound that was stabilized by a stone retaining wall.

There is evidence that the location, of some Urnfield burials, was marked by mounds or wooden mortuary structures. At Zirc-Alsómajer, in Hungary, between 80 and 100 mounds were built over cremations, some of which were found in small limestone slab-lined pit. Returning to Kietrz, burials occasionally were centered within posthole patterns that suggest a small roofed timber-structure was built over the pit. The Urnfield burial pattern of enclosures, as indicated by a ditch, appears to have been concentrated in northwest Germany and the Netherlands. At Telgte in northwestern Germany, 35 cremations each centered within a keyhole-shaped ditch enclosure were excavated. The area within these small shallow ditches was about three to four meters in diameter with one side extended to enclose an elongated area, thus resembling a keyhole in plan (Harding 2000). These were found within a cemetery that also included burials surrounded with round and oval ditches.

As the excavations at Kietrz, in Silesia of western Poland, attest that many Urnfield cemeteries were quite large; here about 3,000 burials were recovered. The Urnfield cemetery at Zuchering-Ost, in Bavaria, is estimated to have about 1,000 burials, while Moravičany, in Moravia, has provided another 1,259 cremations (Harding 2000). Another large Urnfield population was recovered at Radzovce, in Slovakia. Here, another 1,400 burials were excavated (Kristiansen 2000). Smaller Urnfield cemeteries, such as the one excavated at Vollmarshausen and Dautmergen in Germany, provided 262 and 30 cremation burials, respectively (Harding 2000). Further afield, 40 cremation burials were recovered from a Urnfield cemetery at Afton, on the Isle of Wright, England (Sherwin 1940).

While Urnfield cremations rapidly became the dominate pattern in the Late Bronze Age, depending on the region, inhumation remained an important element of the overall burial population. For example, at Przeczyce in Silesia, 727 inhumations and 132 cremations were excavated (Harding 2000). At Grundfeld in Franconia, about half of the burial population were inhumations and half cremations (Feger and Nadler 1985; Ullrich 2005).

Over 10,000 Urnfield or Late Bronze Age cremation and inhumation burials have been excavation to date. However, this may represent only an extremely small fraction of the overall potential sample population. Additionally, several hundred Urnfield cemeteries have been investigated. Yet again, it is probable that many thousands more have been destroyed by cultivation and other recent development.

References Cited

Feger, R. and M. Nadler 1985

Beobachtungen zur urnenfelderzeitlichen Frauentracht. Vorbericht zur Ausgrabung 1983-84 in Grundfeld, Ldkr. Lichtenfels Oberfranken.

Harding, A.F. 2000

European Societies in the Bronze Age, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kristiansen, K. 2000

Europe before History (New Studies in Archaeology, Cambridge University Press.

Probst, E. 1999

Deutschland in der Bronzezeit, Bertelsmann, München.

Reinecke, P. 1965

Mainzer Aufsätze zur Chronologie der Bronze- und Eisenzeit, Habelt.

Sherwin, G. 1940

Letter in Proceedings of the Isle of Wight Natural History and Archaeology Society 3, 236.

Ullrich, M. 2005

Das urnenfelderzeitliche Gräberfeld von Grundfeld/Reundorf, Lkr. Lichtenfels, Oberfranken, Materialhefte zur Bayrischen Vorgeschichte, Reihe B, Band 86.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks