Very nice AAR, I especially like the history-style approach and the pics with the "EB font". If I may ask, why is the first chapter entitled "Chapter II" and the second one "Chapter IV"?

Very nice AAR, I especially like the history-style approach and the pics with the "EB font". If I may ask, why is the first chapter entitled "Chapter II" and the second one "Chapter IV"?

Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer: The Gameroom

Well, Chapters I and III told of the events prior to the beginning of this AAR. Chapter I told the story of Hellenism in the East. And Chapter III told the story of Seleukos Nikator himself. Now that we're caught up with the House of Seleukos, we'll chronicle each King's reign henceforth...

Read The House of Seleukos: The History of the Arche Seleukeia

for an in-depth and fascinating history of the heirs of Seleukos Nikator.

CHAPTER V

Antiochos II (Theos)

263 to 230

It was Antiochos II, now a young man of twenty-eight, who took up the Seleukid inheritance in 263 BCE. In him, the grandson of Seleukos Nikator and Demetrios Poliocertes, the martial spirit of his Makedonian ancestors ran strong, if not quite yet pronounced. To many in his kingdom and beyond, he was still the reprobate heir who had spent a dissolute and dissipated youth in Seleukeia indulging every excess known.

What they did not know, was that the young man was profoundly affected by the death of his grandmother Apame, when he was twenty years old. Seemingly overnight, he had abandoned his indulgent ways and sought to make himself a better man, expressing a keen interest in politics. Availing himself of the finest teachers in his father’s kingdom, he proved to have a keen intellect. Impressed by his son’s talents, Antiochos I appears to have named him co-regent around the time of his Galatian campaign. Even in this position, Antiochos II had trouble living down his wanton youth and was subject to much gossip by the scandal-mongers.

The death of his father threw the kingdom in disarray. The old king had only recently fought in battle and had seemed in good health. Plans were already in place for a campaign to stifle the ambition of Pergamon. Such plans would have to wait. Antiochos was now faced with new and more pressing concerns.

In the East, his uncle Achaios and his line were struggling to stave off incursions from the Parni, a nomadic tribe from the Central-Asian steppe. What had first been minor raids into Seleukid lands had now turned into something far more troublesome. The nomads appear to have gathered support and had overthrown Seleukid rule in Astauene and Hyrkania. Their leader, Arshâk, was so bold as to declare himself a king.

These cavalrymen hailing from the steppes of Central Asia formed the backbone of Parthian armies the Seleukids faced

However, the more immediate threat to his kingdom was the Seleukid’s old foe, the Ptolemies. And the threat was directed at the heart of the Seleukid realm, Antiocheia.

The Seleukid empire at the time of Antiochos II’s accession in 263 BCE.

The Seleukid empire at the time of Antiochos II’s accession in 263 BCE.

§1. The Second Syrian War (263 – 254 BCE)

No sooner than the young king had laid his father to rest, the armies of Ptolemy II marched into Antiocheia and besieged the Seleukid capital. Clearly Ptolemy II had seized this brief moment of transition within the House of Seleukos to try to claim all of Syria as his own. Perhaps encouraged by his generals and emboldened by his alliance with the growing power of Rome, Ptolemy II believed himself strong enough to gain the upper hand in the Ptolemaic-Seleukid conflict. Perhaps he still thought of the young king as the dissipated boy at his father’s court.

Ptolemy II Philadelphos (285-258 B.C.)

Whatever the case, the armies of Ptolemy the son of Ptolemy poured forth into Syria. No man of war himself (his interests were intellectual and artistic and he was clearly of a more sensual nature), the attack was instead led by one of his generals, Dexikrates Kanopoios, of whom little is known.

Ptolemy II’s action, by all accounts, took the young king by surprise as the bulk of his army was still stationed with him in Galatia. Antiocheia itself was protected only by a small garrison led by his younger brother, Sarpedon. However, in stark contrast to the Ptolemy, Antiochus II was possessed of the same fibre as the tough old Makedonian chiefs. With nary time to grieve, he immediately marched his army on a tough journey from Ankyra to Syria where he met up with reinforcements led by the governor of Edessa, Pythiades Lydikos.

A bureaucrat unaccustomed to war, Pythiades was so taken by his campaign with the young king that he kept a detailed diary, parts of which survived to this day. Of particular interest is his account on the numbers and composition of the army. Antiochos’ army consisted of 15,000 phalangitai, 2000 peltastai, 3000 mercenary Greek hoplitai, 1,000 elite hetaroi, as well as a contingent of 600 prodromoi (lesser nobility fighting as light cavalry). For his part, Pythiades was able to raise 3000 archers from the nearby Caucasus, 1,500 heavy Persian archers, and 1,500 Babylonian spearmen. This army was to finally arrive outside the besieged city to find the army of Ptolemy attacking the walls.

a. The First Siege of Antioch

The jewel of Syria, Antiocheia, had held out for the better part of a year. Word had reached the city that the young king was coming to its defense, so the people remained hopeful despite privations endured. When news arrived that the young king had crossed the Orontes and was now within a day’s march from the city, hope rose even further. However such news was met by the Ptolemaic army with an immediate decision to attack.

Though Sarpedon was only able to commit around 8,000 garrison soldiers, the city’s real defense were its seemingly impregnable walls. Though now lost to the sands of time, these awesome stone walls stood as testament to Seleukid might and power in the region. Against them Dexikrates threw 10,000 of his own phalangitai, 7,000 levies, including a contingent of Jewish soldiers, 8,500 akontistai, 1,000 toxotai, and 1,600 Galatian soldiers who had settled in Egypt and were renowned for their ferocity in battle.

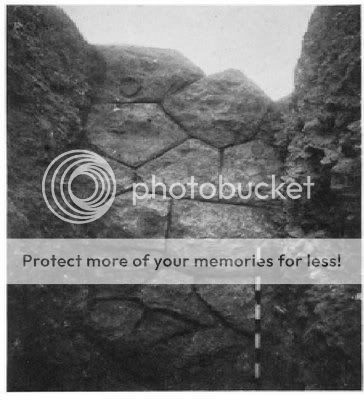

The Princeton excavations conducted in the 1930s uncovered one patch of Seleucid era walls on the slopes of Mt Staurin.

The Princeton excavations conducted in the 1930s uncovered one patch of Seleucid era walls on the slopes of Mt Staurin.

Knowing they could not bring down the walls before Antiochos’ reinforcments arrived, the Ptolemaic army hoped to use ladders and towers recently finished to take the walls. Sarpedon’s plan, such as it was, was to fend off the attackers long enough for his brother to arrive with reinforcements. Pythiades account informs us that the battle commenced mid-day on a clear day.

What it must have been like on the walls under the mid-day sun amongst the carnage and metal we can only imagine. The fighting on the walls was fierce and brutal and had raged for hours by the time Antiochos’s reinforcements arrived. Sarpedon’s men suffered heavy casualties that day. Of his 8,000 men, only 3,000 were to return home. But they more than succeeded in buying time for Antiochos’ army to arrive. They bore the brunt of the attack and yet were responsible for the Seleukid victory that day. Against their 3,000 losses, Sarpedon’s men dealt a staggering number of casualties, nearly 22,000. Pythiades notes that there was surprisingly little left for Antiochos’ army to accomplish, “The king arrived expecting to find his brother dead instead he arrived to find him a saviour.”

The fierce and brutal fighting on the walls raged for hours.

Sarpedon Soter rallying his men at the First Siege of Antioch.

Sarpedon had indeed exemplified Makedonian bravery that day, rallying his men from the front as the Ptolemaic soldiers burst through the gates and leading a perilous charge through city streets against the Galatians. His efforts were such that he too was given the appellation Soter. Antiochos reportedly bore no jealousy at this, himself having said to have remarked in his later years, “My father and brother saviours both and I only a god.”

Sarpedon Soter leading a desparate charge against the Galatians.

To commemorate the victory, Sarpedon commissioned a giant bronze statute of Tykhe, the Greek goddess of fortune. The statute depicted Tykhe seated upon the back of a swimming man, the god of the Orontes River. She wore a turret crown, representing the defensive walls of a city, and holds a sheaf of wheat. The original is lost to us and all that remains is a Roman copy at the Musei Vaticani in Vatican City

Tyche of Antioch. Reduced Roman copy of colossal Greek bronze statue by Eutychides ca 260 BC.

Last edited by socal_infidel; 08-14-2008 at 02:50.

Read The House of Seleukos: The History of the Arche Seleukeia

for an in-depth and fascinating history of the heirs of Seleukos Nikator.

Great update, socal infidel! Keep it up!

Maion

~Maion

CHAPTER II

Antiochos II Theos

...

a. The Syrian Offensive (262 – 258 BCE)

After the disaster at Antiocheia, the forces of Ptolemy were left in disarray. Ptolemy’s next most capable general, Protarchos Philopator, was in Marmarike poised to seize Kyrenaia from Magas. Instead, he was ordered to Coele-Syria to defend against retribution by Antiochos II. The survivors from Antiocheia were themselves dispersed. A number of Galatians and pezhetaroi were able to seek refuge in Sidon, while a larger number of the pezhetaroi made way to Posidium, where they hoped to escape by sea to Tarsos.

With all of Coele-Syria now virtually undefended, Antiochos seized the initiative to add these lands to his own. The bulk of his army largely intact after Antiocheia, Antiochos and Pythiades quickly struck southward. The pezhetaroi who were camping outside of Posidium awaiting the Ptolemaic fleet were dispatched with first, struck down to a man. Antiochos now made his way into the heart of Ptolemaic Coele-Syria.

1. The Siege of Sidon

Within a few months of Antiocheia (262 BCE), Antiochos was outside the gates of the great Phoenician city, Sidon. His engineers went to work and the city was laid siege. After winter passed, the city was attacked. We know from Pythiades’ account that the siege was a particularly bloody one. Though greatly outnumbered, the resistance led by the experienced Galatians and pezhetaroi was fierce and it was not until Antiochos committed his own kleruchoi to the attack that the siege was won.

Perhaps remembering their fate at the hands of Alexander some seventy years before, the city of Tyre quickly recognized Antiochos as their new master without a fight. Although the two great centers of Phoenicia were in Seleukid hands, Ptolemy’s armies were still nearby. To the north of Sidon, Alexandros Thraikikos was seeking to rendezvous with 7,500 phalangitai, 1,600 peltastai, 1,600 thureophoroi and 1,600 thorakitai who were camped just outside Tyre. A force consisting of mostly levies and conscripts from Ioudaia was also making its way towards Damaskos. Meanwhile, Protarchos Philopator and his large army were nearing the Nile and were making their way to Ioudaia.

2. The Battle of Mt. Hermon

Though likely an intentional effort by the Ptolemies to allow Alexandros Thraikikos to merge with his force outside Tyre and to buy time for Protarchos’ army, Antiochos had no choice but to meet the force converging upon Damaskos. The city was largely ungarrisoned and would likely fall to Ptolemy. At the foot of Mt. Hermon, just north of Panion, battled was engaged. The Ptolemaic force was able to gain the high ground and awaited the Seleukid approach. Despite the advantage in terrain, the army itself was no match for the Seleukid forces. Consisting of mostly levies and conscripts from Ioudaia, they could not compare with Antiochos’ battle-hardened professional soldiers. Of the 13,000 men, only 1,000 survived; with over half cut down by Antiochos’ hetaroi and prodomoi as they flanked the force and charged from above.

Antiochos leading the charge of the hetaroi at the Battle of Mt. Hermon

3. The Battle of Tyre

In the fall of 261, Antiochos and his men arrived outside Tyre. Alexandros Thraikikos and his men had been denied sanctuary in the city and had no choice but to commit to battle. Although of higher-quality than the force Antiochos dispatched at Mt. Hermon, Alexandros’ men were largely new recruits and had little battle experience. Alexandros made one last effort at convincing Tyre to allow his men inside city walls but was again denied. He arrived back at camp to find Antiochos’ men and his own men drawn up in battle formation.

After unsuccessfully pleading for entry to Tyre, Alexandros Thraikikos arrived back at camp to find his men engaging the Seleukid phalanx

While the main battle lines advanced, Antiochos and his cavalry, as well as a contingent of Jewish soldiers sought out Alexandros’ own cavalry force. Alexandros’ cavalry were quickly chased from the field, Alexandros himself fleeing for his own life. The main battle lines now engaged, the Ptolemaic forces could not bear the brunt on the Seleukid onslaught. The Seleukid phalangitai simply outmatched the Ptolemaic troops. Returning to the main line, Antiochos found the surviving Ptolemaic forces in panicked flight. The survivors fled south where they were able to meet up with the Ptolemaic navy, who still controlled the seas.

Alexandros and his cavalry were routed from the field. Upon seeing their general take flight, the Ptolemaic soldiers followed suit

4. The Phoenician Revolt

In perhaps the most surprising turn of events in Antiochos’ Syrian campaign, a small Phoenician army led by a certain Osca set out from Orthosia in 261 and by 260 was at the gates of Sidon. Osca was likely counting on support from the city, but Pythiades, who had been left in charge there by Antiochos, had done his best to win over the natives to the Seleukid cause. Pythiades himself was unable to convince Osca of the foolishness of his cause. Instead Osca set out north ostensibly to drum up support for Phoenician independence in Tripolis.

Osca never reached Tripolis, Antiochos had no choice but to confront this force. The armies met on the field of battle on the beaches south of Berytus along the road leading to Tripolis. The small Phoenician army was thoroughly annihilated by Antiochos’ forces. The movement had died before it even began.

5. Battle of Gindarus

Afforded little time to rest, in the fall of 260, Antiochos was greeted with word that Antiocheia had again come under siege. By all accounts, Alexandros Thraikikos, who had survived the Battle of Tyre, had fled by sea to Tarsos. There he mustered a small force to add to his own survivors from Tyre. This force of 9,000, if their plan was to divert Antiochos and allow time for Protarchos, was successful in that sense.

Among the 9,000 Ptolemaic troops at Gindarus were 600 of their elite phalanx units, the Klerouchikon Agema

Though boasting a number of veterans from earlier Ptolemaic campaigns in Asia Minor, most all units were severely depleted and fighting at half-strength. When faced with the arrival of Antiochos, Alexandros fled north crossing the Orontes. Antiochos’s men caught up with him in the forests south of the small village of Gindarus.

The forests south of Gindarus were not perfect conditions for the Seleukid phalanx, but the Ptolemaic forces faced the same conditions. The size of the Seleukid army and the leadership of Antiochos proved decisive.

Bolstered by his earlier successes, Antiochos proved a fearless leader at Gindarus, once again leading the charge from the front.

The battle was notable in that both Alexandros and the satrap of Kilikia, Olympiodoros Kilikiou were struck down, as were nearly all 9,000 of Alexandros’s men. More importantly, all of Kilikia, Pamphylia and Karia was now left open for the Seleukids. Word had also reached Antiochos that Protarchos had reached Rhinocorura near the Ioudaia border. Antiochos charged his brother Sarpedon with the taks of taking southern Anatolia, while word was sent to Pythiades at Sidon to muster whatever reinforcements he could. The king was marching south to confront Protarchos' army and to take Ioudaia for the Seleukids.

...

Last edited by socal_infidel; 08-12-2008 at 21:48.

Read The House of Seleukos: The History of the Arche Seleukeia

for an in-depth and fascinating history of the heirs of Seleukos Nikator.

Very nice.

I shouldn't have to live in a world where all the good points are horrible ones.

Is he hurt? Everybody asks that. Nobody ever says, 'What a mess! I hope the doctor is not emotionally harmed by having to deal with it.'

CHAPTER V

Antiochos II Theos

263 to 230

...

6. Battle of Gazara

The view of present-day Gazara from the south. The Battle of Gazara was fought just north of here along an arid stretch of road leading to the town.

After Gindarus, Antiochos made his way down the Syrian coast, while Sarpedon made preparations for his campaign against the Ptolemies in Southern Anatolia. By summer of 259 BCE, Antiochos was just north of Gazara. The town was strategically situated at the junction of the coastal highway and the highway connecting it with Jerusalem through the valley of Ajalon.

Tracking Antiochos’ movements along the coast, the Ptolemies were able to land an army from Crete just north of Dora. Reinforcements from Hierosolyma arrived from the east, and the three armies met on an arid stretch of plains along the road to Gazara. The Ptolemaic forces were small in comparison to Antiochos’ forces, numbering 17,000 to Antiochos’s 38,000. But amongst the Ptolemaic forces, were 7,500 klerouchoi, 3,200 thureophoroi, 1,600 Galatians, and 4,000 Jewish soldiers.

The Ptolemaic and Seleukid phalangitai engaged in battle. At Gazara, the Ptolemaic phalanx again proved it was no match against Seleukid might.

The Ptolemaic army could not overcome their lack of cavalry at Gazara. Once again Antiochos’ own cavalry proved overpowering, with the king leading, as always, the charge from the front. It was after Gazara that the first whispers of Antiochos’ divine status were murmured. Not only had he not yet lost a battle, he had thrown himself fearlessly into the fray in every engagement and had emerged unscathed. But his toughest battle lied ahead.

The Seleukid auxiliaries celebrate their victory at Gazara. After the battle, the first whispers that Antiochos was divine were heard.

...

Last edited by socal_infidel; 08-14-2008 at 02:51.

Read The House of Seleukos: The History of the Arche Seleukeia

for an in-depth and fascinating history of the heirs of Seleukos Nikator.

you should post this in the AAR of the month thread!

https://forums.totalwar.org/vb/showthread.php?t=106019

Mini-mod pack for EB 1.2 for Alexander and RTWSpoken languages:

(just download it and apply to get tons of changes!) last update: 18/12/08 here

ALEXANDER EB promoter

Truly a great AAR -- More!

We want more please. :(

Truly excellent!

This is where my signature is.

Is this AAR still alive? I have to say its awesome!! Actually I planned to do an AAR about Arche Seleukeia too, once my current AAR is finished. I planned to do some history-styled AAR as well and now I have to admit: I must cancel my plan because I wouldnt be able to live up to your example ;)

I hope you will continue this... and I hope I will get another good idea for my second AAR.. :D

Men create the gods in their own image. (Xenophanes)

Do not concern yourself with my origin, my race, or my ancestry. Seek my record in the pits, and then make your wager. (Arcanis)

Finished campaigns:

RTW Seleucid Empire

The Exile - Basileion Kydonias AAR

Thanks for the kind words. I still have a ton of .tgas on an external drive around here somewhere. I may revive it, but to be honest, I undertook this AAR during a self-imposed lull from modding. I have been beyond busy lately with PRO DEO ET REGE and The Last Kingdom. But I do regret not finishing this AAR. Maybe I'll get back to it when things die down.

Read The House of Seleukos: The History of the Arche Seleukeia

for an in-depth and fascinating history of the heirs of Seleukos Nikator.

Bookmarks