The Kingdom of Naples

On 27 June 1458, Afonso V of Aragon died. His illegitimate son, Ferrante, inherited the Neapolitan throne and the Kingdom was independent again for the first time in nearly 2 decades. Ferrante I was a strong King, skilled in most areas of governance.

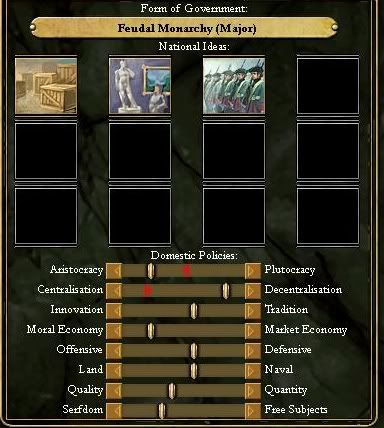

Yet, as he surveyed his Kingdom, there was relatively little to be proud of. Naples controlled all of southern Italy, but the land and the peoples were much poorer than their northern cousins. The cities were smaller, less developed, and there were no universities to speak of. Despite its size, Naples was not a great power, indeed it was poor and without friends. Naples specialized in Shrewd Commerce Practices, the king was a Patron of the Arts, and the nation had enacted Military Drill. These policies were all useful, but they were disorganized and did not clearly indicate a path to more advanced ideas.

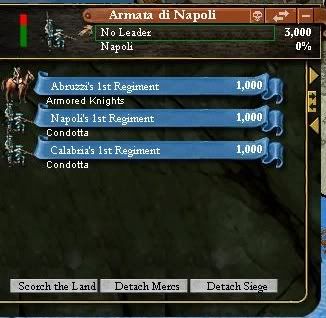

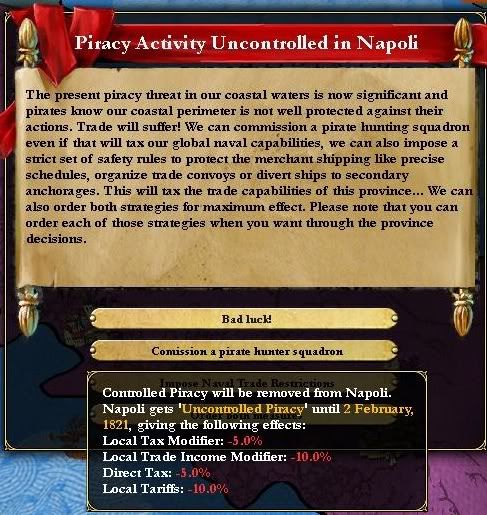

Naples had a massive coastline, making it supremely vulnerable to pirate raids, but it had no naval tradition to speak of, not even a single anchorage. Her navy was decent, but assembling a larger force would be difficult. The army was almost non-existent.

The single most significant aspect of the world, as far as Ferrante I was concerned, was the Aragonese possession of Sicily and Malta. Naples retained strong claims on these lands, and re-uniting them with the Kingdom was an absolute necessity if Naples ever hoped to be able to exert influence in the northern Italian lands. Yet, there was no obvious way to regain those lands. Aragon remained strong, with an alliance to Portugal. Even Castille guaranteed Aragon's independence, making an aggressive war against Aragon suicidal.

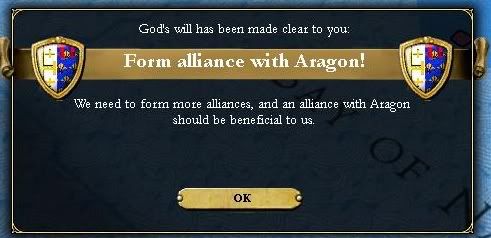

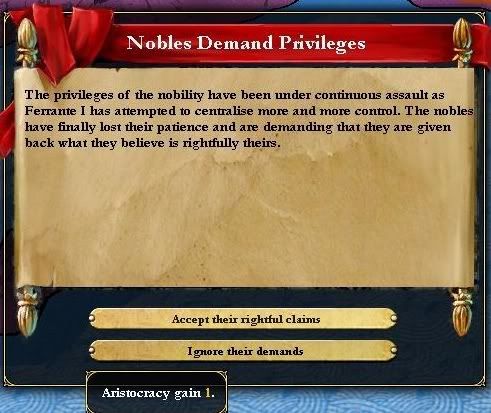

So, Ferrante I decided to bide his time. He would invest in the economy of his Kingdom and do all he could to make it stronger... all the while waiting for Aragon to make a mistake. The local nobles felt that Ferrante I should form an alliance with Aragon, but he laughed at such a notion and simply ignored it.

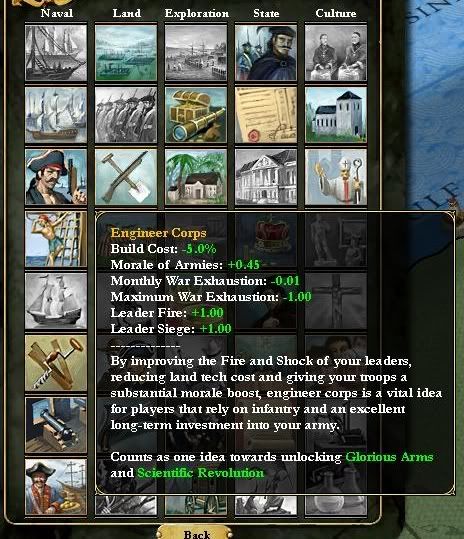

Ferrante immediately doubled the size of the Royal Army, keeping a standing force of 6,000 men. This was sufficient to suppress any rebellions that would occur as well as to deal with wars against minor Italian powers. Within a year or so, Ferrante I had sufficiently improved the government to add a new focus to his policies. After great deliberation, he chose to create Engineer Corps.

This was not an ideal choice, for it did not benefit the economy, or alleviate the naval weakness of the nation. However, such a policy meshed well with Patron of the Arts and Military Drill, allowing his successors to freely pursue the more advanced scientific and military ideas, if they so desired. In this way, Ferrante I sacrificed short-term interests for the long-term good of his nation.

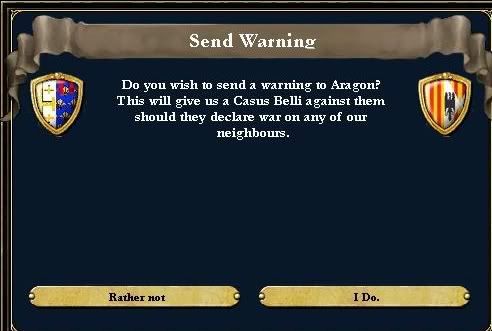

On the diplomatic front, an alliance with Tuscany was formed, and a formal warning was sent to Aragon. Should the Aragonese ever engage in aggressive warfare, Naples would be well-placed to regain Sicily and Malta.

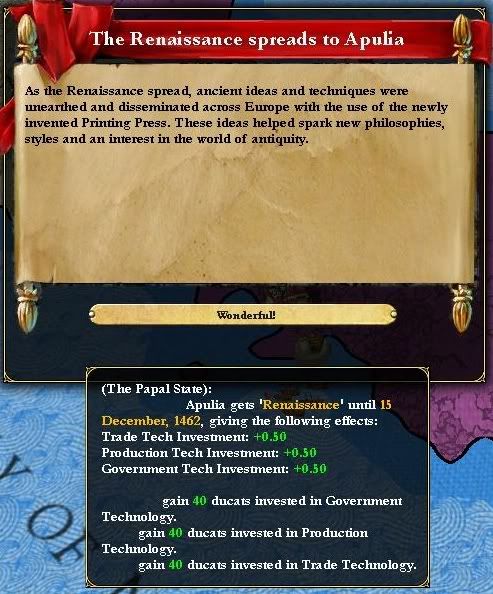

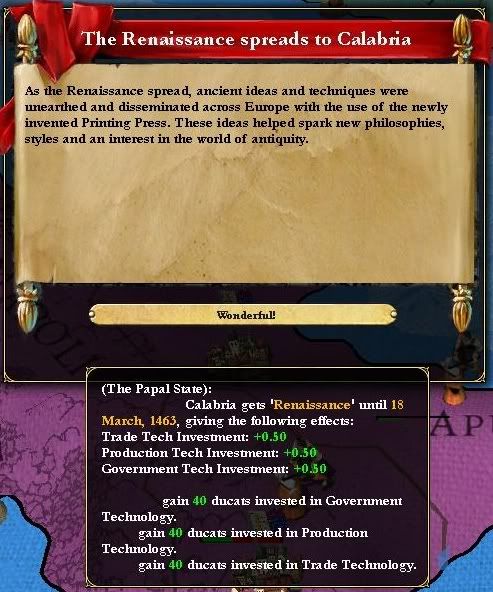

As Ferrante turned his attention to domestic improvements, there was both welcome and unwelcome news. On the positive side, the Renaissance was finally reaching southern Italy...

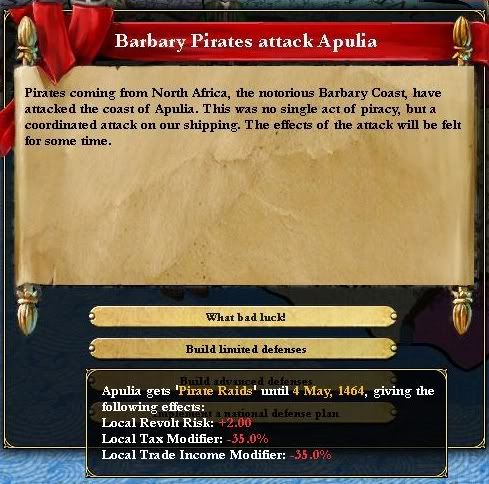

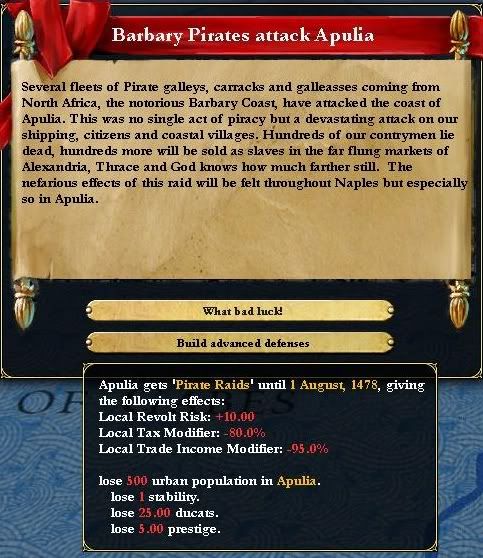

...but the piracy that Naples was ill-positioned to control finally showed itself.

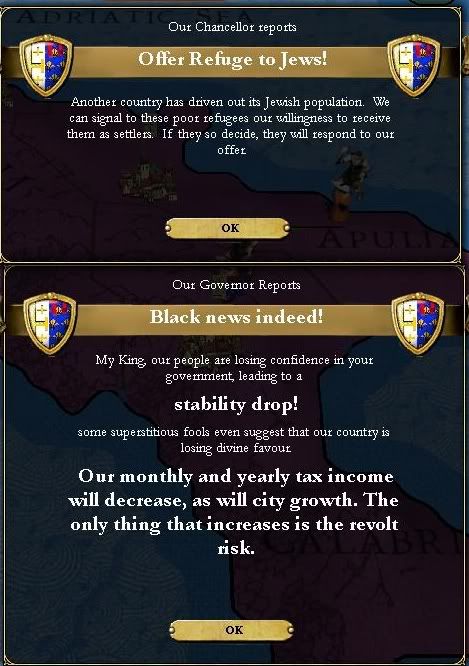

It was not long before news arrived that foreign nations were expelling their Jews. With congregations of Jews in several Neapolitan cities already, Ferrante I decided to offer them refuge in Naples. He believed the economic benefits they would bring in the long-run out-weighed the unrest their presence would cause.

The affairs of Europe outside Italy bothered Naples relatively little during the reign of Ferrante I, but there was one notable exception in 1460. Provence declared independence from France.

This was significant, as the ruling house of that nation held strong claims to all Neopolitan lands. While they were a weak nation, they would have to be watched in case they ever decided to try and exercise those claims. That prospect could not be ignored, as even the Neopolitan nobles were acting uppity and demanding privileges.

By the end of 1462, Ferrante I had finished his economic reforms. This had begun with re-directing the nation's policies to favor the market economy. Without any local centers of trade, and with no prospects of gaining one any time soon, Neopolitan traders would be in foreign markets. Thus, the benefits of a moral economy would be wasted on them.

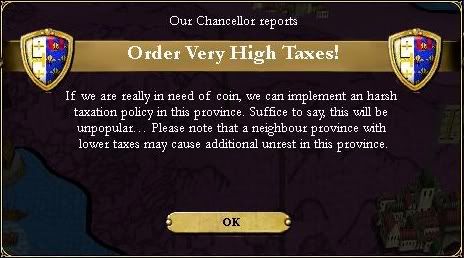

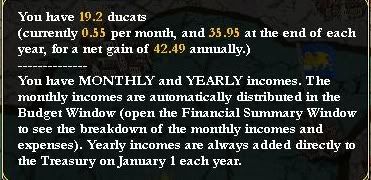

Ferrante I then established a strong Neapolitan trade presence in Venice, raised taxes to Very High levels in all provinces, and decided to begin minting coinage at a rate that would increase inflation by 0.1% per year. Such a level of minting would greatly aid the treasury, without crippling the nation by high inflation in future years. The result of these reforms was a surplus income of over 40 ducats per year. This money was badly needed for economic investment and piracy defenses.

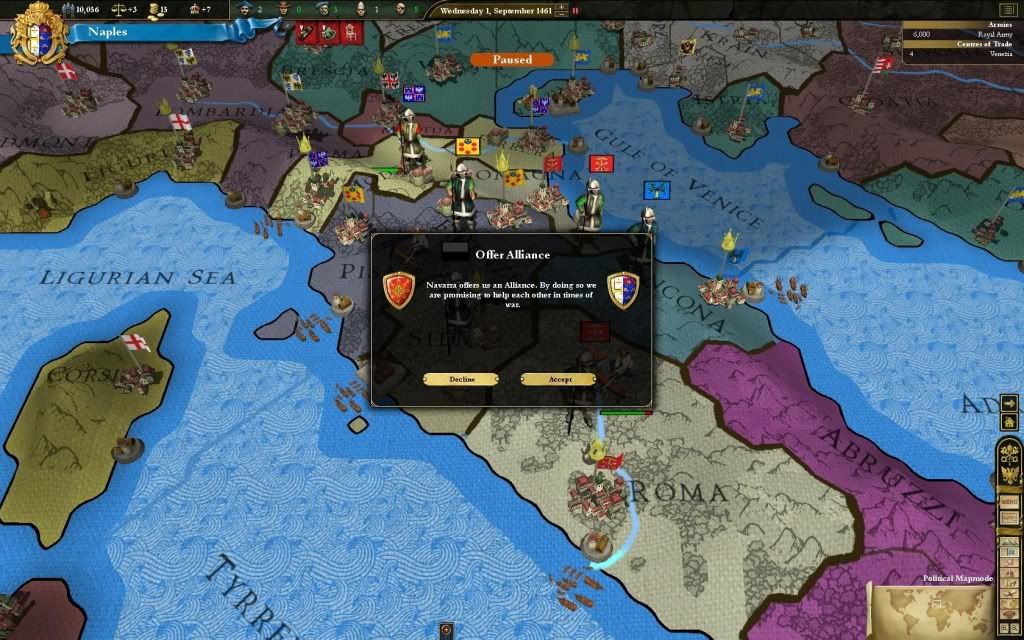

Around this time, Navarre offered an alliance to the King. Ferrante I laughed the Navarrese diplomats out of his court. Such an alliance could offer nothing to Naples but trouble. Yet the Navarrese were nothing if not persistent. They returned 5 more times with the same offer throughout Ferrante I's reign, all of which were similarly rebuffed.

In 1463, the Pope made war on Urbino, in an attempt to unite his Italian possessions.

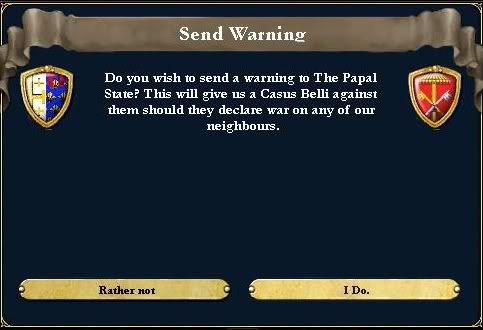

Ferrante I cursed himself for not having warned the Pope against such a move, as this would have been the perfect moment to attempt to capture Rome itself. The northern Italian nations united against the Pope and he was inevitably defeated. Urbino actually gained Romagna in the subsequent peace treaty, though it was later returned to the Pope through diplomatic means. Ferrante I warned both the Pope and the Urbinese against future aggression, purely to give Naples an excuse to annex their lands in such an eventuality.

Shortly thereafter, Ferrante I at last convinced the Venetians to agree to an alliance. He had attempted to make such an agreement for over a year, but the Doge had been very stubborn. With the Venetian and Tuscan alliances, Naples had strong allies to aid it in Italian affairs. A trade agreement was also made, to reduce the risk to Neapolitan merchants in Venice itself.

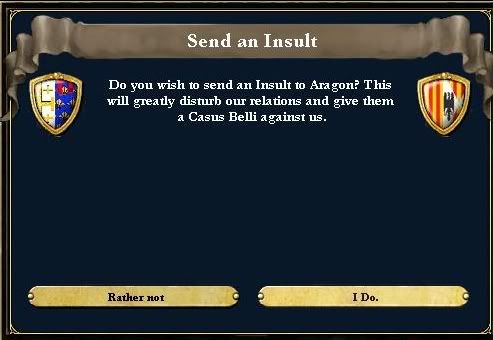

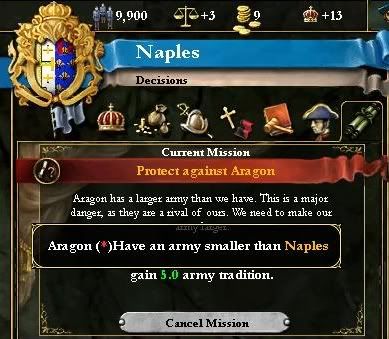

With the position in Italy strengthened, Ferrante I turned his attention back to Aragon. Ferrante dispatched his flatulent cousin to the Aragonese court, where his actions were inevitably seen as an insult. The nobles were also asked to re-think their mission of an alliance, and they responded with a far more sensible mission.

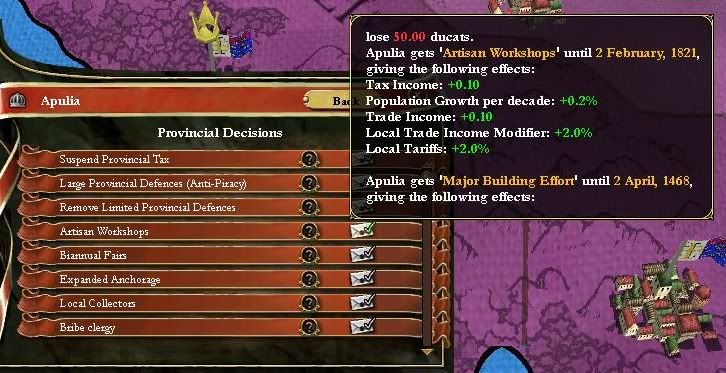

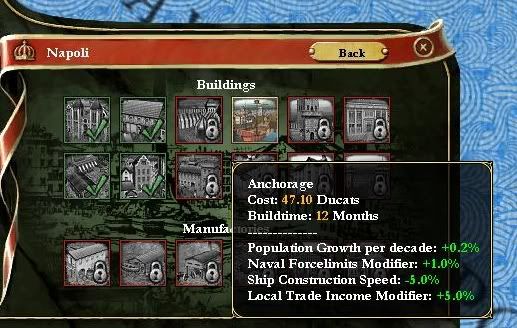

With relations now sufficiently low, war with Aragon was not likely to cause much instability. All the while Naples was slowly growing stronger. The income generated by Ferrante's economic reforms was re-invested in the country. Artisan Workshops were built in every province, an Anchorage was constructed in Naples, and a Provincial Accountant was constructed in Calabria.

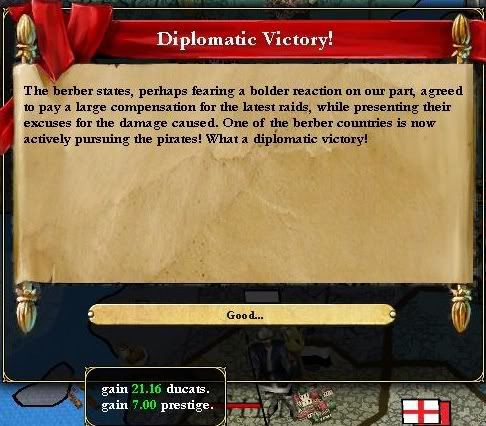

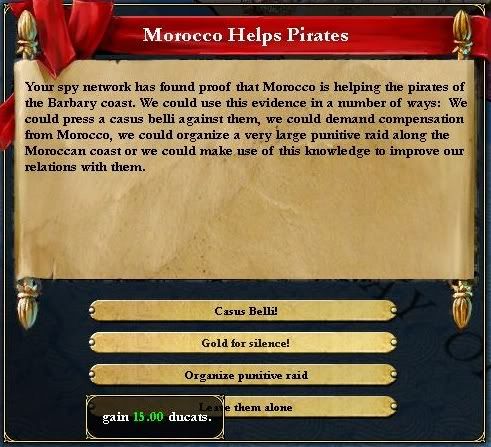

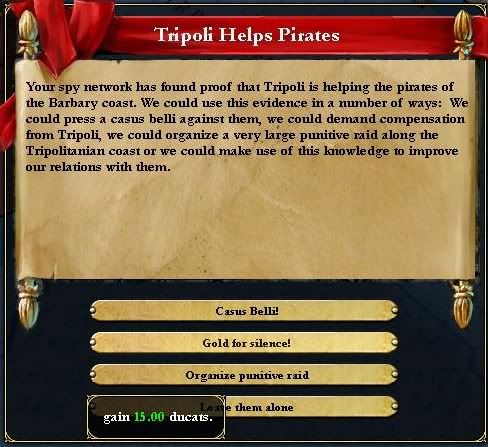

In addition, attention was devoted to combating piracy. Limited Provincial Defenses were organized in all provinces, and a Limited National Defense Plan was enacted throughout the entire Kingdom. While this worked relatively well to combat local piracy, the Barbary Pirates themselves were harder to contain. They raided Neapolitan provinces every few years, but aggressive diplomatic action by the King resulted in cash payments by the Barbary states that went a long way towards making up for the damage done.

As the years went by, Ferrante I began to get restless about the lack of any progress in securing further lands in Italy. Naples needed to expand in order to grow stronger, and with the economy looking up, he decided to attempt it diplomatically instead of militarily. A royal marriage and and alliance was arranged with Urbino, with the hopes of convincing that small nation to become a vassal.

Unfortunately, while those offers were accepted, vassalage was apparently an impossible dream. Ferrante I did not even bother having his diplomats ask. In 1472, Venice declared war on Mantua.

Naples was called upon to uphold their alliance with the aggressor, but Ferrante I balked at such an idea. Venice had no other allies except Naples, and they faced an alliance of nearly all of northern Italy as well as the Holy Roman Emperor, Austria. Defeat was inevitable in such a war, so Ferrante I abandoned the Venetians to their fate. The damage to Neapolitan prestige was nothing in comparison to the economic consequences such a war would have had. After 2 years of war, Venice eventually managed to buy its way out of war without losing territory, despite having nearly their entire nation occupied. Ferrante I smiled to himself for wisely avoiding that war.

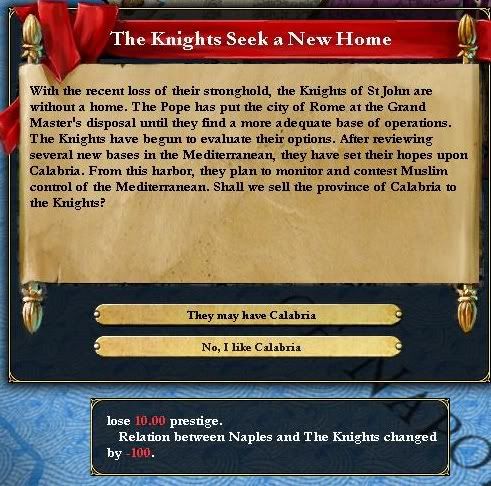

In September 1472, the Knights of St. John appeared in the King's court. The island of Rhodes had recently fallen to the Ottomans, and they were seeking a new home for their order. They requested that Ferrante I give up Calabria to aid them. The King nearly had the men executed for their impertinence; such an idea was so insulting was almost worth of a declaration of war... had the Knights had any lands on which to declare war. Instead, he simply sent them packing with a severe tongue lashing. Little did Ferrante I know that the Knights of St. John would eventally play a crucial role in Neopolitan affairs...

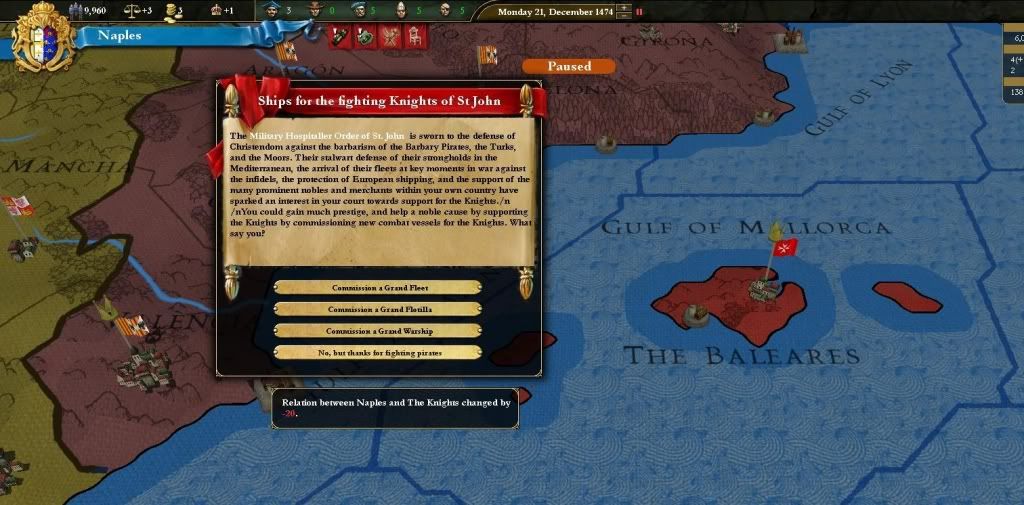

Two years later, another diplomatic envoy from the Knights appeared. This time they were requesting ships to aid them against the Barbary States. Apparently the King of Aragon had donated the Baleares Islands to their cause. Ferrante I was pleased with the news, as it was one less province from which the inevitable enemy could draw resources. Still, Ferrante I was not pleased enough to pay the sums the Knights were requesting. They left empty-handed once again.

In 1476, the Barbary Pirates attacked Apulia for the third time in as many years. The raid was devastating, and it hit just as Ferrante had invested in the Provincial Accountant in Calabria. The damage done by this raid forced Naples to take out a loan. This angered Ferrante I greatly, as he prided himself on having stable finances, but at least it would be an easy loan to pay back, given the reliable yearly income.

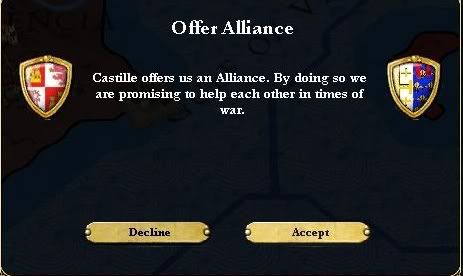

Ferrante's anger was sated by the arrival two weeks later, of a diplomatic delegation from the King of Castille. Apparently the King was a friend of Naples, and wished to sign a military alliance. Ferrante I tried to suppress his glee, as this was a huge diplomatic coup that could be used against the Aragonese in a future war.

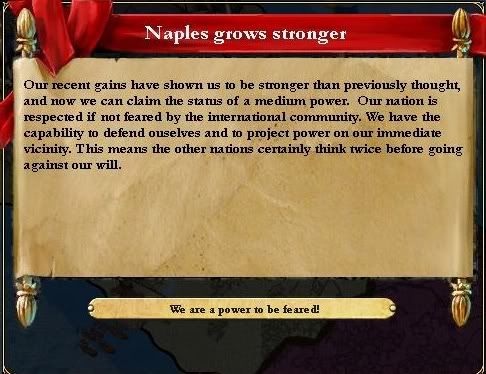

The rest of the diplomatic world took note of this alliance, as it clearly indicated that Naples was no longer a minor power..

In March 1480, the Knights arrived in Ferrante I's court for the third time. As they were being 'escorted' out of the court, they managed to scream something about a war with Aragon. Ferrante I allowed them to return, and quizzed them about this in detail. The King of Aragon, it seemed, had declared war on the Knights, having thought twice about his decision to give up his islands to the Order.

This was a major development, and Ferrante I considered it carefully. Naples had warned Aragon against aggressive warfare, and this was a valid causus belli without the risk of social unheval. In addition, all of Aragon's allies had abandoned them for such a dishonorable act against the noble crusading Order. At the same time, Malta had no other friends to speak of. If Ferrante I agreed to intervene, it would be a direct war between Aragon and Naples; the Knights could no be expected to provide much in the way of assistance. After some restless nights of indecision, Ferrante I send a diplomatic envoy to the King of Aragon to inform him that a state of war existed between the two nations. There might not be a second opportunity to remove the Aragonese from Sicily and Malta, and Ferrante I did not mean to miss this one.

He immediately assumed personal command of the army, and ordered the recruitment of 3 more regiments to bring the Royal Army up to 9,000 men. The treasury was stuffed with money ready to pay off the loan which was about to come due. Ferrante I decided that the bankers could wait; the money was needed by Naples now.

The Aragonese did not wait for the Neapolitans to assemble their new regiments, and they immediately invaded across the Straits of Messina. Ferrante I decided not to wait for the new regiments, and marched to the relief of Calabria. The battle was great victory, and the Aragonese were routed with heavy losses.

Unfortunately, Ferrante I had underestimated Aragonese naval power, and the Neapolitan navy was blockaded by a powerful fleet and was unable to prevent the defeated Aragonese army from escaping back to Sicily. Even more unfortunately, Ferrante I had suffered a minor wound at the Battle of Calabria. While it was not immediately life-threatening, an infection set in that no amount of leeching would cure. On September 17, 1480, Ferrante I, King of Naples, died. His son, the unimpressive Giovanni I, inherited a Kingdom at war.

In his last will and testament, Ferrante I gave some advice to his successor:

My son, I regret that I leave to you this war that I have prepared for all my life. It is crucial that we are victorious. Sicily and Malta must be regained if we ever hope to have the power to deal with the rest of the Italian states, particularly those that are members of the Empire. Yet, this is a difficult war. The Royal Army is strong, and with competent leadership can defeat anything the Aragonese send against us. However, we are in dire peril at sea. We cannot cross to Sicily without defeating the Aragonese navy, and they outnumber us by a large margin. Fortunately, they are divided by the blockade of our coastline and their fleets might be defeated individually if speed and luck is with us. Perhaps taking out further loans to finance the construction of more galleys might be prudent, before making our move at sea.

While the blockade hurts us the longer it goes on, time may still be our friend in this war. The Aragonese King has greatly angered his people with this war against a fellow Catholic, without a causes belli. His country is completely destabilized and this is wrecking havoc at home. His losses in the siege of the Knights on the Baleares and against our own army at Calabria have raised Aragonese war exhaustion high. If we can hold on long enough, rebellions may begin in their home provinces. Hold on, my son, and have faith. With some skill and luck, you will be the man who regains our rightful control over Sicily and Malta!

Save Game File

Originally Posted by Leon Blum - For All Mankind

Bookmarks